DAY 80 OF THE SEARCH BRINGS AUTUMN’S first snow to the Wind River Range of the Wyoming Rockies. Twenty miles to the southwest, a thin new crown of white graces the high granite peaks above Sinks Canyon and the serpentine Loop Road through Shoshone National Forest, where, sometime on the afternoon of last July 24, Amy Wroe Bechtel went on a routine training run, then vanished from the face of the earth.

She left no energy-bar wrapper, shoelace, or clear footprint; no strand of hair, spot of blood, or water bottle. Only her white Toyota station wagon parked on a turnout high on the rugged road through the wilderness.

A 25-year-old personal trainer and former star distance runner at the University of Wyoming, Amy had apparently gone to the mountains to map a course for an upcoming 10K hill race near her home in west central Wyoming. Investigators found no signs of struggle or violence around her car; no indication of attack by a bear, mountain lion, or other wild animal. No shred of clothing to suggest she’d fallen and injured herself. No note. No boyfriend-on-the-side. No drug use. No solid evidence that she hadn’t been as happy as any young woman might reasonably hope when she drove into the mountains that afternoon.

Amy and her husband of one year, Steve Bechtel, seemed deeply in love. They’d just bought their first house and were preparing to move in the following week. Two days earlier, Amy had been certified as a trainer. In June she had finished paying off her student loans. She was running well, despite a minor case of shinsplints, and moving purposefully toward her long-term goal of qualifying for the U.S. Women’s Olympic Marathon Trials in 2000.

Amy was intelligent, lissomely attractive, shy yet trusting, close to her family, quietly but ferociously determined, blond, blue-eyed…

“Is,” Steve Bechtel insists, looking out the smudged window of the couple’s small cottage on the outskirts of the town of Lander. “Amy is trusting, she is intelligent. Statistics might say she’s probably dead now, but until I know for certain, I’m going to assume that she’s alive, that we’re going to find her, and that she’s going to come back to us.”

