THE GRANDSTAND AT MARSHFIELD HIGH SCHOOL is nearly empty, but it seems like everyone in Coos Bay, Oregon, is on the track. People are crossing the finish line in every way possible—the buzz-cut high school kids out in front, the stoic folks wearing earbuds, the willowy 9-year-olds accompanied by red-faced parents. Old-timers limp around the turn to huge applause. A handful of people propel themselves toward the finish line, unashamed of the spittle hanging from their lips and of their gasps and of having run themselves ugly. And then there’s me up in the grandstand in my jeans and my Chuck Taylors and my different kind of ugliness.

Last night, driving down from Portland for the Prefontaine Memorial Run, I almost convinced myself that I was still a runner. As I swept past the dunes and onto the Coos Bay Bridge, I gave it one last college try: If you’re seriously going to look for him, was my logic, you’ve got to get yourself on that starting line. The opening bars of “Born to Run” were soaring out over the Pacific, and the idea of lacing up my old New Balances and chasing after his ghost no longer seemed like such a potentially stupid and/or painful idea. Maybe all this time off was exactly what I needed. Maybe it was like I’d been tapering for the past couple years. Maybe I even had a sub-40 in me.

Waking up in my motel this morning, however, the prospect of running a 10K on absolutely no training seemed about as relevant to my task as slaughtering a cow would to a food critic. Just the thought of pinning a number to my chest made me want to reach for the Advil.

And so, instead, I’m in the grandstand staring at all these people. Aside from his face stuck to a bunch of sweaty T-shirts and the occasional fake mustache, there is absolutely no sign of him. What the hell got into me last night? I can’t put it all on Bruce Springsteen and the late summer air. What an idea, to think that just because I’ve come to his hometown, Pre might actually appear. I’m at his memorial run, for goodness sake.

Maybe this is what happens when you sit in the grandstand. Maybe this is what you do when you’re a spectator, a fan of distance running—you end up judging everyone against someone who’s been gone for 38 years. What an idea, creeping around Coos Bay, hoping to uncover something that hasn’t already been looked for a million times over. Everything’s already been said about Steve Prefontaine—he said it all himself first, and we’ve just been repeating and repeating his words until they’ve hardened into one giant Nike slogan. If there’s any trace of him left, I don’t know where to find it.

ANYONE WHO HAS FALLEN under his spell can recall it happening. This is my version. In the spring of 1994, I was 13, and my family had just moved to Oregon. My older brother and I were sports fans. Fans, in general, of anyone possessed by that unique, unsustainable intensity that we called “American.” Axl Rose. Bo Jackson. Ferris Bueller. Kurt Cobain. These had been our guys. But Axl started wearing spandex. Bo got hurt. Ferris wasn’t real. And Kurt’s body had just been found. So we were in the market for a new hero.

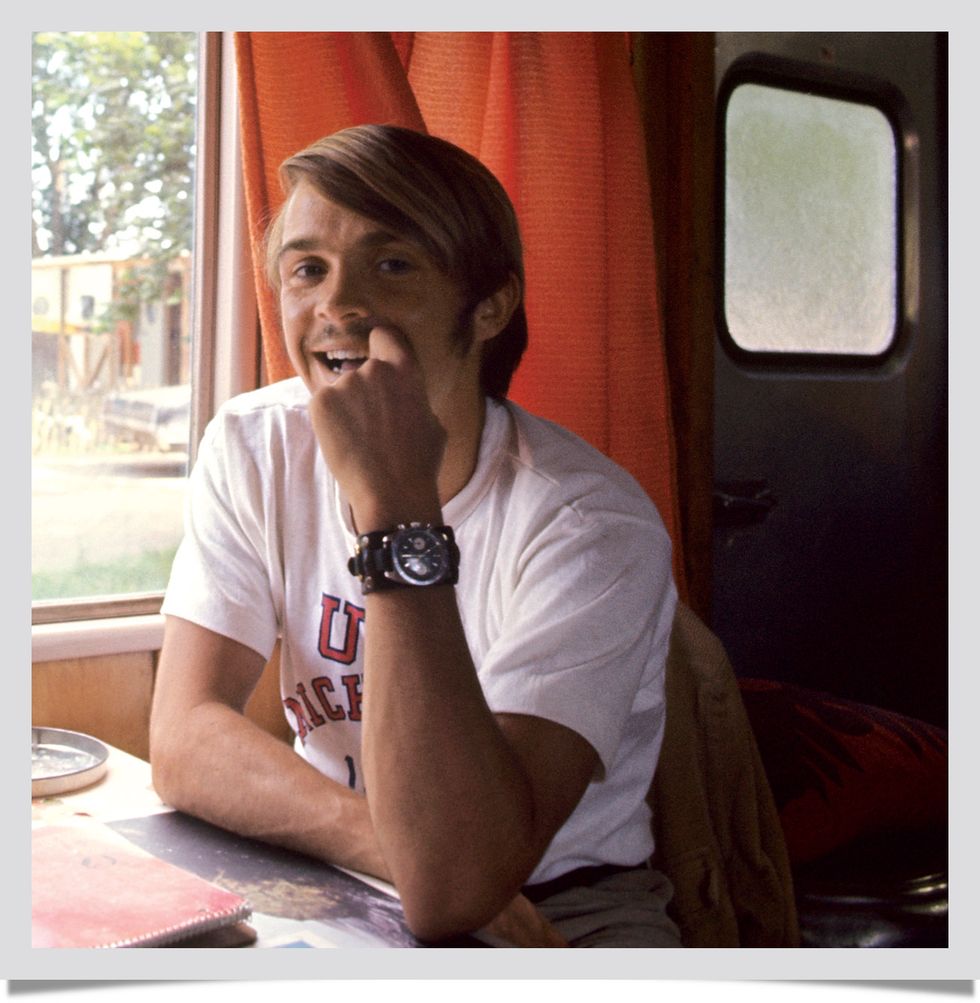

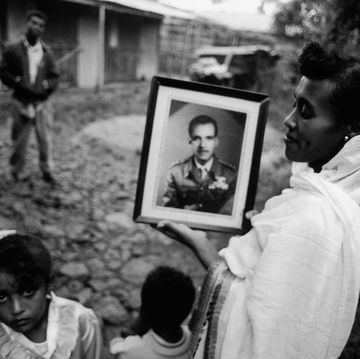

What I remember is that Mom was driving us home from our monthly ransacking of the Central Library. As usual, my brother had called shotgun. From where I was sitting, in the backseat, my brother’s life had taken an unexpected turn. He was becoming a jock. Okay—a half-jock. My brother and I had always been sports-crazy, but as much as we dreamed about playing quarterback or even backup point guard, those dreams were confined to our backyard. We simply didn’t have the size for those sports; our parents were maybe five-foot-four. And so, the previous fall, almost apologetically, my brother had gone out for the one team that never cuts anybody: cross-country. And here he was, eight months later, the fastest kid in the freshman class. Just like that, his life had gotten interesting. Now, in the car, he was bent over a beat-up little book, flipping through photographs of an undersized, liquid-eyed runner. And I was right behind him, clinging to the seatback, trying to read the captions over his shoulder.

