HE WILL WAKE AT 4 A.M., as he does every weekday, except Monday. He’ll wear shorts and a T-shirt, even in the rain, unless it’s winter, when he might pull on a Gore-Tex jacket and pants. When it snows and the snow is heavy enough, he’ll stretch thin rubber sandals with metal spikes over his running shoes. He’ll grab a small canister of pepper spray. Three seasons out of the year, he’ll lace up one of his six pairs of “active” size 13 Sauconys that he keeps in a closet underneath his 100 hanging T-shirts, and in the winter he’ll wear one of his half dozen pairs of active Nikes from the same closet, because the layer of air in them doesn’t seem to compress in cold weather as much as the foam in the Sauconys. He’ll be out his front door at 4:15, back inside at 5:05. Then he’ll shower, eat a bowl of instant oatmeal, make himself a lunch of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich or pack a cup of yogurt, and leave his house in Warwick, New York, at 6:10 to drive to the train station in Harriman for the 6:42 train to Hoboken, New Jersey. The trip will take a little over an hour, and in Hoboken he’ll board a 7:55 underground train bound for Manhattan. Once there, he’ll walk 15 minutes to his office at an insurance company at Madison Avenue and 36th Street.

John Moylan is a man of habit and routine and caution, and for much of his life attention to detail has served him well. Some mornings, when he’s feeling adventurous or wild, he’ll make a little extra noise between 4 a.m. and 4:15 a.m., just to see if his wife of 30 years, Holly, will wake up. She hasn’t yet.

His running route starts outside his front door and it hasn’t varied for six years, since he and Holly and their two daughters moved from Crystal Lake, Illinois, when his then employer, Kemper Insurance, transferred him to New York City. Down Kings Highway, through the small village, up a small hill, and by the time he passes the Mobil gasoline station at the end of the first mile, he’ll know if the run will be easy or hard, and if it’s hard, he’ll remind himself to eat healthier that day, to make sure to get to sleep by 9 p.m. At one and a half miles, he might pass a gaggle of geese that like to waddle near the black granite memorial to the seven people from Warwick who died on September 11, 2001. He’ll run past one dairy farm and its herd of cows, and he’ll make mooing sounds and wonder why they never moo back. Later, he’ll pass another dairy farm and moo at those cows, who always moo back. One of life’s mysteries. He’ll run past what’s really no more than a giant puddle next to the road that he thinks of as the turtle pond, because he once saw a turtle waddling across the concrete toward the water. He’ll run four to five miles, 10 or 12 on Saturday, and on Sunday anywhere from 10 to 16. Mondays, he rests.

Moylan is by nature conservative, by profession cautious. He has been in the insurance business for 33 years and has spent much of his life calculating risk, calibrating the costs of bad planning and devastating whim. Men who worry about the future can guard against the worst sorts of accidents. Men who look ahead can avoid life’s greatest dangers. Even when running, even during the time of his life that is devoted to release and escape from daily tallies and concerns, he can’t quite escape the principles that have guided him for so long.

“What do I think about?” he says. “God, just about everything. Am I on target for my marathon goal? How am I going to pay my daughters’ college tuition? Do I have good retirement plans?”

Some days—one of life’s mysteries—he thinks of that terrible morning five years ago.

THE SIMPLE THINGS

He and one of his coworkers, Jill Steidel, had just arrived at their office on the 36th floor of the north tower at the World Trade Center in downtown Manhattan. They were carrying coffee they had picked up from the Starbucks in the building’s atrium. He had his usual—a grande-size cup of the breakfast blend, black. It was 8:46 a.m., and Moylan was standing at his window, looking west, gazing at the ferries on the Hudson River. It was one of his great pleasures, what he called “one of the simple things in life.” That’s when he felt the building shake and heard a loud “thwaaang.” He had heard longtime employees talk about the 1993 bombing in the building’s parking garage, and now he thought the building might be collapsing as a result of residual structural damage. Then he heard screaming. He was one of the fire marshals on his floor, so he rounded up his employees—there were about 25 of them—and herded them to the stairs. As a longtime runner, he checked his watch as the group entered the stairwell. It was 8:48 a.m.

The stairwell was packed, but orderly. He remembers two “nice, neat rows” of people, scared but polite. He remembers many breathing hard and sweating, wide-eyed. He remembers thinking that his experience as a runner helped him stay calm. “What was it?” someone asked. “It wasn’t a bomb,” someone else said.