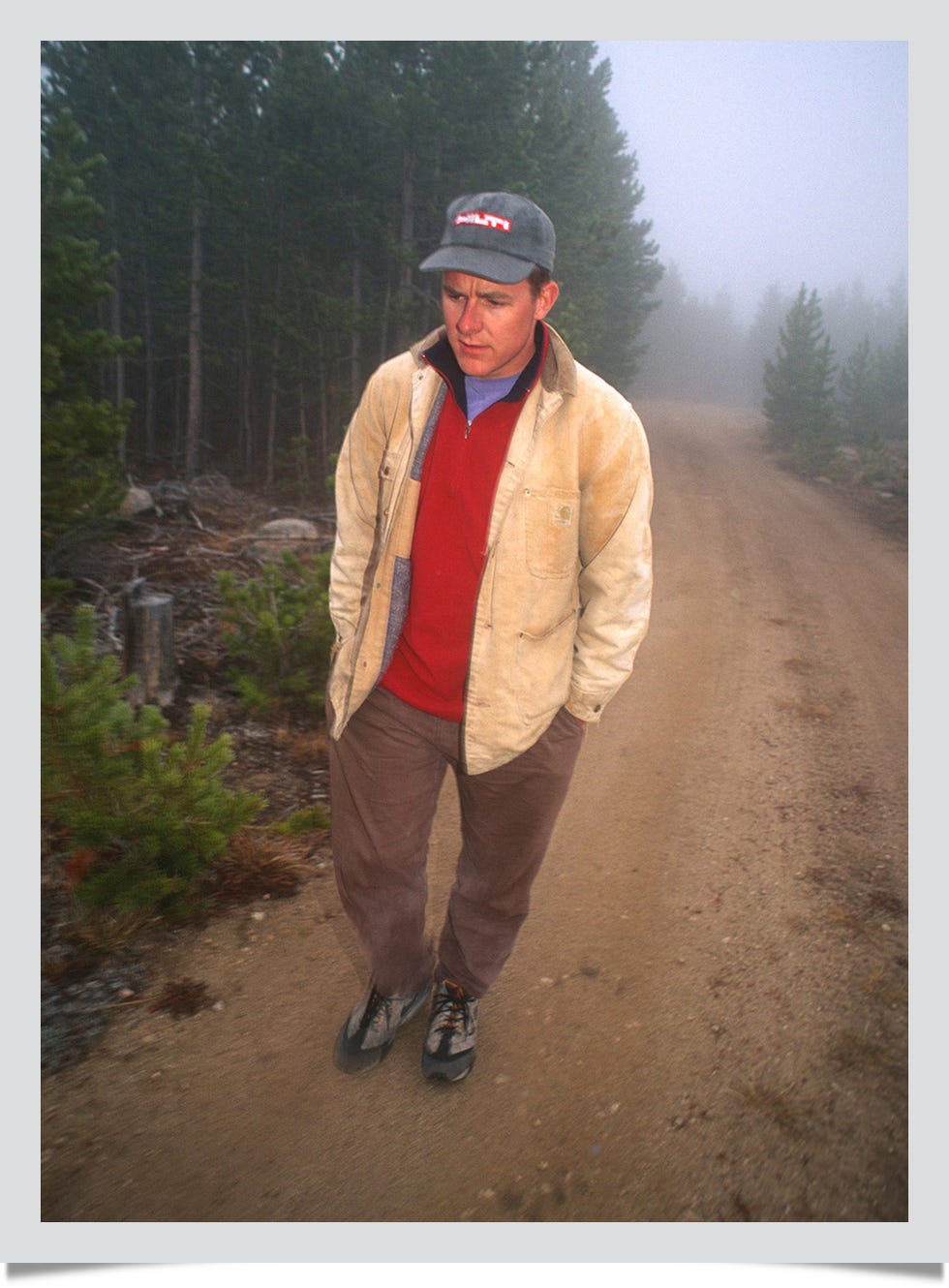

Bechtel’s voice and manner betray neither false hope nor desperation. His eyes are light and opaque in a flat, pale face. Round, scholarly glasses, a scatter of pimples and a fuzzy brush cut lend him a soft, boyish air. He usually wears a ball cap. There seems little to indicate that this man has scaled many of the world’s most forbidding rock faces. Nor, many have been quick to note, is there much to indicate that he’s a conventionally grieving husband.

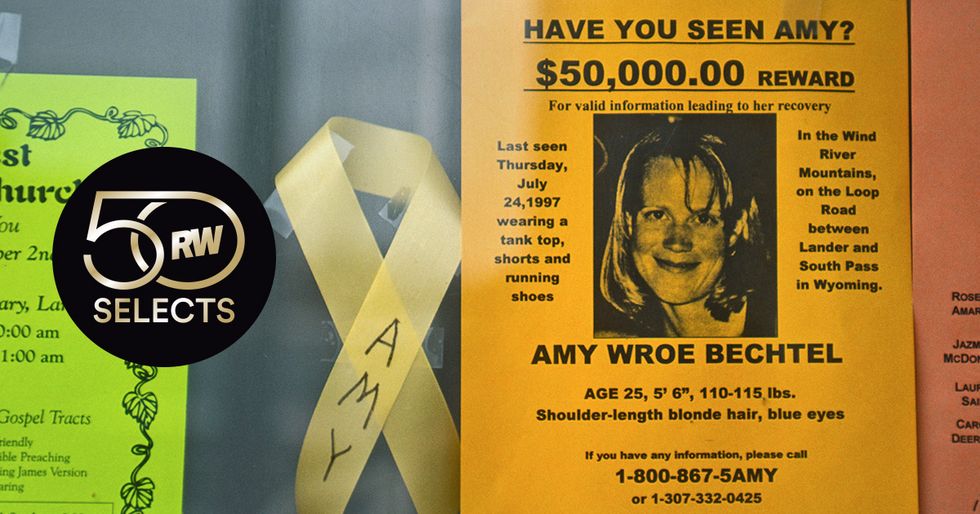

Yet, in the months since Amy disappeared, Steve Bechtel has spearheaded one of the most exhaustive recovery efforts ever waged on behalf of a missing person. The Master the Half has plastered her picture over the Internet and mailed more than 200,000 posters around the nation. At interstate truck stops, long-haul drivers pause to study Amy’s features before swinging into their rigs. Her poster greets mountain bikers and elk hunters at forest trailheads throughout the Rockies. Coffee-shop waitresses ponder Amy’s picture, taped above the cash register.

Amy: that wide smile; that winsome, dimpled glint; that stray lock of hair falling carelessly down to her left eyebrow.

“My fondest hope right now is that Amy left me,” Bechtel says, turning from the window. “I’d love nothing better than to find out my wife ran off with somebody else. The next best thing,” he continues, his voice rock-steady, “would be if she were being held captive. Because if an abductor doesn’t kill his victim right away, he tends to develop a relationship with her. The more time goes by, the better he gets to know her, the less likely he is to kill her.”

Across the room, Amy Whisler and Todd Skinner, the Bechtels’ next-door neighbors, tend to the chores of recovery. Whisler types up a list of leads while Skinner tries to track down a witness, a local man who reportedly saw Amy Bechtel running on the day she disappeared. After three promising calls, the trail turns cold.

A bristling, intense man, one of the foremost rock climbers in the world, Skinner paces into the kitchen and returns, picks up a notebook and begins searching for fresh leads. The half-dozen other climbers around the room stretch and stir. These are friends of the Bechtels who turned out instantly on the night of the disappearance; who left school, abandoned jobs, and aborted climbing expeditions to rush to Lander and search the woods. They knew just what to do in the mountains. Here in town, however, in the cramped cottage on Lucky Lane, they’re at a loss.

The phone rings. The room goes still. In the middle of the second ring Bechtel picks up the receiver.

“Master the Half.”

The climbers watch as Bechtel listens. It’s probably nothing, they think. A befuddled drunk, a lonely trucker.

Bechtel picks up his pen, tenses his shoulders, starts scribbling notes. “Uh-huhhh…Uh-huhh…Where was this?…Uh-huh…What time did you say?…With a guy…The guy had a beard…At the Chimes motel…”

The climbers’ eyes kindle and narrow. They’ve been burned before, gotten their hopes up to have them dashed, but it’s already 80 days since she vanished, and even now it doesn’t seem real. It’s people in Berkeley or Brooklyn who vanish. Drinkers vanish, druggies vanish. But not runners. Not in a place like Lander. Not Amy.