“Who is that?” I kept asking. “Who is that?”

“He’s dead,” my brother finally said.

“How’d he die?” I asked, fighting my seatbelt. My brother held up a photo of a rock wall. Painted in the middle was this:

pre 5-30-75 r.i.p.

He closed the book.

Pre, said the cover.

“Were you guys always this morbid?” my mother sighed. “Can’t you appreciate anyone who’s alive?”

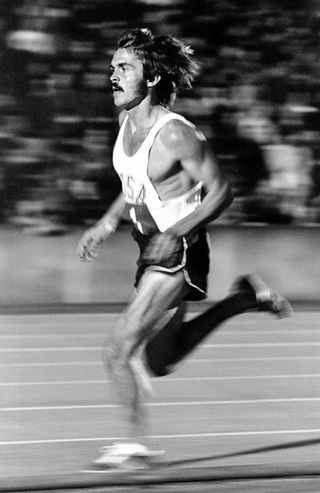

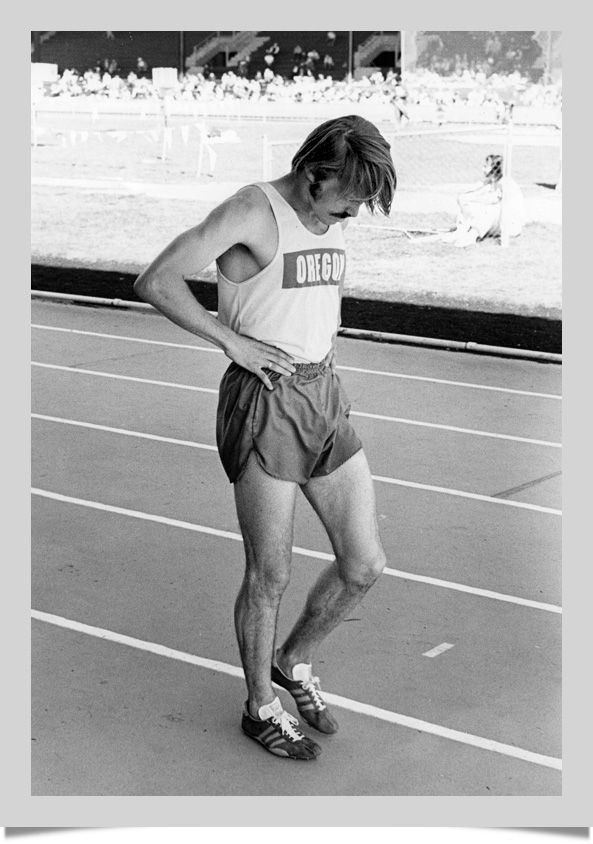

IN 1975, at the age of 24, Steve Roland Prefontaine died in a single-car accident. At the time of his death, he held every American record from 2,000 to 10,000 meters and was a favorite to win at least one gold medal in the 1976 Olympics. The subject of two Hollywood movies, two documentaries, and four books, he is one of the most-analyzed athletes in track-and-field history. On the message boards of letsrun.com, the distance running Web site, his acolytes argue about everything from the circumference of his ankles to the number of women he slept with. Then there’s the matter of his one Olympic race, his fourth-place finish in the 5000 at the 1972 Munich Games, an event widely regarded as the most exciting race ever run.

Pre brought the same urgent swagger to distance running that Muhammad Ali brought to boxing. When Pre talked about running, he made it sound more macho than football, more illuminating than poetry. “The best pace is a suicide pace,” one saying attributed to Pre has it, “and today is a good day to die.” In the documentary Fire on the Track, his rivals, training partners, and coaches speak of him as a kind of savior, a man who transcended not only his sport but life in general. The film is narrated by another Oregon legend, Ken Kesey, who wrote novels about men like Pre: blue-collar, idealistic, a little dangerous.

For most of his career, Pre lived on food stamps. He risked his amateur status while fighting for athletes’ rights, paving the way for track and field to become a professional sport. Toward the end of his life, he became one of the first employees of Nike. An empire sprang up in his footsteps. Every summer, the sleepy college town of Eugene hosts the Prefontaine Classic, one of the few world-class track meets in North America. Every September, in Coos Bay, his hometown on the coast, more than a thousand people trace one of his old training routes, a 10K up the hills and back. Just as he did, they finish on the Marshfield High School track—the same track where he broke his final American Record three weeks before his death. I could have been one of them, but instead, I’m just up here, watching.

FRESHMAN YEAR—surprise, surprise—I went out for cross-country. My first season, with more than a year of Pre-worship under my belt, I won almost every race. So what if I was competing only against other freshmen? My times were faster than Steve Prefontaine’s were when he was 14. All I needed to do was drop my mile time 20 seconds a year for the next couple years and I’d stay right on target.

I studied photos of the two of us in action, comparing my form to his. When Pre was clean-shaven, he looked like a movie star. Eventually, as if trying to complicate his good looks, he grew a big, bushy mustache. After that, he looked like a movie star with a big, bushy mustache—James Dean playing Paul Bunyan. Some people, in fact, referred to him as the “James Dean of Track.”

Examining those photos, it seemed to me that we had the same exact build, the same chesty power. Sometimes, if the wind was blowing the right direction, my hair would even sort of do that Pre thing. It was pretty obvious that nobody else on the team, not even my brother, resembled him as much as I did. After races, I would gaze meaningfully at the kind of girls who, just two months before, I never would have dreamed of asking out.

PRE DETERMINED

Any debate regarding Steve Prefontaine’s merits as an all-timer should begin with these numbers.

0 Defeats in cross country or track during Pre’s junior and senior high school seasons

19 Pre’s age when he appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1970

3 Any debate regarding Steve Prefontaines merits as an all-timer should begin with these numbers

4 National titles earned in the three-mile while at Oregon. Pre was the first track athlete to win four straight in the same event.

0 Losses in races longer than a mile while running at Oregon

35-3 Overall record in the mile at Oregon’s Hayward Field

40 Years Pre’s U.S. Olympic Trials 5,000-meter record (13:22.8) stood, until Galen Rupp broke it by less than two-tenths of a second in 2012

.64 Defeats in cross country or track during Pres junior and senior high school seasons

7 U.S. records set in distances between 2,000 meters and 10,000 meters (his three-mile and six-mile marks still stand)

$5,000 Yearly value of the contract Pre signed with Nike in 1974, when he became one of the shoemaker’s first athlete endorsers

78% Pre’s lifetime outdoor track win percentage across all distances (119 wins in 151 races)

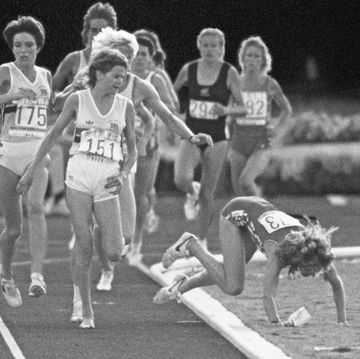

MUNICH 1972. We watched it at camp, more than two decades later. Running camp: band camp with lower body fat and more exposed skin. While one of the counselors was getting all reverent about the honor of going for the gold, we campers were jockeying for position around an ancient television. It would only last about 13 and a half minutes, but that was more than enough time to get cuddly with other Olympic dreamers.

