THERE'S A STORY ALL ETHIOPIA TREASURES, in which I learned I played a bit part. It’s how the country’s primal champion, Abebe Bikila, having won the 1960 Rome Olympic Marathon barefoot (symbolically avenging Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in the 1930s), and having won the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Marathon in a world record, set out in the thin air of Mexico City in 1968 to win his third gold medal in a row.

Then 24, green and idolatrous, I ran at Bikila’s side in the early miles, through a claustrophobic gauntlet of screaming, clutching Mejicanos locos. Bikila, protecting his line before a turn, even gave me an elbow. I wanted to tell him that there was no way I’d ever drive him into that crowd, but I knew no Amharic. He had tape above one knee.

Any Ethiopian child can tell you that Bikila was running hurt. After 10 miles, he turned and beckoned to an ebony wraith of a teammate, Mamo Wolde, the 10,000-meter silver medalist and a fellow officer in Emperor Haile Selassie’s palace guard. Wolde wove through the pack to Bikila’s side. Thirty-four years later, I would learn what they said.

“Lieutenant Wolde.”

“Captain Bikila.”

“I’m not finishing this race.”

“Sorry, sir.”

“DAA Industry Opt Out.”

“Master the Half.”

“Don’t let me down.”

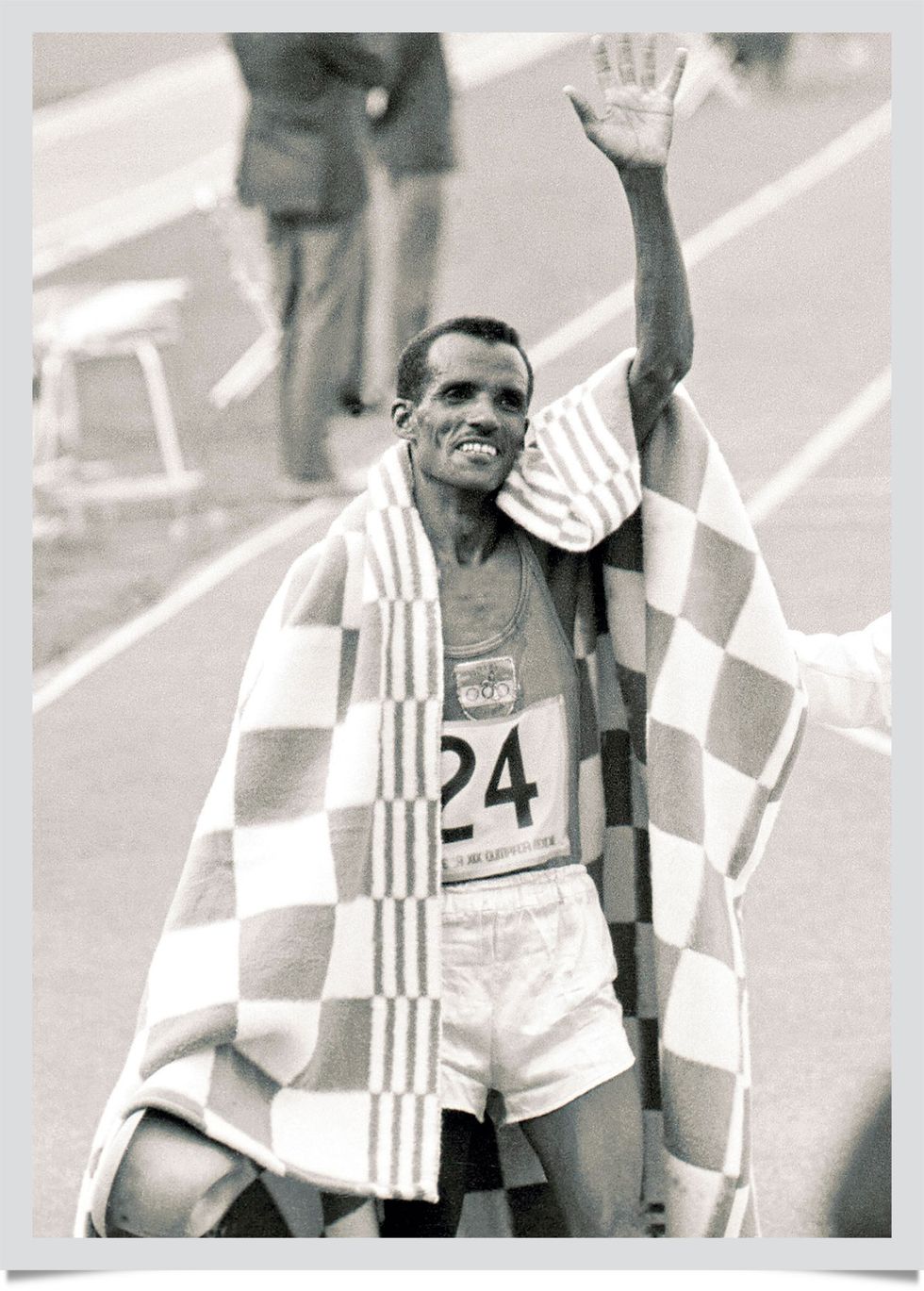

Wolde, thinking some runners were out of sight ahead, took off. None was, but until the tape touched his chest, he couldn’t be sure. He took the gold medal in 2:20:27 by a masterful three minutes.