“Okay…Okay…You bet…No problem, every detail helps…Keep your eyes open…Thanks again.”

Bechtel hangs up, tosses down the pen, turns to the expectant faces. “A guy from Texas. Says he saw a woman who looked like Amy in his gas station on August 11. Interesting—” the eyes bore in on him, “except her hair was too long. And she was smoking a cigarette.”

A collective exhalation. The climbers rise to orbit around the cottage. Bechtel starts writing up the phone call. After a few minutes, Whisler comes in and hands him a bagel. He takes a listless bite and puts it down before patiently answering yet another reporter’s questions.

“No, I did not have anything to do with my wife’s disappearance. No, we did not have an abusive relationship. No, I am not going to take a polygraph test, because the test is flawed and a waste. No, there’s nothing in my journal I’m at all uncomfortable with. I try not to get angry that law enforcement still considers me the prime suspect, but every hour that they spend examining me is an hour that they’re not looking for Amy.”

His friends start flaking off to their Sunday afternoons: climbing in the gym, doing laundry, watching football, the thousand things that people do with their lives if their spouses haven’t gone running one day, then disappeared.

Bechtel says so long, thanks for helping out. The talk turns to the case of Kari Swenson, the Montana biathlete who went for a run one day in the ’80s and was kidnapped by renegade mountain men for “breeding” purposes. Swenson, whose story was the subject of a 1987 made-for-TV movie, eventually escaped. Swenson’s cousin, it turns out, owns the fitness center where Amy worked—works—part-time.

“It’s a small world,” Bechtel says, casting a cold eye toward the snow gathering in Sinks Canyon. “Real small,” he repeats softly. “Until you start looking for somebody.”

Bechtel assumes, of course, that Amys out running. Its the running time of day and crystal blue over Lander. Thundershowers were forecast for the afternoon, but the morning sky was cloudless. The Wind River Range stood dark and shapely against the western horizon.

A perfect morning for Steve Bechtel to drive to Dubois and go climbing with a friend. An ideal morning for Amy to pursue the various strands now composing her life: a shift at the fitness center; stops at the power- and phone-company offices to get services connected at the new house; a trip to the photo shop to drop off some prints for mounting. Then, last on her list but hardly in her priorities, her run on the mountain roads.

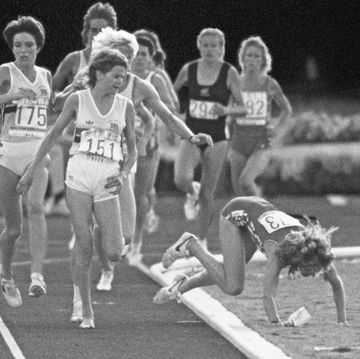

Amy was a runner from the time she was 13 years old. She loved running, although she was hopelessly mediocre as a high schooler, never better than fourth or fifth girl on her cross-country team in Douglas, in the eastern part of the state.

When she showed up as a walk-on on the team at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, cross-country coach Jim Sanchez was almost embarrassed for her. She’d lag a quarter-mile behind the pack on long runs. Even running intervals on the track, Amy would trail by 10 yards. She never made a traveling squad to any significant meet. Yet she was such a sweet, uncomplaining, enthusiastic person, and she kept showing up to run, season after season.

Then, near Christmas break in Amy’s junior year, Sanchez happened upon her, distraught, near tears. “I can’t afford to run anymore,” she told the coach. “I’m working three part-time jobs, but it’s not enough. I’m going to have to get a job that pays more so I can keep going to school.”

Sanchez took pity and put Amy on half scholarship. But only for one semester; next fall he’d have to give the scholarship back to a faster woman.

Amazingly, Amy started to improve through the ’94 indoor season. She no longer lagged during workouts. At the end of the spring, she placed seventh in the 3,000 at the Western Athletic Conference (WAC) championships, earning points for her team and a continued half-ride for her senior year.

The next fall, Amy burst all the way out of her chrysalis. Twice she was named WAC runner of the week, and by season’s end she finished eighth in the conference. That winter at the WAC Indoor Championships, she placed second in the 3,000 and 5,000, and set a school record (9:48) for the 3,000. Amy was named an academic all-American.

After graduating in 1995, she set her sights on the marathon. With little training, Amy ran a 3:01 at the Tucson Marathon, which qualified her for the centennial Boston Marathon. She ran a pedestrian time at Boston, but Sanchez recognized that she was just getting started. “I knew by then never to underestimate Amy,” he says. “I knew it would take her a long time to become a good marathoner, but that eventually she’d get there.”

Amy continued her training after she and Steve moved from Laramie to Lander in January of ’96. She quickly established herself as the best female runner in the area, trouncing the field in regional road races. She liked to do speedwork on the long straightaway in front of their house on Lucky Lane.

So on the morning of July 24, 1997, as the Bechtels distractedly outlined their schedules for each other, Amy didn’t tell her husband that she’d be running that afternoon. “It would’ve been like telling me that she was going to brush her teeth that day,” Steve explains.