In the upper-right-hand corner of the screen was the clock, huge and analog and intimidatingly Teutonic. We recognized most of the guys in the race from the photos in Pre. We booed Lasse Virén, the villain. We booed Ian Stewart, the even bigger villain. “You’re so tall and boring,” we yelled, “so pale.” And there, in their midst, was our guy. He had more style in one strand of his sunbleached hair than the rest of the field put together. His hair was magic, communicating all sorts of unsayable things. Even during those first two miles, when we already knew what the outcome was going to be, we had this irrational fear that if we took our eyes off him we might miss the entire point of the race. Meanwhile, our hands were scooting along the dusty floor, finding wrists, elbows, fingertips in the dark. Every running camp romance started and ended with Steve Prefontaine. This was pretty much the most intense 13 and a half minutes ever.

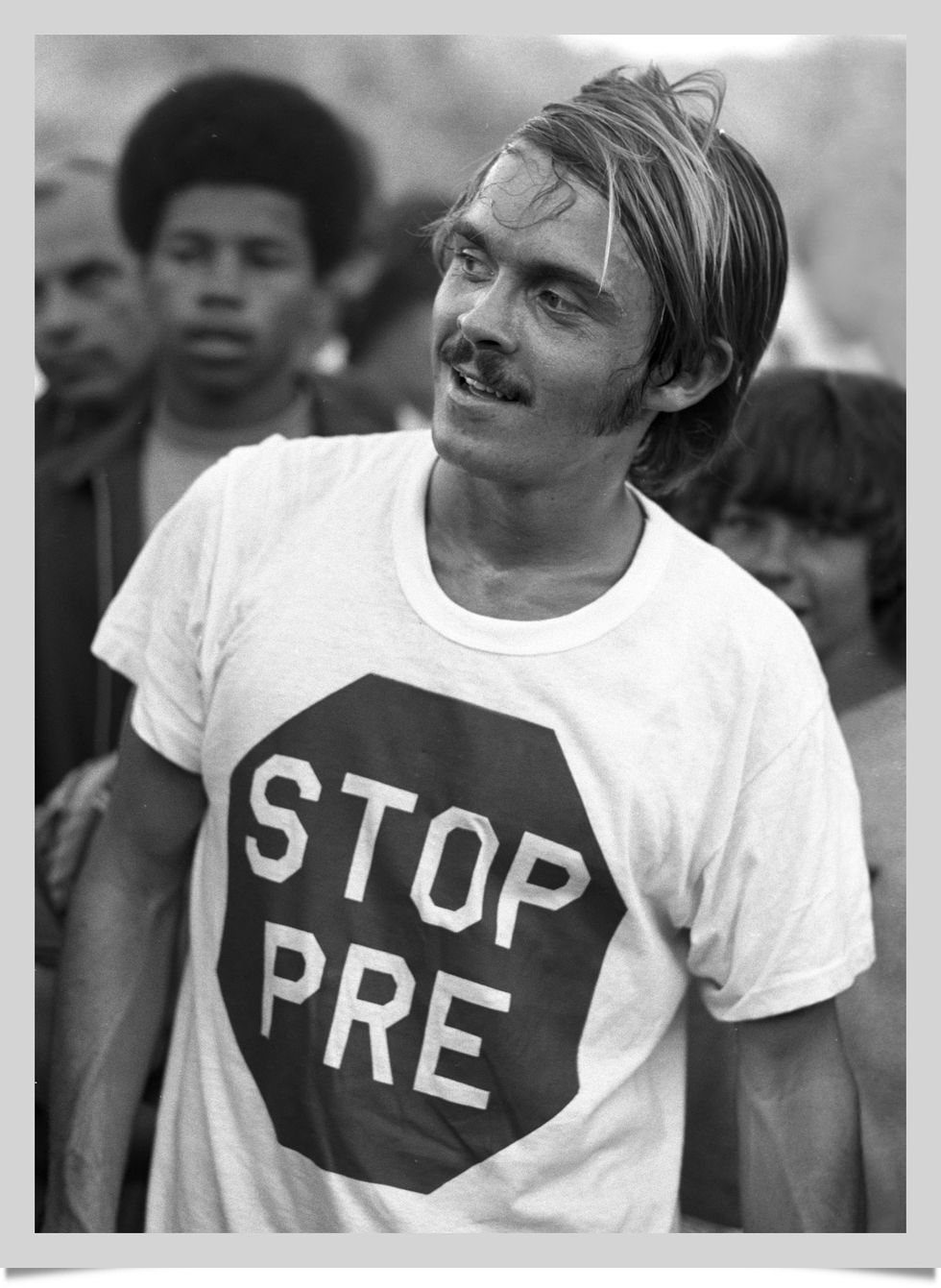

Up front, some brainy kid was trying to argue that the most iconic thing about him—the mustache—symbolized failure. “He was basically unbeatable,” said the kid, “and then he grew the mustache.”

“Why is it so iconic, then?” we asked.

“Because we as a culture fetishize failure,” the brainy kid said.

“Maybe you as a culture fetishize failure,” we said.

“That doesn’t make any sense,” the brainy kid protested, but he was too late, we weren’t listening anymore, because there were only four laps to go, and Pre was surging to the front.

“Go, Pre,” we found ourselves whispering. He was so much smaller than the rest of them. So much more alive. Go, Pre. We wrapped our arms around ourselves and started rocking back and forth, back and forth. We were no longer so certain that he was going to lose. Maybe we had it all wrong. Maybe he’d get away this time.

PRE NEVER GOT AWAY. But I did. After Hollywood released two movies about him in less than two years, the illusion that Steve Prefontaine and I shared some kind of primordial, E.T.-style bond began to dissolve. One of my teammates claimed “pre1972” as his email address. Another started putting in 15 or 17 miles every Sunday, pounding along the train tracks and through the bleakest industrial sections of town because that’s what Pre did. As for me, my mile time was the same-old, same-old. That whole “20 seconds a year thing” was something I preferred not to think about. Sometimes, during practice, I’d mock Jared Leto’s tone-deaf Prefontaine monologues until what was meant to be inspirational became an excuse for a midpack finish. “All of my life,” I’d inform my teammates, “people have said to me, ‘You’re too small, Pre. You’re not fast enough, Pre. Give up your foolish dreams, Steve.’ But they forgot something: I have to win!” I might not have been living up to my potential, but at least I wasn’t as cheesy as Jared Leto.

IT WAS LIKE ANY BREAKUP: I made a lot of noise about how I’d never go back, never be a runner again. As if saying it aloud enough times would make it real. But even in the middle of winter there was this restless part of me that knew that when the snow began to melt, I’d be lacing up my old shoes and chasing my old dreams. There was this part of me that knew no deeper pleasure than being the first one out the door, the first one on the trail, crashing through spiderwebs and leaping over puddles and picturing myself as him. I broke 17 minutes in the 5K exactly one time. I was nothing special as a runner, but sometimes when I was out there, I’d forget that.