The people in front of his group would sometimes stop suddenly, which made his group stop. That didn’t make sense. Neither did the smell. Moylan had been in the Air Force as a young man, and it was a familiar odor. “I thought, What the hell is jet fuel doing here?”

It took 28 minutes to get to the ground floor. Moylan left the building at 9:16 a.m. He turned to his right and looked east, just as two bodies hit the ground. He saw other bodies on the ground, realized that’s why firefighters had kept people from exiting the doors in a constant flow. He saw greasy puddles of blazing jet fuel, huge chunks of twisted metal. He saw more bodies falling. (It’s estimated that of the more than 2,500 people who died in the twin towers, 200 had jumped.)

He and the others were marshaled to the overpass that stretched over the West Side Highway and to the marina next to the Hudson River. At the marina, he looked back. People on the higher floors were waving pieces of clothing and curtains from the windows. There were helicopters—he thought there were eight or 10—circling. He could see that the helicopters couldn’t get through the fire and smoke, and he knew that the people in the windows could see it, too. He was used to synthesizing facts quickly, and it didn’t take long to comprehend the horrible calculus confronting the people in the windows: be burned alive or jump. He wondered what he would have done.

Thousands of people were on the marina. Some stared upwards. Others walked north, toward Midtown. The Kemper employees for whom Moylan was responsible had all gotten out safely; now Moylan needed to get home. The subway was shut down, as was the underground train to New Jersey, so he boarded a ferry to Hoboken. When he got to Hoboken at 9:59, he looked back, and as he did so, the south tower, which had been hit at 9:02 a.m., crumbled. The north tower, his tower, would fall at 10:28 a.m.

In Hoboken he boarded a train for home, but first he tried to call Holly and his daughters, Meredith and Erin. He had left his cell phone in his office, so he borrowed one, but it wasn’t working. Neither, he remembers, were the landlines.

He remembers the hour-long train ride to Harriman, and from there the drive to Warwick. He remembers with absolute clarity walking through his door at 4 p.m., covered in soot, smelling of fire and death. Five years later, the memory still troubles him.

“The home office had called, looking for me, which just scared my wife even more. My suit was ruined. I was reeking. I scared the living daylights out of them. My daughters especially were emotionally ruined, or disturbed…When your family thinks you’re dead and you walk in your house and surprise them…”

He stayed up all night, watching television. In the morning, he knew what he had to do. He rose from the bed where he had failed to sleep. “I wanted desperately to go out running,” he says. He just couldn’t get his shoes on.

ACCIDENTS HAPPEN

Moylan knows better than most men how accidents can shape a life. He had been working in the East Norwich, Long Island, post office in the summer of 1970 when he learned he had drawn the 11th spot in one of this country’s last drafts. He had always thought how neat it would be to fly planes, so he enrolled in the U.S. Air Force. And that’s how he got to Iceland.

There he was, in the summer of 1971, a cop’s son from East Norwich, playing softball at midnight, soaking afterward in thermal hot springs, gorging on fresh salmon, drinking beer with pretty girls who spoke another language. Forget planning. He couldn’t have dreamed that summer—”one of the best years of my life.” Pure chance. Then another one of life’s mysteries. Late one night, in April of 1972, there was a knock on his barrack’s door. It was the chaplain. Moylan’s father had died; he was only 46. After the funeral, Moylan asked his mother how she was going to hold onto the house. She told him not to worry, but he pressed. Did she need his help?

The Air Force gave him an honorable hardship discharge, and he went back to the post office, and he might still be there if his mother hadn’t insisted that he go talk to one of the leaders of the church she attended. He was an insurance executive, and he was always looking for bright young men.

So in 1973, Moylan became a company man, a trainee for Crum & Forster, a salaried student of chance and fate. Every morning, he waited for the 7 a.m. Manhattan-bound train from the station in Syosset, Long Island, and every morning he stood in the same spot and walked through the same door and sat in the same seat. And every afternoon, he did the same thing at Pennsylvania Station, when the 5:06 eastbound train pulled in. Then one afternoon, the train stopped 20 feet short of its usual spot and people pushed and shoved and Moylan’s seat was taken and he had no choice, there was only one empty seat left. He found himself sitting next to a pretty blonde dress designer from Huntington. Her name was Holly.