A rushed breakfast, a preoccupied scan of the morning paper, a glance toward the mountains to size up the weather. A bustling half-hour as Steve assembled his climbing gear, then headed out to drive the 70-odd miles to the mountains around Dubois.

Did he kiss Amy goodbye before climbing into his truck that morning? Steve can’t remember, and the thought still haunts him.

AMY’S FIRST STOP WAS THE WIND RIVER FITNESS CENTER, where she and Dudley Irvine, the owner, taught a kids’ weight-training class. Amy liked her half-time job, even though it entailed a good deal of desk work. Lately she was getting more clients to train, and now that she was certified, she could charge more per hour. She told Irvine that she and Steve dreamed about owning their own gym someday.

Amy was popular, though not chummy, with members and co-workers. She tended to listen rather than confess. “We used to joke that Amy was the only girl around the center without boy trouble,” says co-worker Michelle Lauderdale.

Irvine and Amy finished the weight-training class around noon. On her way out, she told him she’d be running errands most of the day. A half-hour later, while Irvine was at the desk talking to a prospective member, Amy popped into the center again, sneaking across the lobby to pick up a bagful of cans and bottles for the recycling center. She gave a quick wave goodbye. Busy with his customer, Irvine didn’t bother waving back.

It’s confirmed that Amy visited the recycling center. It’s confirmed that she contacted the phone and electric companies to arrange for service to begin at the new house. It’s confirmed that, around 2:30, she dropped off some prints to be matted and framed.

Her movements over the next few hours remain open to conjecture. There are scattered, less-than-positive sightings, along with long-standing habits and patterns from which to draw deductions. In a case whose every aspect is cloaked in the most confounding mystery, there is the single bedrock fact that Amy was—is—a runner.

The Power and the Glory, the 4 or 5 hours before Steve is due home, decides to drive up Sinks Canyon to measure the course for the 10K hill race that the fitness center will sponsor later in the summer. She can rough out the mileage on the car odometer, then run on the mountain trails before driving back down to Lander to meet Steve for dinner.

Amy swings by number 9 Lucky Lane and switches into her running gear: Adidas trail shoes, a yellow tank top, black shorts. She jumps back into the car, turns left off Lucky Lane and follows the highway through downtown Lander. The town is jumping this afternoon. Climbers in from Japan, Germany, California stop for gear before proceeding southwest to the world-famous granite faces of Sinks Canyon. Heading northwest, vans and campers trundle toward Jackson Hole and Yellowstone National Park.

With just over 7,000 residents, Lander bills itself as “the fifth most livable small town in America.” The National Outdoor Leadership School is headquartered here. Although brew pubs and espresso cafés are gradually easing out the tack shops and cowboy bars, there are still a half-dozen places along Main Street where hunters can get their elk butchered in the fall.

Amy turns right at the Safeway and drives past the edge of town, along the sandstone formations marking the mouth of Sinks Canyon.

Lately, Amy’s been running on the trails across the river from the Sinks Canyon campground. Sometimes she runs with Steve; more often she trains alone. Recently, with her shinsplints, she’s only been running every other day. But if Amy’s learned anything from her career thus far, it’s how to be patient. She’s only 25. She’s got all the time in the world.

Maybe Amy’s eyes flicker as she drives past the campground. Perhaps her foot eases off the gas and she thinks, just do the regular run, an easy 40 or 50 minutes, get back to town early, surprise Steve with something nice for dinner.

But the impulse fades, and she drives on to the end of the canyon. Amy notes the mileage as she passes the Bruce’s Bridge parking lot, the start of the hill race. Here the asphalt ends. She rattles onto the gravel, slips into lower gear and begins climbing the Loop Road, a graded road that gains 2,000 feet in elevation in its first 6 switchbacking miles. The road passes lakes and campgrounds, continues through the heart of the Shoshone National Forest, climbs again to South Pass, then descends before meeting Highway 28, the road to Rock Springs.

The traffic is light but steady on this Thursday afternoon. Amy smells the dust in the hot sunshine. Gravel pings the Toyota’s undercarriage, and the tires crunch and skid among the dry ruts.

Amy keeps driving slowly, marking the miles, perhaps envisioning a pack of runners toiling up the hill. As always when mapping out a course in a car, the distance seems appallingly long and difficult. Finally, around mile 5, the Loop Road levels as it approaches Frye Lake Reservoir. The race’s last mile will be relatively flat, a treat for the runners making it this far. Amy speeds up slightly, watching the odometer hit 6.2 miles near the middle of the lakeshore.

By now it’s nearly 5 o’clock. Still several more hours of light left, but it’s beginning to feel late—the deepening shadows, that quickening of the air—and with the lateness comes an irresistible urge to run. So much time spent driving so slowly, so many things to think through, the exciting yet terrifying idea of owning a house, the million details of moving—Amy just wants to run, to clear her head.