Like any breakup, though, the pain of going back eventually outweighed the pleasure. Each year I was a little slower, a little farther away from where I’d wanted to be. There were other dreams to pursue. I turned 30. Life, it seemed, shouldn’t be measured by PR’s any longer. Stop beating yourself up, I kept saying, and finally, two years ago, I went cold turkey. Since then, I’ve put on 15 pounds. I’ve learned how to get through the day without breaking into a sweat. And I can’t really remember what that last hard mile feels like.

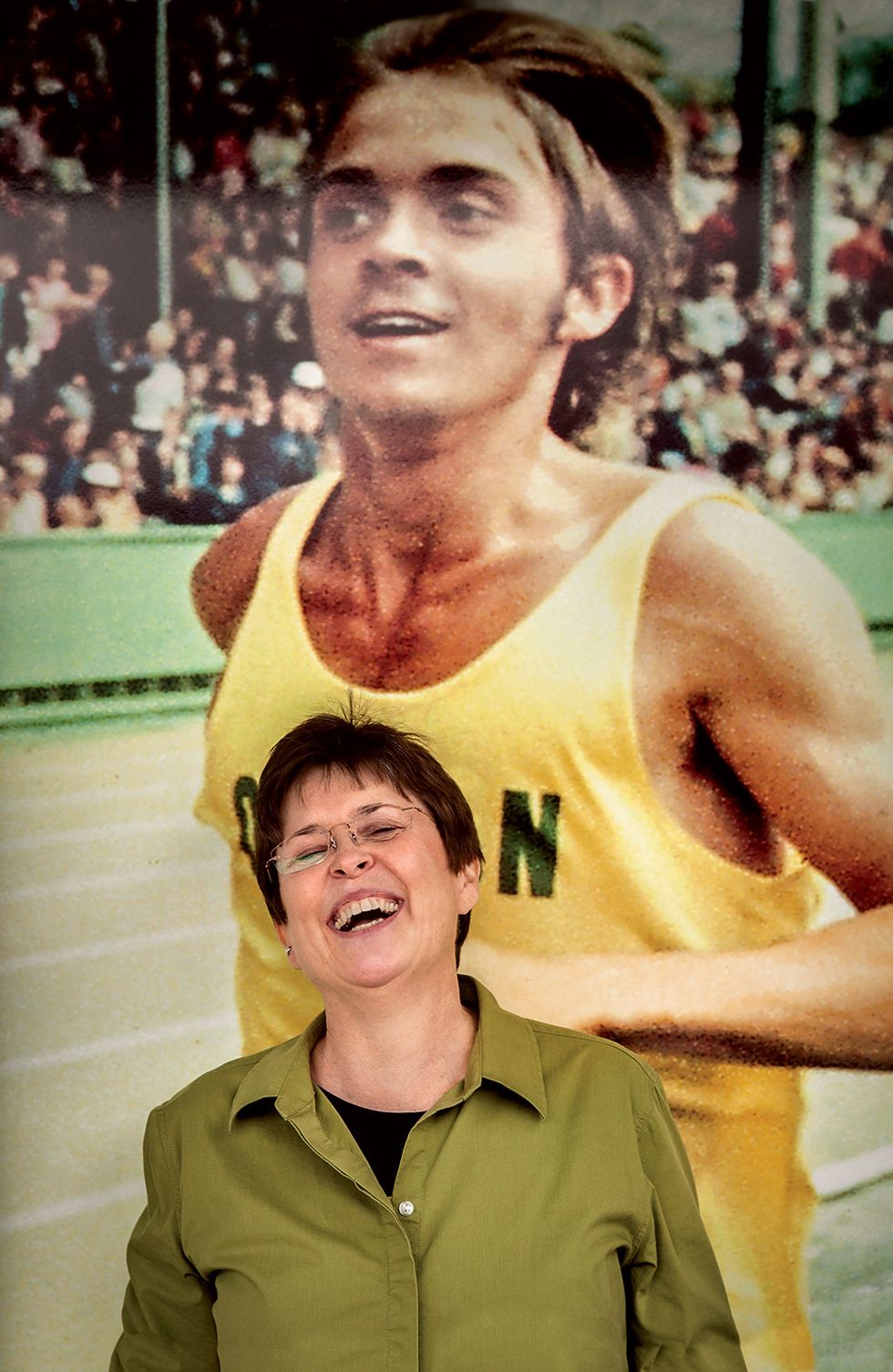

HOW LONG have you been working for Runner’s World?” Elfriede Prefontaine asks me. “Four days.” I say. “It’s kind of a new thing.”

Elfriede says something unmistakably Prefontaineish about setting the record straight. She’s still upset that Hollywood got the facts wrong about her son’s injury at the NCAA Cross-Country Championships in 1970. He hurt himself at the pool, she says, not in the bedroom. I ask if she minds if I record our conversation.

“I hate interviews,” she says.

I assure her that I understand, and I do. It’s a relief not to have to worry about asking her the right questions.

“Did you run today?” she asks me.

“I thought about it,” I say, “but I was afraid that I’d spend the rest of the weekend in my hotel room icing my knees and drinking beer. I probably wouldn’t be here talking to you if I’d run.”

And I definitely wouldn’t be talking to her if I hadn’t pulled myself together back in the grandstand and introduced myself to John Gunther, sports-section editor of The World Newspaper of Coos Bay, who in turn introduced me to the Pre Committee, the volunteer group that organizes the memorial run, some of whom were Pre’s high school teammates. Most still run. “We’re going for lunch after,” committee member Jay Farr said as the awards were being handed out. “You hungry?”

I was starving. And curious about these guys. And so I followed the gang into this restaurant with absolutely no idea that waiting inside would be Pre’s mother and sister, Linda. But here they are. And just like that, I’m eating lunch with the Prefontaines. Part of me wants to run outside and call my brother and my former teammates. The rest of me is like, Eat your damn lunch and chill out.

As we eat, I learn that Farr went to Yale and owns two hardware stores. His buddy John Burles is quick to move the conversation back to what matters. Pre was a “punk,” he says, who loved to run his mouth and was used to getting chased.

“I was a senior when he was an eighth-grader,” Burles says. “One day we were running intervals, and he came down to the track and announced that he was gonna run them with us. Two-twenties. About the fifth interval he started dragging, and shut his mouth after that. But then I went off to college, and after that, of course, the whole Marshfield track thing started getting pretty interesting.”

With some pride, Farr points out that back in high school, he once beat Prefontaine in the 440. “It wasn’t really Steve’s distance,” he laughs. Today he finished the Pre 10K in just over 51 minutes. Burles asks him where he placed. “I think I was in the top 10,” he says.

“Top 10?” Burles says. “Oh. You mean in your division.”

“Well, it won’t get any better,” Farr says. “All those guys turn 60 next year.”