Accidents happen, and it’s one of life’s mysteries the effect they’ll have, and all you can do is try to control what’s controllable. And that’s how a young, married company man started running. It was 1979, and Moylan had gone from a lean, 180-pound military man to a 220-pound 28-year-old, pudgy, listless suit. He needed to do something. He had read an article about Bill Rodgers, and the New York City Marathon, and he decided that running sounded like fun.

Moylan is not a man to make a big deal out of things, and he doesn’t make a big deal about that decision. But two years later, in the spring of 1981, he ran the Long Island Marathon. He ran it in just under four hours. In the fall, he ran the New York City Marathon, and did even better, finishing in 3:51.

He cut out junk food, started eating lean meats. He woke early, ran before the sun rose. He experimented with equipment and distance and learned “to not let my mind get in front of my body. I learned that patience is a virtue.”

He wore his running shoes when he walked from the train to his office building, and he wore them when he took his midday 45-minute walks around Manhattan. He always worried that people thought he looked funny.

By 2001, by the time he was 50, he had run 14 marathons, many half-marathons, countless 10-Ks and 5-Ks. Running helped him reduce his blood pressure from 120/90 to 110/60, helped him reduce his weight from 220 to anywhere from 180 to 195, depending on where he was in his training cycle. His resting pulse is 50 now, and when he gives blood, Red Cross officials routinely question him to make sure he’s not a fainter. Running helped him cope when his mother died in 1985 at age 59, with the birth of his daughters in 1982 and 1985, with the demands of being a middle-age father and husband and provider and company man. He ran because he didn’t want to die young, as his parents had, and because it relaxed him and was part of his life. Accidents would happen, and there were some things a man couldn’t do anything about, terrible things. But with discipline and attention and will, a man could carve out a safe place, a part of life that was predictable, calming in its sameness. Half an hour or so in the early morning stillness could help a man deal with almost anything.

It was Tuesday, five years ago, the week after Labor Day, and warm for that time of year, in that part of the country. A morning like this was rare and precious. It would be a good run. It felt like it would be a good day. At the Mobil station, Moylan picked up his pace.

He ran past the cows and the geese and the turtle pond. He thought about his retirement fund, even though he had many years to go before needing it. He worried about his daughters’ college tuition, even though he had been saving for years. He wondered if he would run as swiftly as he wanted to in the New York City Marathon, even though it was still two months away. He was back at home at 5:05 a.m., and showered and had his instant oatmeal and caught his train and met Jill Steidel at Starbucks, and they rode the elevator up to the 36th floor, and less than a minute later, he felt the building shake. And the next day, he couldn’t get his running shoes on. He couldn’t put them on the next day, either. He woke at four each day, got out of bed, thought about running, got his shoes out of the closet, then put them back. Then he would sit on the couch and watch television and his mind would drift. He thought about a framed photograph he had left on his office desk. Holly had taken it, and it showed Moylan and Meredith and Erin at a Yankees game in July. It was cap day, and they were all wearing Yankees caps. He doubted he could ever find the negative. Then he thought about all the people who didn’t get to say goodbye to their families.

Friday, September 14, was his 26th wedding anniversary, and on that morning he got dressed and he laced up his Sauconys, and he opened up his front door. He looked outside, into the darkness. Then he closed the door and went back inside.

THE FUNNY SENSE

It is late spring, nearly five years later, and he is looking at the space where the World Trade Center once stood. It is the first time he has been back here. He says he’s surprised that the footprints of the two towers aren’t more clearly marked. He’s disappointed that the twisted cross of metal that became the focus of so many Christians is no longer on the site.

And Moylans inability to go for his normal run.

“When I came out,” he says, “it was on this level. I had a view—right in this area, the bodies were already falling. I could look up and see the people hanging out the windows. The news footage, you just saw smoke. From down here, it was like looking up from the bottom of a grill. I remember seeing how ungodly hot it was—there was an orange glow.”

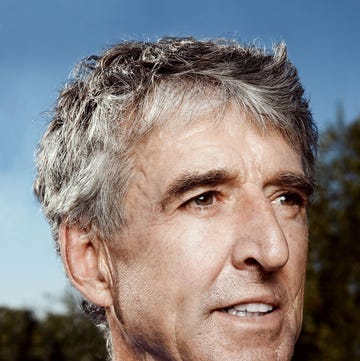

Moylan is a handsome man, square-jawed, grey-haired, hazel-eyed. He is 6 feet, a solid 190, on his way, he says, back to 180. He wears a blue suit and a pin of the twin towers and an American flag, and he looks like a soap-opera actor or the Air Force pilot he might have been. If this were a different place, he might appear to be just a tourist searching the New York City skyline for wonders.