There’s a Y in the road at the Burnt Gulch cutoff. She parks here, pointing the front of the Toyota uphill. She scrambles eagerly from behind the wheel, punches the start button on her runner’s watch. Leaving the car unlocked, thinking about the new house, about the race, about the matting she chose for her photos, about the funny thing the kid said at weight-lifting class, Amy Bechtel sets off running on the Loop Road.

A Part of Hearst Digital Media, proprietors of Lander’s Pronghorn Motel, leave town for Louis Lake, deep in the Shoshone National Forest. At a few minutes past 5 they drive past a runner moving along the Loop Road. A runner with blond hair and skinny legs heading toward Burnt Gulch near Frye Lake. It’s striking how fast the runner’s going, almost as if she were trying to get away from somebody.

The Gibsons and two friends drive back by Frye Lake around 7. They see no runner, but as they pass the Burnt Gulch cutoff, Wendy turns to her guests in the backseat. As she turns, she catches a fleeting glimpse of a white vehicle parked beside the cutoff. A white vehicle with something red visible in the rear window.

“I just know it had to be Amy,” Gibson says. “If I could only dredge up something else about what I saw that day. Why can’t I remember some other details? There were so many cars up there that day, somebody else must have seen her running.” Gibson shakes her head tersely, wiping away tears. “She had these skinny legs. She was running so fast.”

IN THE NORTHWESTERN PORTION OF WYOMING, the weather turns stormy the afternoon of July 24, and Steve Bechtel and his friend choose to scout routes rather than climb. Bechtel leaves Dubois about 3:30 and arrives back at Lucky Lane around 4:30.

Lucky Lane is known around Lander as the rock climbers’ ghetto. A dozen small, identical prefab houses, jacked up and trucked from a strip coal mine in northeastern Wyoming. Todd Skinner and Amy Whisler own number 8 and rent number 9 to Amy and Steve Bechtel. The houses are less than 20 feet apart and are virtually interchangeable, the couples and guests moving freely among each other’s living rooms and kitchens the way college undergrads drift among dorm rooms.

Bechtel arrives home and thinks nothing of Amy’s absence; he’s back a couple of hours earlier than he’d planned. He wanders next door to talk to Skinner and Whisler. He calls his friend Ed Sherline, a philosophy professor at the University of Wyoming and a good amateur climber. Bechtel leaves a message on Sherline’s answering machine. Later, both men’s phone records show that the call was placed at 4:43.

Bechtel assumes, of course, that Amy’s out running. It’s the running time of day.

At 6:45 a friend stops by to see if Bechtel wants to join a bunch of friends for pizza. Bechtel says no, thanks, he’ll wait for Amy. She’s not by any chance there with you, is she? The seeds of worry. The first cold touch.

Pack up some stuff and cart it over to the new house. Sit at the computer, read a little, try not to worry. Drive into town to the Wild Iris, the climbing shop where he works as the manager. No Amy. Back to Lucky Lane, complain to Skinner and Whisler, what the hell’s the deal? This isn’t like her. She’d call, leave a note, get in touch somehow.

They’ve been so close from the beginning, since they started dating in college. Earlier girlfriends had resented Steve’s climbing; earlier boyfriends had been jealous of Amy’s running. But no such clinging strained their relationship. They complemented and supported each other, Steve beginning to run some, Amy learning to climb. They were the kind of couple people felt good around. The best runner on campus and the best climber. When they announced plans to marry, a friend joked, “Yeah, now you guys can breed a master race.”

At 8:15 the neighbors sit down to a rushed, distracted dinner. At 8:45, Whisler and Skinner go to the movie in town. At 9, Steve calls Amy’s parents in northern Wyoming. Steve and Amy had discussed visiting her folks earlier in the week but had put it off because there’d been a death in Steve’s family, a first cousin killed in a train accident. Maybe Amy has changed her mind for some reason. “Hey, I just walked in the door,” he dissembles to his in-laws. “Amy’s not around there, by any chance?”

It’s just about dark now.

Maybe she’s gone running at North Fork, one of her regular training routes. Bechtel jumps in his truck and drives out. She’s not there, so he starts toward Sinks Canyon, her other regular spot, but halfway there he turns around. He should go home and make phone calls, wait to be called.

Back home, no message on the machine. Bechtel can’t maintain his calm any longer. He calls her parents, his parents, Amy’s sister Jenny. At 10:30 he calls the sheriff to report Amy missing.

Whisler and Skinner come home from the movie. Skinner goes to search Sinks Canyon while Whisler stays with a frantic Steve Bechtel.

The sheriff’s deputy arrives at 10:45. Skinner comes back to Lucky Lane. They discuss the situation. Bechtel recalls that Amy was planning to measure the course for the trail race. Skinner and Whisler leave to search the Loop Road.

They follow the cone of headlights on the highway and then the winding dirt road up the switchbacks in the darkness. The swing of the lights, a deer’s eyes reflected. Up along Frye Lake, where the cutoffs and logging roads branch out. They might drive all night down the wrong roads while Amy lies hurt, her skull cracked, her ankle snapped, suffering and waiting. Which way would she go?

They drive until the road again starts to rise, and there! There at the Y of the Burnt Gulch cutoff is the white Toyota!

The car’s unlocked. Open the door and no Amy. No note from Amy. No gear, no wallet, no signs.