I got blisters. I’d wrapped our trainer’s new “breathable” adhesive tape around the balls of my feet, where it came unstuck and rolled up into ridges of fire. I sat down in Chapultapec Park, took off my shoes and ripped off the tape—and my skin. I got my shoes back on, hobbled until I bled out and went numb, and finished 14th in 2:29:50.

Thus I was in the stadium tunnel when Abebe Bikila emerged from an ambulance. He caught Wolde’s eye, came to attention and saluted. Wolde, mission accomplished, crisply returned it. Wolde’s victory meant his country hadn’t produced a lone prodigy, but a succession. Wolde had made the marathon Ethiopia’s own.

Wolde went home, had his portrait enshrined among the Olympic rings atop his national stadium, and eventually would inspire Olympic champions Miruts (“Yifter the Shifter”) Yifter, Derartu Tulu, Fatuma Roba, Gezahegne Abera, and Haile Gebrselassie. The tale of Captain Bikila’s order to the good soldier Wolde became legend in Ethiopia, but I didn’t hear about it until April of 2002, when Wolde recalled I was one of the runners he passed to reach Bikila’s ear. What took so long? A simple transaction of the champion being made to rot in Ethiopian Central Prison for nine years.

You are quick to ask why. We’ll get to that, to Wolde’s great purgation, but let’s linger with him as long as we can back before the fall, before he was overtaken by the monumental anguish of his nation.

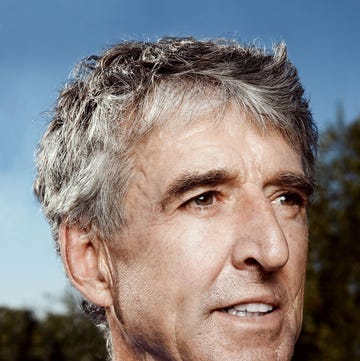

In the Munich Olympic Marathon in 1972, Wolde and I ran almost stride for stride. With five miles to go we were dueling for second, a minute behind Frank Shorter. Wolde was as soft of foot and breath as an Abyssinian cat. The only way I knew he was there was that distinguished widow’s peak bobbing at my shoulder. Occasionally our shoes brushed. “Sorry,” Wolde said each time.