“I’m just impressed you’re still running,” I say.

“My advice to you,” Farr says, “is to get in shape. And stay in shape. Enough of this back and forth business.”

“Any other advice?” I say, laughing.

“Make sure you talk to Pat Tyson,” Elfriede says. “Tell him I say hello.”

“What about current runners?” I ask Pre’s sister, Linda, who is 59. “Do any of them remind you of him?”

“I like Nick Symmonds,” Linda says.

“I like him, too,” I say.

“He’s got some spunk,” she says. “Do you have a card?” I hand one to her.

“I want you to know,” she says, looking at it, “that if you screw this up, I’ll come after you.” She gives me a big smile. I smile back. I know Linda’s not joking. She reaches out and pretends to pinch my cheek like I’m 5. “I’ve been wanting to do that to you the entire time,” she says.

Out in the parking lot, we say goodbye. Some committee members are off for a big hike tomorrow. Where do these old guys get their energy? I keep thinking about Farr’s advice: Get in shape and stay in shape. Maybe it’s not such a bad idea.

The Prefontaines, as is their tradition on the weekend of the memorial run, are heading off to the cemetery. Elfriede is 88. Her husband, Ray, died just a few years ago. Steve had good genes. He should have lived till he was 110. As Linda and Elfriede climb into their car, I can almost picture him in the backseat, but it’s Steve as he was, Steve as a boy. “I’ll run next year,” I say to nobody in particular.

MAYBE YOU’RE LIKE ME. Maybe you’ve also gone looking for him. Or maybe you’ve just thought about it. In a sense, every time you go to a meet at the University of Oregon’s Hayward Field, you’re paying him a visit. But one day after a meet you realize that the time has come to make the pilgrimage to that sharp curve of Skyline Boulevard in Eugene, to his rock—the place where he died. And so you’re standing there in front of the 5-30-75, but instead of thinking about him, you find yourself wondering what it’s like for the neighbors to have to drive past the rock every night. You wonder if they take the curve slower because of it. You leave the rock feeling vaguely unsatisfied, like maybe you didn’t really honor him properly. And so one warm September weekend you decide to come out to the coast so you can really give him his due. You poke around Coos Bay, reminiscing about your own running history, waiting for some kind of spectacular epiphany. This is where he ran, you keep telling yourself, these are the streets. Every time you climb into your car, “Born to Run” explodes from your speakers. The album came out in ‘75, a few months after he died. After lunch, after the crowds have left, you return to the track at Marshfield High. You circle it once, walking, taking your time. At the finish line, you get down on your hands and knees and actually bend down and kiss the track. You hope that nobody can see you from the houses on the hillside. But so what if they can? They’re probably used to it.

You leave your car at the school and walk down to the main drag. You’re looking for a bar. You’re finding a bar. You’re treating yourself to a beer. You’re treating yourself to another. Your mind is racing. Your smartphone is out. It wouldn’t take a genius to figure out the address. It wouldn’t take an extraordinary amount of guts to knock on the door, to ask if you can see his bedroom, his ribbons, his life. You know you shouldn’t be doing this, invading his home, but you tell yourself that you can’t really help it.

You signal for the check. By the time you get up from your barstool, you’re dizzy, but not because you’re drunk. You’re struck by the thought of how many have come before you, how many have felt entitled to his life. How many haven’t been able to help themselves. How many haven’t realized that it’s time to start looking elsewhere.

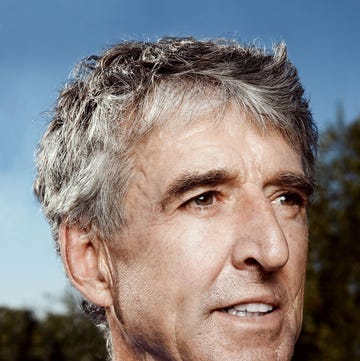

“Of course Prefontaine was my first running hero,” Nick Symmonds says. “I think you can assume that of every high school distance runner. At some point or other you’re gonna be at a cross-country camp, or a cross-country sleepover, and somebody’s going to pop in Without Limits.”

Symmonds and I are sitting outside a coffee shop in Eugene on an unseasonably warm October day. He’s drinking Dr Pepper and looks ready for a photo shoot. With the sun in my eyes and a five-time national champion across the table, I’m feeling pale and out of shape, jacked-up in all the wrong ways on my third coffee of the day. I’m trying to get to the bottom of why Symmonds became a runner.

“The ironic thing,” he says, “is that these days, I’m built more like a hockey player. I got into distance running in high school because I wasn’t built like a hockey player. I didn’t go through puberty till I was about 15. I fought it, I resisted it, but sophomore year I started to give in—I started to enjoy running a little bit.”

I ask him what it is about Prefontaine that draws so many people in.

“He was just a guy who wasn’t afraid to live his life,” Symmonds says. He hesitates, his eyes flash, and just as decisively as I’ve seen him burst out of the pack, he says it: “What kid doesn’t want to sleep with beautiful women and drink beer?”

THE FIRST TIME I saw Nick Symmonds I didn’t really want to see him. It was the 2008 Olympic Trials, and I’d agreed to spend two long weekends in the bleachers at Hayward Field with my family. We’d bought our tickets years earlier, long before I decided to move to Nicaragua and write my Great American Novel. On the eve of the Trials, I flew back in such a reluctant fog that I ended up missing my connecting flight in Mexico City. I couldn’t quite believe I was trading in another eight months of living abroad for eight days of track and field, a sport I’d stopped following in high school.

When I wasn’t grumbling about how reserved everyone in Oregon was, how white, I was trying not to wonder what would happen to me if the novel didn’t get published. It didn’t occur to me at the time, but this was a mind-set that the athletes down on the track would have understood. Top three went to Beijing. Everyone else got to figure out what to do with themselves for the next four years.

The consensus was that the men’s 800 was going to be “fun.” There was Andrew Wheating, the six-foot-five, happy-go-lucky University of Oregon kid who’d only been running competitively for two years. There was Khadevis Robinson, the four-time national champion who talked as quickly as he ran. And there was Nick Symmonds, the burly dude from the D3 school with those short, choppy strides, who came out of nowhere last year to beat the defending Olympic Champion in the Prefontaine Classic.

While watching him move through the qualifying rounds, I began to realize that there was something familiar about Symmonds. It wasn’t his tactics—the 800 is two laps, and Symmonds almost always went out in last place, then worked his way through the pack and pounced somewhere on the final turn—no, what was familiar about him was him. His attitude. The way he raised his arms when getting introduced. The drama of how he raced. Even his blond hair. But let me be clear: Nick Symmonds reminded me of Steve Prefontaine the way a song at the bar reminded me of an ex-girlfriend. Nick Symmonds reminded me of October 1995, of the 14-year-old badass I so badly wanted to be. Nick Symmonds reminded me of how I used to strut through the hallways the day after a PR, picturing my new time hovering over my head like a sexy neon hologram. Nick Symmonds reminded me what it was like to think I was going to be the next Steve Prefontaine. The difference, of course, between 14-year-old me and Nick Symmonds was that Nick Symmonds was good enough to do something about it.