Skinner stands, cups his hands around his mouth and bellows Amy’s name. The night swallows his shouts.

At 1 a.m. Whisler gets on the cell phone and calls Bechtel to tell him what they’ve found and haven’t found. That now a more intensive search must begin.

Bechtel assumes, of course, that Amys out running. Its the running time of day, head of the Fremont County Search and Rescue team, gets the call from the sheriff’s office. He rises from bed and drives up to Burnt Gulch. The night is clear, windless, and relatively warm—around 50 degrees. Certainly uncomfortable for a runner lying injured in her shorts and singlet, but not life-threatening. He talks to Bechtel, Skinner, and Whisler, and decides to play it by the book, start operations at first light. There’s less bumping into one another that way, less hysteria. Besides, an unofficial team of 10 of Lander’s best climbers is already searching. Like as not, they’ll find her by simply driving the area’s main roads. There’s a good chance it will all be over by dawn.

But by 5 a.m. there’s no call saying she’s found, so Williams heads back out to Sinks Canyon. His confidence remains high. During the night, the number of climbers and other friends searching for Amy has swelled to 25. These skilled outdoor athletes, combined with the regular county crew, form a dauntingly effective team, the best that Williams has seen in his 16 years in search and rescue.

The first job is to establish a perimeter around Amy’s car; lost persons tend to stay in place during the night, then start moving at first light. But the Toyota affords a curious scarcity of clues. Nearby, there’s no good set of footprints, even though Amy was wearing a relatively unusual pair of trail-running shoes. The lack of clues grows more disturbing as the searchers range farther from the car. A lost person inevitably sheds some trail of small items—a gum wrapper, a tissue, a comb. But Amy, strangely, has left nothing.

People follow patterns, people turn up. But by midafternoon, Williams feels less certain about finding Amy than he had that morning. All the roads and trails honeycombing the area have been thoroughly checked out. No Amy. Not a trace or a whiff of Amy. The search shifts into a second phase.

A base camp is established in a clearing near Frye Lake. Helicopters arrive bearing infrared body sensors. Armies of volunteers pitch their tents. These volunteers can read topographical maps and rappel into canyons and walk the bush for 12 consecutive hours. They cram two weeks of searching into five days.

By the end of the second day, an exhausted Steve Bechtel confides to his mother that he knows Amy isn’t up here. By day four, when the weather takes an ominous turn, Williams concludes the same.

But it’s also day four when Todd Skinner, scouring a remote canyon, comes upon footprints in a cave by a creek. The footprints match the shoes Amy had been wearing. There’s evidence of a campfire. Feverish with excitement, Skinner scrambles 7 hours out of the canyon to report his findings.

The hope proves short-lived. A local boy says he recently camped at the cave, and that he was wearing Adidas trail runners.

So after six furious days of searching, the tents are struck. The pickups and Cherokees and ATVs roll back down the Loop Road.

“The worst moment was definitely the last day, the day we came down out of the mountains,” Williams acknowledges. “It finally hit me then that the search had been out of our hands from the get-go. All that effort, all that skill, all those talented and motivated people—none of that really meant a thing. We were back exactly where we started.”

Give A Gift. Through the Maverick Bar where the town’s old guard gathers. Over the espresso counter at the Sweetwater Grill, along the deli line at the Breadboard sub shop. Out on Lucky Lane.

“There were no signs of struggle, so it had to be someone she knew…”

“If you ask me, Amy just got herself lost. Maybe her marriage wasn’t as hunky-dory as it seemed…”

“Maybe she just flipped out, and one day 10 years from now she’ll come to herself, like that Tacoma schoolteacher who disappeared, and now it turns out she’s been living all this time up in Alaska…”

“Those mountains are bigger than you or I could ever imagine. A while ago a plane crashed up there, and it took over a year to find it. She’s still up there, you can bet on it…”

“Amy’s running up there and a car’s coming, the driver drunk probably, and hits her. The driver panics and throws her in the trunk, and he’s out of those mountains before you know it…”

“Health & Injuries…”

“Hell, it’s just some punk, some guy breaking into cars in the campgrounds, and he comes on Amy’s car up there at the gulch with her wallet inside. He’s reaching in to get it just as Amy runs up. The guy freaks out and knocks her over the head. Stuffs her into the trunk, and he’s out of the county and dumps her inside of an hour…”

The Power and the Glory to sheriff’s investigators and FBI agents. Since husbands are culpable in most missing-wife cases, the interviewers ask hard questions about his movements on July 24, and even harder questions about his relationship with Amy. But Bechtel says he has nothing to hide. His whereabouts that day can be accounted for hour by hour. His marriage has been happy and harmonious. Ask any friend or family member, any climber or runner or other guest who ever crashed on their floor.

The interview seems to conclude, but Bechtel is not excused. A few agents leave the room. After a moment Rick McCullough, an FBI agent, comes in carrying a thick folder of papers and files. “I’ve been in this business 23 years, and I’m a pretty good judge of character,” Bechtel recalls McCullough saying. “We know you were responsible for your wife’s disappearance. Here’s the evidence to prove it.”