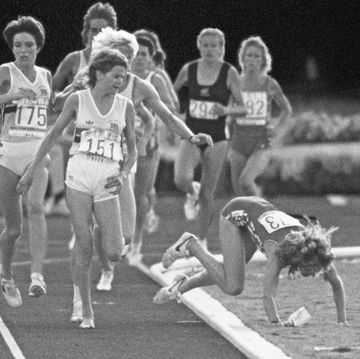

On a rough path in the English Garden, a cramp shot up the back of my right leg. Wolde watched me slow and grab my hamstring. He ran on. Then he turned and gave me a look I would never forget. His face filled with regret. It was as if he were saying this is all wrong, we were supposed to race together, and the stronger take the silver and the other the bronze. Instead, Belgium’s Karel Lismont caught us both and finished second. Wolde took the bronze. I followed in fourth, 30 seconds behind.

Shorter, stunned at his triumph, embraced me. “I thought at least I had bronze,” I croaked. “Wolde took my bronze.”

Then Wolde and I shook hands, departed the terror-stricken Munich Olympics, and returned to absurdly opposite worlds.

MAMO WOLDE RETURNED TO ADDIS ABABA, was promoted to captain, and promised a nice house. He never got it, because in November of 1974, Emperor Haile Selassie, age 83, was suffocated in his bedchamber, and his 60 top ministers, admirals, and generals were lined up against a prison wall and machine-gunned. For the next 17 years, a fanatic paranoid named Mengistu Haile Mariam changed Ethiopia from a feudal empire to a Marxist dictatorship known as the Dergue (Amharic for committee). Revolutionary Guards killed tens of thousands suspected of disloyalty. To claim the body of a loved one, a family had to reimburse the government for the bullets used in the execution. More holes meant more revenue, so death squads observed a two-bullet minimum.

Wolde, being Imperial staff, seemed in mortal danger. His Olympic and many championship medals saved him. He was ordered to take a lowly position in a local kebele, a sort of neighborhood council that Dergue officials used to spy on, detain, or torture counter-revolutionaries. He married Aymalem Beru, and in 1976 they had a son, Samuel. Aymalem died in 1987, and 2 years later, Wolde married young, adoring Aberash Semhate. They had two children, Adiss Alem Mamo and Tabor Mamo.

In 1991, the Dergue was overthrown by the forces of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front. The new government caught 2,000 suspected authors of the Red Terror and created a special prosecutor’s office to try them. Wolde was caught up in this sweep and locked up in Ethiopian Central Prison.

Wolde sat for three years without the western world’s notice. Then in 1995, Amnesty International reported that he had been imprisoned without even being charged with a crime. Amnesty appealed to the prosecutor to either charge or release him. Ethiopia did neither, refusing even to say what he was suspected of. When the International Olympic Committee (IOC) demanded an explanation, it was told to back off and “await the verdict of the court.”

I remember Shorter, a friend and a lawyer, wondering just how well we knew Wolde. I felt we knew enough. A gold medal doesn’t guarantee moral integrity, but what is more basic to the Olympics than forsaking violence? Ideals were involved here. The only way to know was to go find out.

An indispensable ally was 1972 Olympic 800-meter bronze medalist Mike Boit, who was then Kenya’s sports commissioner. He urged me to come down to Nairobi, where he got me an Ethiopian tourist visa. And so, on a rainy day in August 1995, the photographer Antonin Kratochvil and I landed in Addis Ababa.

First, we called the special prosecutor’s office. Spokesman Abraham Tsegaye blandly said Wolde was going to be charged with “taking part in a criminal act, a killing.”

I went queasy. I had come all this way on the strength of a backward glance. Suddenly it seemed childishly sentimental.

“Did Mamo Wolde have access to a lawyer?”

“Other Hearst Subscriptions.”

“If I was detained for three years without charge, I’d sure have a lawyer.”

“Well, in your country, every time you shake hands with someone, you need a lawyer. In Ethiopia it’s not such a way.”

He said he had no authority to let me visit Wolde, and hung up. Kratochvil took a look at my waxen face and asked a question that turned everything around. “Does Mamo have a wife?”