THIS IS HOW YOU DO IT,” Symmonds says. “Create a series of meets—L.A., New York, Chicago. Get the best talent. And invite people to come, drink beer, and bet on the athletes like they would on horses. I know purists don’t want to hear it. They say, ‘People should like track and field because it’s such a beautiful, pure sport.’“

“Hmm,” I say. “Negativity might become a problem.”

“You know what would be a problem? Not having track and field in America anymore.”

It’s difficult to tell if Symmonds is joking. I don’t think he is. We’ve been talking about why track isn’t more popular these days. The reasons are endless—the spotty TV broadcasts, the absence of more world-class outdoor meets in the United States, the lack of financial payoff compared to other sports (highlighted by the controversial Rule 40, which prevents athletes from mentioning sponsors or displaying logos just prior to and during the Olympic Games, a rule that Symmonds and many others spoke out against in the last Olympic cycle)—but more than anything, the problem is that track is ignored by 99 percent of the population in non-Olympic years.

Symmonds has a keen understanding of how quickly he will be forgotten. He did what he could to seize the moment last summer, those not-quite-two-minutes when he circled the track in London two times. He went on a date with Paris Hilton. He broke the U.S. record in the beer mile. He auctioned off real estate on his left shoulder, promising to wear a temporary tattoo of the logo of the highest bidder. He was then told that if he didn’t cover the tattoo up with tape, he’d be kept off the starting line. It was a publicity stunt, but it presented the reality of Rule 40 in a clear way. There are few ways to make money as a runner. Most will retire with little or no savings.

“What’s wrong with track and field right now,” Symmonds says, “is that we’re not marketing it the right way. I’m sad that we’re more interested in what the Kardashians are doing than what Galen Rupp is doing. But you can sit here and moan that American culture doesn’t appreciate the nuances of distance running, or you can make distance running more interesting to that culture.”

“I’m just imagining somebody blowing a lot of money on you,” I say. “They’d be like, ‘Dude, you’re off trying to get dates with Paris Hilton, and I lost $15,000!’”

“I can’t change the fact that my race is less than two minutes,” he says. “But I can change what I’m doing off the track.”

“Can we talk about what you’re doing on the track?” I ask.

“What do you mean?” he says.

“The Olympics,” I say.

“Oh, man,” he says, shaking his head. “After the Games this year, everyone wanted to know how I felt. I kept saying how ecstatic I was to PR in the final. I mean, I never thought I’d run 1:42.”

I can’t stop myself from blurting out I never thought he’d run 1:42 either. With those hockey-player strides? That fight-through-the-pack mentality? Impossible.

“But the truth is,” he says, “the whole thing was eating me up.”

If you missed the 800 at the Olympics last summer, put the magazine down and YouTube “Rudisha world record London.” Symmonds ran exactly the race he wanted to run, but so did everybody else.

“This is the thing about running,” Symmonds says. “On the one hand, you want to sit back with your feet up and say, ‘I’ve done it. I’ve made two Olympic teams. I was part of one of the greatest races in history.’ But what you have to understand is that elite athletes are some of the most discontented people you’ll ever meet.

“I really, really felt like I should have won a medal with that performance. I went to my sports psychologist and laid this on him, and he said, ‘If you’d taken bronze, how would you feel?’ And I said, ‘Oh man, I’d be so happy that I got bronze.’ And he goes, ‘But would you be frustrated that you didn’t get silver?’ And I’m like, ‘Of course!’ And he goes, ‘Well, what if you got silver?’ And I said, ‘Well, I would have been pissed off that I came that close to gold.’ And he goes, ‘And if you’d won gold?’ That’s when I realized that even with a gold medal, I would have always worried that in a different year I would have lost to someone better. It’s just the way that elite athletes—in track and field especially—are wired. To always be a little insecure about what you’ve accomplished. In the big scheme of things, I’m the sixth-fastest man in the world at the 800, and I just feel embarrassed about it.”

“You what?” I say.

“That’s just the way I feel,” he says. “You’d think at this level that you would never feel this way, but I’ve sat at tables with David Rudisha and Sanya Richards-Ross and the crew and just kind of looked around, and I’m like, I’m the only one without a medal. I’m not fast enough. I don’t belong here.”

After meeting with Symmonds, I take Elfriede Prefontaine’s advice to heart, and give Pat Tyson a call. Tyson was Pre’s roommate and training partner during their trailer-dwelling, food stamp—collecting days. In the Jared Leto movie, Tyson is played by Breckin Meyer. Nowadays, he’s a legendary coach. His teams at Mead High School in Spokane, Washington, were some of the greatest cross-country teams ever. He eventually transitioned to college and is currently building up the program at Gonzaga University.

We chat while his runners are off on a workout. Tyson is jazzed about the state of American distance running, and not just at the professional level. “We’re doing something right in the U.S.,” he says, rattling off the names of a dozen young runners to keep an eye on. I ask him if any of the runners he’s mentioned might have an interesting perspective on Pre. He suggests I look up a couple of guys at the University of Portland. “What’s the biggest difference between coaching high school and college?” I ask.

“The advantage of high school,” he says, “is that you get to them earlier. There’s less garbage in a ninth-grader. By the time they get to college, most runners think they know what they’re capable of—what their limits are. But a ninth-grader thinks he’s Peter Pan. I’ve always felt like a good coach should let his kids go with their instincts, or how will he know if he’s taking away their art?”

“What did you learn from Pre?” I ask.

“Like was there one thing I learned?”

“I guess that’s a pretty broad question.”

“Hmm,” Tyson says. “Pre knew how to turn it on and when to turn it off. Before a big race, if he could see that I was starting to obsess, he’d tell me, ‘You’re not good enough to worry.’ That’s a perspective I try to communicate to my kids.”

“What’s your biggest challenge?”

“Getting my kids to think like ninth-graders,” he says.

THERE’S A SEQUENCE in the Fire on the Track documentary that I can’t stop watching. It’s July 1972, and Pre has just qualified for the Olympics in front of his home crowd in Eugene. “Who is foremost in your mind in Munich?” asks a reporter.

“Well,” Pre says, reaching out to sign autographs, “there’s gonna be 12 people in the final event, and if I’m there, there’s gonna be 12 people that can win.”

He’s at the center of a mob, mostly kids. His hair is streaked across his forehead. The mustache is maybe two weeks old. He’s wearing that famous “Stop Pre” T-shirt. He’s just won the 5,000. Broken the American record. Set an Olympic Trials record that will last 40 years. For a notoriously handsome man, this might be his most handsome moment. The bravado is spectacular. But if you really parse what he’s saying, you realize how strangely democratic it is. He’s not promising victory. He’s promising to run a race that will give everyone in it the opportunity to do something special. He’s 21 years old.

RUNNING,” I SAY, “it’s so close to being nerdy—” “Yeah!” Jared Bassett and Izaic Yorks shout in unison. It says something, how enthusiastically they agree with me.