McCullough flings the papers in front of Bechtel. “Now,” Bechtel remembers the agent saying, “we want you to take a polygraph test.”

Shocked, crestfallen, Bechtel looks over to Dave King, the sheriff’s investigator who’s been working with him since the night Amy disappeared. King looks away. Bechtel turns to McCullough, to the mountain of paper. There’s no time to read them, but he figures the FBI is trying to railroad him. Bechtel says he wants a lawyer.

The request automatically pulls the plug on the interview. Bechtel stammers that he’ll take the polygraph test tomorrow, given a lawyer’s go-ahead. The investigators turn stone-faced, but Bechtel is free to go.

The FBI refuses to comment on this episode or any aspect of the investigation, referring all inquiries to the Fremont County Sheriff’s Department.

“Steve came in for an interview,” says sheriff’s investigator Roger Rizor. “He was confronted: was he responsible for Amy’s disappearance? He was asked to take a polygraph test. His initial response was that he would take it, but the next day he had a lawyer, Kent Spence [son of famed defense attorney Gerry Spence], and he refused the test.”

THE DAY AFTER THE FBI INTERVIEW, sheriff’s deputies arrive with a warrant to search 9 Lucky Lane. For probable cause they cite an unnamed witness who claims to have seen a pickup truck similar to Steve Bechtel’s racing through a Loop Road campground on the day of the disappearance, with a distraught blond woman in the passenger seat. The sighting was reported at a little before 5 p.m., the same time that Steve was phoning Ed Sherline from his house in Lander, a 40-minute drive from the campground.

The deputies come away with Bechtel’s truck in tow and a pile of journals that both Amy and Steve had kept over the past few years.

During the next week, Bechtel begins feeling more pressure to take the polygraph test. The close working relationship between law-enforcement officials and the recovery headquarters is abruptly severed. Even more disturbing, the trust between Bechtel and Amy’s family starts to fray.

“It’s a strain being around Steve, knowing he’s still a suspect,” says Jo Anne Wroe, Amy’s mother. “I know if it were my husband who disappeared and I was asked to take the polygraph, I wouldn’t hesitate a second. Why doesn’t he just take the test so we can all move on?”

Bechtel says he understands his in-laws’ concerns, but he remains adamant in his refusal to take the test. “If law enforcement had just said, ‘Steve, we know you didn’t have anything to do with Amy’s disappearing, let’s just take the poly as a formality,’ I would’ve taken it in a second.

“Now, I wouldn’t take the test under any circumstances. It’s deeply flawed and completely unreliable. You could show the exact same results to two so-called experts, and one will say the subject’s being truthful, the other will say he’s lying.”

While most legal experts support Bechtel’s argument, the media trumpet his refusal to take the test as a red flag and run headlines about a widening rift between him and Amy’s family. Bechtel is rumored to be withholding information from authorities. Gossip, conjecture, and innuendo fill the vacuum left by the utter, haunting lack of solid clues or evidence.

“I’d watch Amy and Steve work out in the gym together, and they never touched or kissed like other couples.”

“Those climber boys, they’re all tight with the sheriff until he starts asking hard questions, then they start crying about polygraph tests and how rough they’re getting handled. Who do they think they are?”

“I see Steve driving around town, tapping his fingers on the steering wheel to the music on the radio. You call that normal?”

TEN DAYS AFTER THE SEARCH OF 9 LUCKY LANE, Todd Skinner gets a call from the FBI, requesting an interview. The agent’s tone is hushed and foreboding. “We’re going to show you a side of Steve Bechtel you’ve never seen before,” he says. “After this, you’re going to look at him in a completely different light.”

Skinner thought he’d already seen every possible side of Steve Bechtel; suspended together hundreds of feet up a rock face in subzero conditions, there’s little place to hide.

At the interview, the FBI agent grimly presents excerpts from Steve’s journal. Meditations on acquiring strength and power. Scattered quotations: “Power is the ultimate aphrodisiac.” An articulate passage on death, written the day after his cousin was killed in the railroad accident. More thoughts on the relationship between climbing and power.

“Okay,” Skinner shrugs. “You can show me the rough stuff now.”

But what fails to faze Skinner disturbs Amy’s family deeply. “When I read that stuff, I was completely freaked out,” recalls her brother, Nels Wroe. “There was material here that just had to be explained. Issues about power and control in that marriage that I’d been concerned about for a long while.”

Amy’s family and law-enforcement officials again press Bechtel to take the polygraph test; again Bechtel refuses. The two camps become more or less clearly defined: Amy’s parents and brother, law-enforcement officials, and old-school Landerites on one side; Bechtel and the local climbing community on the other. Both sides mistrust and denigrate the other’s search efforts.

Meanwhile, other leads sputter and die. It emerges that when Amy lived in Laramie, she was dogged by a stalker of sorts, a middle-aged man who harassed her as she waitressed at a campus coffeehouse. But officials place the man in Bangor, Maine, on the night of July 23 and appear to discount him as a suspect.