He turns from the ghost buildings and looks toward the bank of the river, at the benches where he used to unpack his peanut butter and jelly sandwiches or his yogurt cup. “This place was my luxury suite for lunch in the summertime…I used to come out here on the bench and just dream.”

In the weeks after the attack, Moylan studied a New York Times article about the sequence of events and realized that had he taken two or three minutes longer to get his coffee with Steidel at Starbucks, he still would have been in the elevator on the way to his office when the plane hit and he wouldn’t have survived.

Moylan turns back east, away from the water. Reflection can be healing, but he has work to do. He needs to get back to his office, five miles north in Midtown. “The funny sense that I get being here,” he says, “is, life goes on. It’s continuing.”

“I DON’T REMEMBER THAT”

It is early spring, dusk in Orange County, New York, and Moylan and Holly and their oldest daughter, Meredith, are driving the back roads of Warwick. Holly points out a place where George Washington slept. Meredith points out a dairy farm and creamery. We drive through the gaggle of geese and past the granite memorial to the people from Warwick who died on 9/11.

At dinner, we talk about past races, about what running meant to Moylan before 9/11. Meredith talks about watching her father finish one marathon on an ocean boardwalk, yelling, “That’s my Daddy and he loves me,” and years later joining him in center field of San Francisco’s Candlestick Park for the end of a 5K run. Holly and Meredith talk about how they enjoy staying up watching The Gilmore Girls and chatting when John goes to sleep. Holly wonders aloud why her husband—or any man—needs 100 T-shirts, and Moylan speaks mournfully of the “boxes and boxes” of his T-shirts she donated to charity.

I ask Holly and Meredith how long it took for them to get over the shock of seeing Moylan walk in the door, how they dealt with the hours of uncertainty.

“I wasn’t uncertain,” Holly says. “When we were watching the coverage on television, I told Meredith, ‘Dad will be fine. He’s a runner and he’ll run right out of there. Besides, he called us from Hoboken, before he got on the train.’”

Moylan blinks, shakes his head.

“No, I didn’t call you. I didn’t have my phone.”

“You definitely called us,” Holly says. “You borrowed a phone and called us to let us know you were coming home.”

Moylan blinks again. “I don’t remember that,” he says.

“Yeah, Dad,” Meredith says, “you called from Hoboken. To let us know you were alright.”

STORYTELLERS

Harold Kudler, M.D., is an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Duke University and a nationally recognized expert on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He hears part of John Moylan’s post 9/11 story and says, “It’s quite common for people in the middle of an acute stress response to have disassociative phenomena.”

To Dr. Kudler, Moylan’s elaborate memory of his family being traumatized as a result of not hearing from him makes psychological sense. “Sometimes,” Dr. Kudler says, “the effort to create meaning and to create a meaningful narrative about what has happened to you actually becomes more important than the actual memory and might replace it. This story about coming home as a ghost and having everyone else scared might be a way to say, ‘Boy, was I scared. I felt like a ghost in my own life. I wasn’t even sure when I got home if I had survived that.’”

Moylan’s responses during and after the attacks—his vivid recollection of details, his construction of false memories, his nightmares, his long avoidance of the WTC site, his difficulty running afterward—are entirely consistent with symptoms exhibited by people facing extreme trauma, even the most resilient people, according to Dr. Kudler.

“There’s a tendency to medicalize or pathologize responses,” Dr. Kudler says. “It might be better to think that here’s someone who is faced with a new challenge that’s so radically different than the one he faced a few days earlier.

“Think of it like mourning. When you’re bereaved, you wouldn’t be able to invest in yourself, because you’d feel overwhelmed, and you’d sort of lose your center. For a while you wouldn’t be able to do the things that reminded you of who you were, of the thing you did for yourself.”

And Moylan’s inability to go for his normal run?

“Running for him was something he did for himself, was important to him, and he made a point of always doing this regardless of anything else. Great exercise, recreational, self-affirming. But in the context of the disaster, when people are overwhelmed and filled with doubt, it’s easy to see why someone wouldn’t do those self-affirming things.

“And if he was angry, that anger may have drowned out his capacity to enjoy a simple pleasure like running, and take that simple time for himself. That anger could have drowned out a lot of those normal, good impulses.”

A CAREFUL MAN.

“He nailed me,” he says.