Bassett and Yorks run for the University of Portland, one of the top distance programs in the country. Bassett, a senior All-American, is the second-best runner in Marshfield High history, second only to Steve Prefontaine. Yorks, a freshman, is a top middle-distance recruit.

My dinner companions are confident yet polite—the kind of young men who make me think about teaching again.

Bassett, 22, is blond and wiry, a steeplechaser. His recent wedding made a lot of noise in The World Newspaper of Coos Bay. He’s just finishing up nursing school and doesn’t seem fazed by the possibility of having to find a job in order to fund his running after he graduates. There’s a tiny possibility he’ll get a shoe contract, but he’s realistic about his chances.

Yorks, 18, is taller, more muscular. His backward cap seems more like a nod at youth than an actual sign of rebellion. When I ask him why he chose UP out of all the schools that wanted him, he says, with complete sincerity, “It was the closest to my family.” A few days ago, when I set up the interview, my call kept getting dropped. I was trying to explain to Yorks that he didn’t need to worry, I wasn’t going to describe him as the next Steve Prefontaine. Finally, after three or four tries, when I managed to get to the end of the sentence, he said, totally unruffled, “Of course not.”

“Do you picture yourself at the Olympics?” I ask now.

“Oh, yeah,” Yorks says. “Every night.”

“Are there runners out there that you find intimidating?”

“Not particularly,” Bassett says.

“Not really,” Yorks agrees. “I guess I never get scared of them.”

“If you do,” Bassett says, “you put them in front of you before the race starts.”

I think back to my own racing days—that dread before a big meet, that everyone wanted it more than I did. “Why are we still talking about him?” I ask. “He ran a 3:54 mile; 13:21 for the 5000. Didn’t medal. A lot of people have run faster.”

“It was the way he raced,” Yorks says. “All his feelings were visible. Everything was out there. People relate to that stuff.”

“What do you think Pre would be doing if he were alive?” I ask.

“People say he’d be high up at Nike somewhere,” Bassett says. “I don’t think he would. I mean, Nike’s a great company, don’t get me wrong, but I don’t think he thought it was going to be this big crazy thing. Honestly, I think he’d be coaching. Down in Eugene. Or back in Coos Bay.”

MY FRIENDS DEMPSEY AND ALY have never been to a cross-country meet, so I persuade them to join me at the WCC Championships. It’s 9:45 a.m. and typical cross-country weather: awful. The clouds are so heavy and close it feels like the raindrops are materializing somewhere around the treetops. The ground is bubbling beneath our feet. I explain to my friends that we’re cheering for the purple team. By the second loop the runners are covered in mud, so I’m impressed when Dempsey and Aly are able to pick Bassett and Yorks out of the pack. The University of Portland, ranked number 17 in the country, is in a dogfight with Brigham Young University, ranked fifth. Also in the mix is Gonzaga. We watch Pat Tyson sprint from one side of Fernhill Park to the other, intercepting his runners twice per loop. “I’m trying to imagine a football coach moving like that,” Dempsey says.

We’re camped out at the bottom of a slippery little hill from which we can see the entire course. It’s an important meet, and free, but the majority of the people in attendance are on one of the teams. Then there are those of us with umbrellas. Maybe 100, 150 umbrellas. Aly gets excited when she overhears something involving the words “rip” and “asshole.” “I didn’t know there would be bad language at a cross-country meet!” she exclaims.

“Isn’t it great?” I say.

Bassett, wearing gloves, is locked in a duel with one of the BYU runners. “Go Pilots!” the other umbrella holders shout when Bassett flies by. “Go Jared!” I shout, feeling like an insider. He doesn’t appear to notice any of us. A few places behind, neither does Yorks. I’m impressed by the economy of his form, the length of his stride—he reminds me a little of David Rudisha. On the final loop, however, Yorks is not where we’re expecting him to be. “Oh, man,” Aly says when we finally spot him, “he looks hurt.” And he does. For a moment, I consider jumping out onto the course to remind him that wherever he finishes won’t affect the outcome, that finishing is not worth risking injury, but something in his eyes makes me realize that dropping out might hurt even more.

We rush over to the track for the finish. Bassett comes in with everything he’s got. Yorks hobbles straight to the medical tent. Then, a few minutes later, over the PA system, the scores are announced. “This was a tight one,” the announcer says, “with only one point separating first and second. Taking second place, with 33 points, is BYU.”

Which means Portland has won its 33rd conference championship in 34 years. Everyone in purple goes crazy. I let the pandemonium subside before tracking down Bassett. “How does it feel?” I ask, just like a proper sportswriter.

“It’s special to go out on top,” he says.

“You were the fifth guy, right?”

“I was the fifth guy,” he says, starting to shiver. In cross-country, fifth is the final scoring position on a team. Bassett had clinched the victory. We start talking about what’s next—regionals—but he seems distracted. He keeps looking at something behind me. Eventually I turn and see Yorks, on a chair in the medical tent, with someone kneeling in front of him. Bassett’s really shivering now. “I can’t believe cross-country’s almost over,” he says.

I DON’T KNOW, though. Maybe it’s never over. My friend Dempsey has caught the running bug big-time. Hoping to inspire the rest of us out of our postsummer lethargy, he decides to host a fun run in early November. About 30 of his friends sign up to run either a half marathon, a 10K, or a 5K. A house party will follow, complete with band and a keg: instant pain relief. I grudgingly sign up for the 5K. Dempsey asks us to come up with a name for the event. Much to his chagrin, we christen it The Dempsey Dash.

Dempsey gives us about six weeks to prepare. My goal is to get in shape without feeling like I’m trying to. So I splash through the puddles of Laurelhurst Park maybe 10 or 12 times. One particularly energetic morning, I manage to convince myself that I’m running seven-minute miles. A few minutes later, a middle-aged guy floats past me. I no longer believe that I’m running seven-minute miles.

The morning of the Dash, however, I discover that I may have overtrained for the event. All the people who actually go running on a regular basis are doing the 10K or the half. Most of my competitors waited until this week to start training. I’m pretty sure none of them ran in high school, or went to state, or broke 17 minutes that one time. It occurs to me that I’m going to win. I haven’t won a race since 1995. I confide in Dempsey that I’m pretty confident. Dempsey warns me that our friend Stephen also thinks he’s going to win. “Did Stephen run in school?” I ask, noticing, as if for the first time, Stephen’s long, skinny legs.

Dempsey nods. “Shit,” I whisper.

“Is everybody here?” Dempsey asks. “Does everybody have a map?”

Everybody’s here. Everybody’s got a map. Everybody’s in the street in front of the house posing for a photo on the starting line. “TEN! NINE! EIGHT!” we shout. It’s kind of like New Year’s, with less drunkenness. Aly announces that she’s already put the starting-line photo up on Facebook. “SEVEN! SIX! FIVE!” we shout. Despite the fact that I’m laughing at Aly along with everyone else, that old prerace thing is starting to bloom inside me, that sick certainty that I am going to lose. “FOUR! THREE!” we shout. I find myself trying to remember exactly why I thought it was a good idea to start running again. “TWO!” we shout. And then I remember. “ONE!” we shout. And then for one very long second, I flash back to Coos Bay.