Meanwhile, the recovery headquarters maintains its Herculean efforts. Each week scores of the Bechtels’ friends gather to stuff envelopes for fresh waves of mass mailings. New leads—most well intentioned, some frivolous, a few bizarre—continue to flow in. More than 30 psychics contact Bechtel. They see Amy underneath a fir tree. At the bottom of a well. Playing tennis in Portland, Oregon. Waitressing in Fort Myers, Florida.

In order to keep Amy in the public consciousness, a $50,000 reward is announced. “That’s enough to get people’s attention,” Bechtel explains. “It’s enough so that, given the remote chance that there’s more than one abductor, one might turn against the other to collect the reward. I’d give the money gladly and never ask anything more.”

Meanwhile, plans go forward to hold the Loop Road hill race in Amy’s honor. On September 27, about 150 runners show up from throughout the Intermountain West. Race day combines cathartic release with cheerleading. Bechtel exhorts the runners to keep pushing, keep searching, keep distributing posters and flyers. For a few hours the passions, enmities, and suspicions—the sheer helpless rage at Amy’s having vanished without a trace—seem to subside. But not all local runners care to participate.

“I had intended to run,” says Jennie Myers, a 36-year-old nurse who used to win most local road races until Amy moved to town. “I really wanted to show my support for Amy. But then I read about Steve in the papers, about his refusal to take the polygraph test and how he wasn’t cooperating with the sheriff. I started wondering if I wanted to support him or not…If he’s still a suspect, and he has the money to hire a big-shot lawyer, do I need to be giving him my race entry fee, too?”

WHAT PEOPLE THINK ABOUT ME IS BEYOND MY CONTROL, and I really don’t care one way or the other,” Bechtel says. He’s sitting alone in the kitchen at 9 Lucky Lane. No volunteers working leads, no climbers sleeping on the floor, no reporters phoning.

“Those people don’t know me, they don’t know Amy, so it’s just gossip,” he goes on. “But the danger is that other people are going to listen to that gossip, or read in the newspaper that I’m being investigated and assume that I murdered my wife. They’re going to think that the search for Amy is over. Some person who might’ve seen her that day, or who might have some other small but crucial piece of information, won’t come forward.”

Bechtel glances out his window toward the mountains, where the snow has deepened. If by some miracle—or some nightmare—Amy were still alive up there, the snow would only add to her misery. But even more disturbing than the snow itself is what it represents: the passing of a season, the onset of winter. Even Bechtel’s staunchest friends will inevitably lose hope and move on to other concerns. In a few weeks, Skinner and Whisler will strike camp in Wyoming to establish winter climbing quarters in south Texas.

But Bechtel is going nowhere. He vows that the Master the Half will remain in full operation, even if he’s the only volunteer. He dreams about Amy at night and knows, on some inchoate, instinctive level, that she’s still alive.

“There’s this overwhelming sense of void and chaos about this affair, but Steve keeps pushing against it,” reflects Ed Sherline. “In one sense it reminds you of Sisyphus pushing his rock up the hill. But Sisyphus’s task was absurd; his rock just kept rolling back down. Steve’s task isn’t absurd. Amy’s at the end of it. And if he doesn’t find Amy, then the methods he’s developed will help some other family find their lost girl.”

Steve Bechtel refuses to think in such terms. “I’m not done yet,” he says. “I can’t quit on her now, because if the situation were reversed, I know Amy wouldn’t quit on me.

“I know people will look at the odds against her being alive, look at the complete lack of clues, and say it’s impossible that she’ll ever come back. But people said it was impossible for her to become the runner that she is. Amy proved them wrong once,” Bechtel concludes, pulling his notebook of leads toward him and turning the page. “She’ll just have to prove them wrong again.”

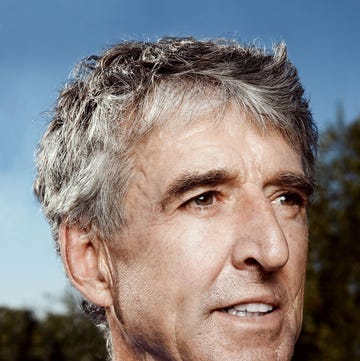

Story Update · August 18, 2016

Nearly two decades have passed since Amy Wroe Bechtel disappeared, and few leads have since emerged. Steve Bechtel was never charged in the case and still lives in Lander; he’s remarried with two children and operating a gym in town. Meanwhile, a new lead detective, John Zerga from the Fremont County Sheriff’s Office, was recently assigned the case and is re-examining details about the initial investigation’s mismanagement, and the myriad twists and turns in the case over the years. His investigation has renewed public interest in an old tip that placed current death-row inmate Dale Wayne Eaton, found guilty in 2004 for the murder of another young woman in 1988, in the area at the time of Amy’s disappearance. Steve Bechtel, however, is pessimistic. “As much as Eaton makes an attractive suspect, I don’t think we’re ever going to learn anything from him,” he wrote in an email to Runner’s World. “I think trying to point the finger at him just [provides] a convenient answer in a situation where there are no answers. With every passing year the likelihood of finding useful information decreases.” In the August 2016 issue of Runner’s World, writer Jon Billman, who lived in Wyoming in 1997, describes what’s happened in the 19 years since the runner went missing in “Long Gone Girl.” –Nick Weldo