PERSPECTIVE

He would wake in the middle of the night, certain that his house was under attack. He would dream that he was up in a tower and flames were licking at him. He would dream of having to make a terrible choice but not knowing what to do. He would dream of dying, “that I went through what those people went through.” Noises startled him. “He was restless and jumpy and things would frighten him,” Holly says. “If we were out somewhere and a child cried out, he’d jump, he’d be scared.”

During the day, he thought of the people who had died. “I couldn’t rationalize what had happened. People in the normal course of living, going to work, murdered. I thought about how they never got to say goodbye to anyone. I thought about my family, and about facing a decision to burn to death or to jump.”

Every morning in the weeks after 9/11, he would get up and he would plan to run. But he never made it outside. He would make coffee, and sit on the couch, and sometimes watch television, and have his oatmeal, and when it was time to take his shower and catch his train, that’s what he would do.

He couldn’t stop thinking about chance, and fate, and wondering why he had survived.

At his company’s insistence, he had two conversations with Red Cross officials, once in a group, once alone. He talked about how angry he was that there had been an attack. He talked about how angry he was that he had survived while others had died. He talked about how angry he was that he couldn’t run. “And that about covers it,” he says.

He reported for work on September 13, in Kemper’s New Jersey office. The company assured Moylan and his coworkers that they would be reassigned to a building in midtown Manhattan, on a lower floor. The morning they reported for work there, on the 10th floor of Rockefeller Center, was the day authorities discovered an envelope filled with anthrax addressed to Tom Brokaw in the same building. Some of the Kemper employees left and never came back. Moylan stayed.

The nightmares continued. He kept jumping at the slightest noise. But Holly didn’t say anything. “We had talked about counseling,” she says, “and he just said, ‘Let me see how things go.’” He knew that running would help him get over all his problems. So he got up every day, ready to run. But he couldn’t do it.

Then one day, he could. Just like that. One of life’s mysteries.

There were no grand pronouncements before he went to bed the night before, no stirring speeches at dinner. He was still angry. He was still scared. He still thought about the falling bodies. But on Columbus Day, almost exactly a month after the attack, he managed to get his shoes on, and to get out the door. He made it four miles, and every step was difficult. His legs were heavy. He had trouble breathing. But he made it.

His first race was a half-marathon in Pennsylvania the next April. It was a clear day, warm, “almost like September 11,” he says. “I remember that for the first time in a long time, I smelled grass, could smell flowers.”

A few months later, in October, at a half-marathon not far from his home, he happened to overhear one of the runners mention that he was a firefighter. Moylan approached him. “He said he wasn’t there, but he knew people who were. I told him I was in tower one. We both had similar feelings…about losing people. It was the first time I had verification that I wasn’t the only person who felt like I did.”

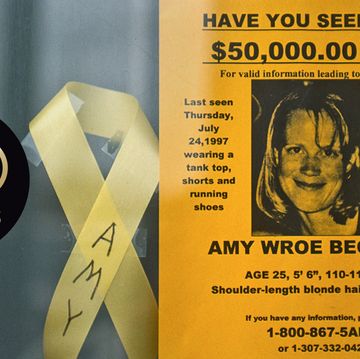

How the feature appeared in the September 2006 issue.

He ran the New York City Marathon in 2002 and 2003. He ran more marathons, more half-marathons. The nightmares faded away, as did his preoccupation with death and the randomness of fate. (He still jumps at the slightest noise, something he never did before 9/11.) Three years ago, Todd Jennings, who lived near Moylan and who had just started running, spotted Moylan on the train “in his gray flannel suit and running shoes.” Eventually, they started talking. About training regimens, and race strategy, and running in general. “No,” Jennings says, “we never talked about 9/11.”

Moylan and Jennings traveled to the Boilermaker 15K in Utica, New York, in 2005, and the night before the race they went out for a pasta dinner. “He told me,” Jennings says, “‘I want to be remembered on my tombstone as a runner. Running is who I am.’”

There are things you can’t control, no matter how much you worry and plan. Terrible things happen, and there’s nothing you can do to stop them. Those are lessons that will change a man. For better or for worse.