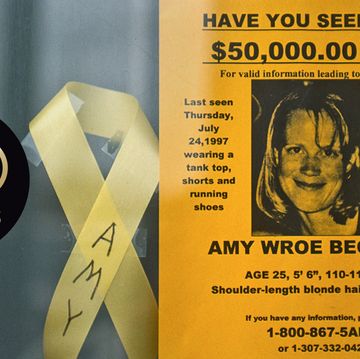

It’s the morning after the memorial run. I’ve checked out of the motel and am driving south on 101. A few miles out of town, the road to the cemetery climbs sharply to the right. There are no cars in the lot. Behind me lies one of the long, shallow fingers of the bay. Above me is his grave. I wonder if anyone else was here yesterday, when Elfriede and Linda came to visit. I really hope not. I’d like to think they had him to themselves.

His headstone is marked by a large bush. At my feet are five or six pairs of old running shoes. People have left behind flowers, finisher’s medals, race numbers, newspaper clippings. Most of the stuff looks like it’s been here a while. I’m glad to be alone.

I climb to the far edge of the cemetery, out of earshot of the headstone. I’m trying to get through to my brother but the call keeps going straight to voicemail. By the time I decide to leave a message, my voice is all throaty. I’m thinking back to something Elfriede told me yesterday, that Steve wasn’t motivated by fame. At the time, I thought she had it all wrong, that she didn’t really understand her son. But now, standing here, trying to finish this voicemail, I realize that it’s not my business to tell her who her son was. How disgusting, that I would presume to know more about him than she does. Lost in all the conjecture about Steve Prefontaine—Would he have won in ‘76? Would he have approved of Nike? Would he have kept distance running from fading from the public imagination?—is the simple fact that had he lived, his family wouldn’t have to deal with people like me.

“Dave,” I say into my phone, “I think it’s just a really sad story.”

I climb back in the car, but I’m not quite ready to return to Portland. I drive back into town and park at the end of Elrod Drive. Somewhere a few blocks behind me is his home, but it’s the trail in front of me that I’m interested in. The trees are so thick overhead that it feels like dusk when I enter the woods. The trail winds its way up a hillside. Soon the town is gone and I’m working up a sweat. I’ve got the same jeans and sneakers on as yesterday. Without really thinking about it, I bend my elbows and break into a trot. My hair lifts off my forehead. Up and up I go. I feel faster than I have any right to feel. It’s been nearly two years since my last run. Am I really doing this again?

“GO!” we shout.

Those of us running the 5K will make a loop around Alberta Park, brush the edge of Fernhill Park, then circle back to Dempsey’s. The first mile is flat, and Stephen and I run alongside each other, a stride or two behind our friend Jeff. The three of us immediately put several blocks on the rest of the field. We’re chatting about how out-of-shape we are, how weird it is to be in the lead.

“I hear you used to run,” I say to Stephen.

“I did,” he says.

“Where’d you go again?” I ask.

“Grant,” he says.

“Grant? That’s right! We’re rivals! I went to Lincoln!”

“Go Generals!” he yells.

“Go Cards!”

No one suggests taking it easy. We go through the mile in about seven minutes. I don’t have a watch, so I’m using the stopwatch function on my phone, carrying it like a baton. We start up the single hill on the route. It’s not much of a hill, but it’s enough to make a difference. The chatting gradually gives way to the sound of three men trying to do something they probably shouldn’t be trying to do. A couple out for a walk gives us a worried look. Even their dog looks kind of alarmed. But soon enough, I’m too out of breath to worry about what I look like. All I can think is, I was always good on hills. Hills are my forte. Instinctively, I take the lead. This is it. I’m making my move. For a few seconds, I feel absolutely amazing—I’m making my move!—and then I realize just how far we are from the finish.

How much this is going to hurt.

AFTER THE RACE, when the rest of us are already a couple beers in, the half marathon crew rejoins the party. Dempsey rests a damp arm on my shoulder. “The champ?” he says.

“First win in 17 years,” I say.

“Close?”

“Close doesn’t begin to describe it. I was scared the whole way. Stephen kept closing the gap, and when I’d feel him right behind me, I’d make a little surge and pretend for 15 seconds or so that I was feeling great. I totally forgot what it’s like to be in front. It’s fucking scary. You can’t just take it easy.”

“But it’s worth it, right?”

“It’s worth it right now,” I say. “We’ll see about tomorrow.” Dempsey and I do some pretend-stretching and swallow some beer. We talk about how we should get a little group together for the memorial run next September. We’ll drive down for the weekend and camp at the dunes. But I’m not quite finished discussing my race. I’d completely forgotten what it’s like to try to win. It’s making me look at things a little differently. “Do you think it was scary for Pre?” I ask.

“To be honest,” Dempsey says, “I don’t know very much about him.”

“I think maybe it was scary for him,” I say. “But that didn’t stop him from trying to do it every single time.”

“He meant a lot to you,” Dempsey says.

“I’d almost forgotten,” I say. “I got cynical about him once I stopped running. But when I was a teenager—

Dempsey refills my glass.

“You know who he was to me?” I say. “He was that crazy guy who knew how to get you to do stupid shit. You hated him in the moment, and you hated yourself for being so easily manipulated, and then afterward, when you were completely spent, so tired you couldn’t even open your eyes, he’d grab you by your shoulders and shake you around, demanding, ‘Wasn’t that great?! Wasn’t that great?!’ The finish chute at a cross-country meet, I bet even now, is filled with kids with their eyes closed, whispering to Steve Prefontaine, ‘Okay, fine, asshole. You were right.’”

Story Update · August 25, 2016

Elfriede Prefontaine passed away at the age of 88 in July 2013, just three months after this story was published. It’s now up to Pre’s sister, Linda, and step-sister, Neta, to bear his legacy. “It’s a huge responsibility that I take on gladly to keep my brother’s story alive,” says Linda. The sisters aren’t alone in their efforts. In July, city planning officials in Eugene, Oregon, applied to designate “Pre’s Rock”—the site where the runner died—as a historic city landmark in recognition of its significance to fans. A visit to Pre’s hometown of Coos Bay, likewise, remains a rite of passage for many runners. The coastal town is about 120 miles from Eugene, where the U.S. Olympic Track & Field Trials were held in July. That same month, visitors from 20 states and six countries signed the guestbook at the Prefontaine Memorial Gallery at the Coos Art Museum, according to a local newspaper. Indeed, it’s safe to say that, for those who knew him, and for those who wish they had, Pre will continue to inspire. Nike founder Phil Knight, in a New York Times op-ed published after the release of his memoir, Shoe Dog, called Pre “the soul of Nike, its winged symbol.” Writer Michael Heald says, “On a personal level I would say that this Prefontaine story—my first Runner’s World story—continues to affect my life positively. I’m still running and running races, and I’ve made my peace with a seven-minute mile feeling fast.” –Nick Weldon

Back to Top