After 18 years, Moylan left Kemper Insurance in 2002 to go to work for Greater New York Insurance. He doesn’t worry about what others think about his blue suit/white running shoes combination in Midtown anymore. He ran a 3:22 marathon in 1982 and a 4:50 marathon in 2003. He still wants to get back to a four-hour time, “but I don’t worry so much about time anymore.” He is training for this fall’s New York City Marathon. He still thinks about retirement and paying for his daughters’ education, but it doesn’t eat at him quite as much as it used to. He still calculates risk and calibrates the likelihood of disaster and does his best to protect himself and his family, but he knows there are some things beyond a man’s control, and to worry about them is to waste precious energy.

When he finds himself irritated or impatient, he thinks of a terrible choice he never had to make, and he is grateful. Every morning, as he steps out his door, he is grateful.

“I told my wife, I should have a new birthday,” Moylan says. “My new life started on 9/11. The fact that I survived is a gift. I know quite a few people who didn’t. I made a promise to myself. I was going to live differently.” He tries not to dwell on the past, or to look too very far into the future. But he has made one promise to himself. “Yeah, I’m going to go back to Iceland sometime. That’s a plan now.”

THE HILLS BEYOND

Weekends, he treats himself. Friday and Saturday nights, he soaks a pot of steel-cut oats in water so he can have homemade oatmeal after his runs. He sleeps till 5:30, has a cup of coffee, “my luxury,” and dawdles for a full hour before he heads out the door. September 11 falls on a Monday this year, so he won’t run. But the day before, he’ll step out of his front door just as the sun rises above Warwick. He’ll pass the Mobil station and the silent cows and the mooing cows, but that day he’ll go at least 15 miles, so there will be other sights, too. He’ll run by the VFW hall where the old men always wave and the fire station in town where the guys always have a nice word to say. He might see a deer, or a porcupine, or even a bear. At mile seven, he’ll run by a house where a snarling rottweiler is tied to a tree, and he’ll grip his pepper spray a little more tightly.

Just past that house, Moylan will ascend a gentle hill, heading east, and no matter how hard the run, no matter how he slept the night before or how he’s feeling, as he crests the little hill, he’ll slow down. It’s his favorite spot on the weekend run—his favorite spot of any of his runs. It’s just a little hummock, but when a man reaches it, he can turn to the right and look south, and he can see an entire valley stretching before him, and beyond that valley, forests and hills all the way to the horizon. He will still have another seven miles to go, and then his homemade oatmeal, with the apples and bananas and raisins and cinnamon he allows himself on weekends. Then on Monday he’ll think again about the day that changed his life, and on the day after that he’ll catch the 6:42 train to Hoboken, and on the day after that he’ll do it again. Or not. Who can really predict what will happen to a man, even a careful man, a man who takes precautions? That’s another of life’s mysteries.

Moylan will allow himself to walk a little bit on Sunday at the top of the gentle rise, to linger, to look at the valley and the forests and the looming hills beyond. He loves this spot.

“It’s a nice place to get perspective,” he says.

Story Update · September 8, 2016

John Moylan, now 64, still runs every weekday morning, leaving his house in Warwick, New York, at about 4:30 a.m. and returning by 5:30 a.m. He still sleeps in on weekends before heading out for his long runs. “For the record,” he says, “I still talk to the cows, too.” He hasn’t run a marathon since 2011, but he has become an avid half marathon runner and plans on finishing six of them by the end of the year. The Iceland trip is coming, too; next August, he and his wife, Holly, plan to travel to Reykjavik so that he can run the local half there. Their daughters are grown; Meredith is a school psychologist and is married with a 1-year-old son, and Erin is a chef in upstate New York. John unexpectedly lost his insurance job last March and now works part-time in a family-owned hardware store “learning to do all kinds of weird stuff I’ve never tried before,” he says. Noises still startle him; a few weeks ago a shelf fell over at a store and he experienced “that heart in the throat kind of thing.” For the most part, though, his symptoms have improved, and he says he isn’t bothered when the date 9/11 approaches. He took his family to visit the National September 11 Memorial last summer following the opening of One World Trade Center. “I was able to show them the footprint of the building I was in, where I came out,” he says. “It helped me a little bit to go back.” The volume of letters he received from readers after this story, he says, “was an unexpected gift, and I tried to answer as many as I could.” As for writer Steve Friedman, he was moved by John’s “slow awakening to what this trauma had done to him, and how it led him to reflect on his life, look forward and, like all of us need to do, really appreciate the quiet moments in his life, and have gratitude for things.” –Nick Weldon

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below Its a nice place to get perspective, he says, the Washington Post, Best Folding Treadmills, New York magazine, Bicycling, Runner’s World and many other publications.