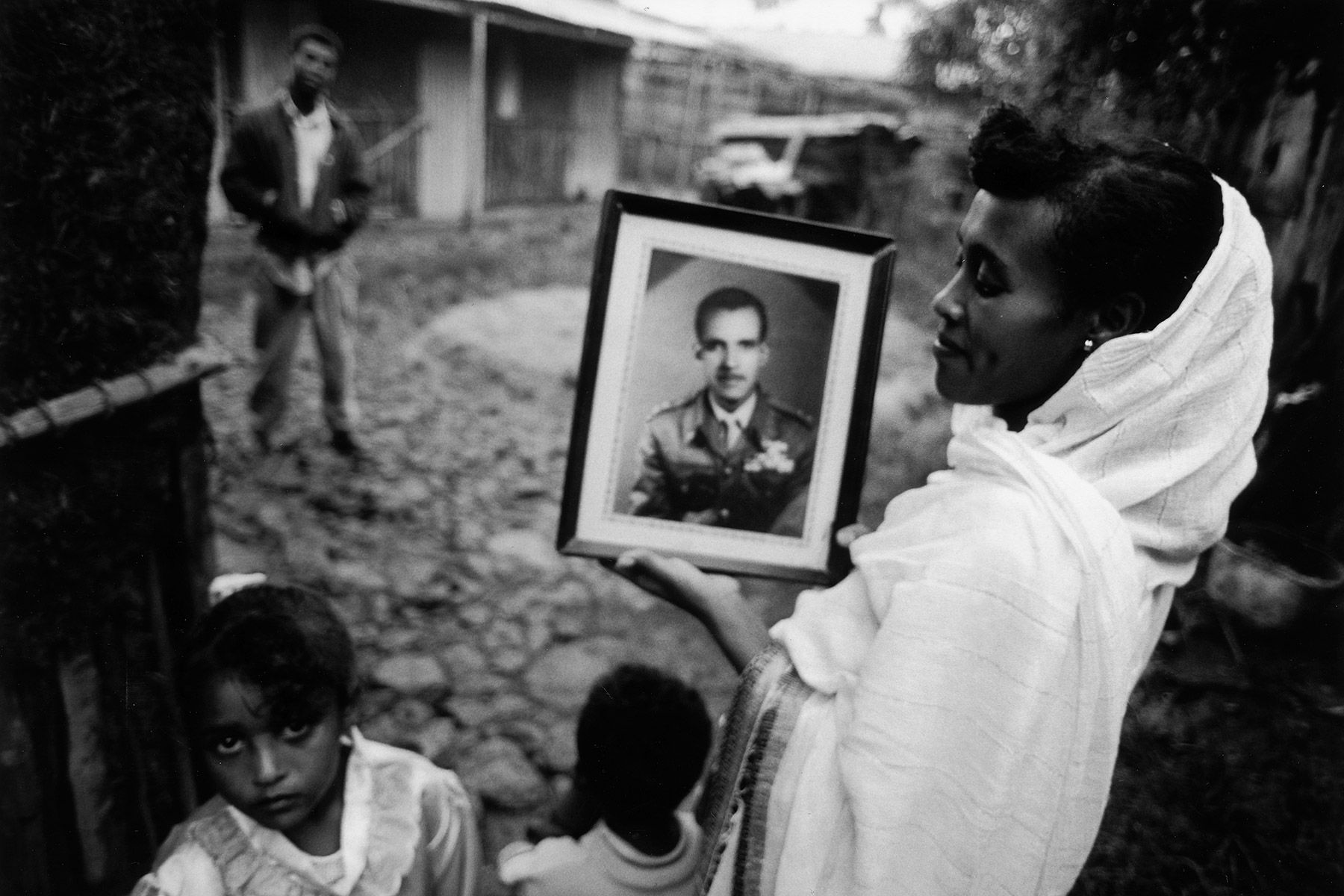

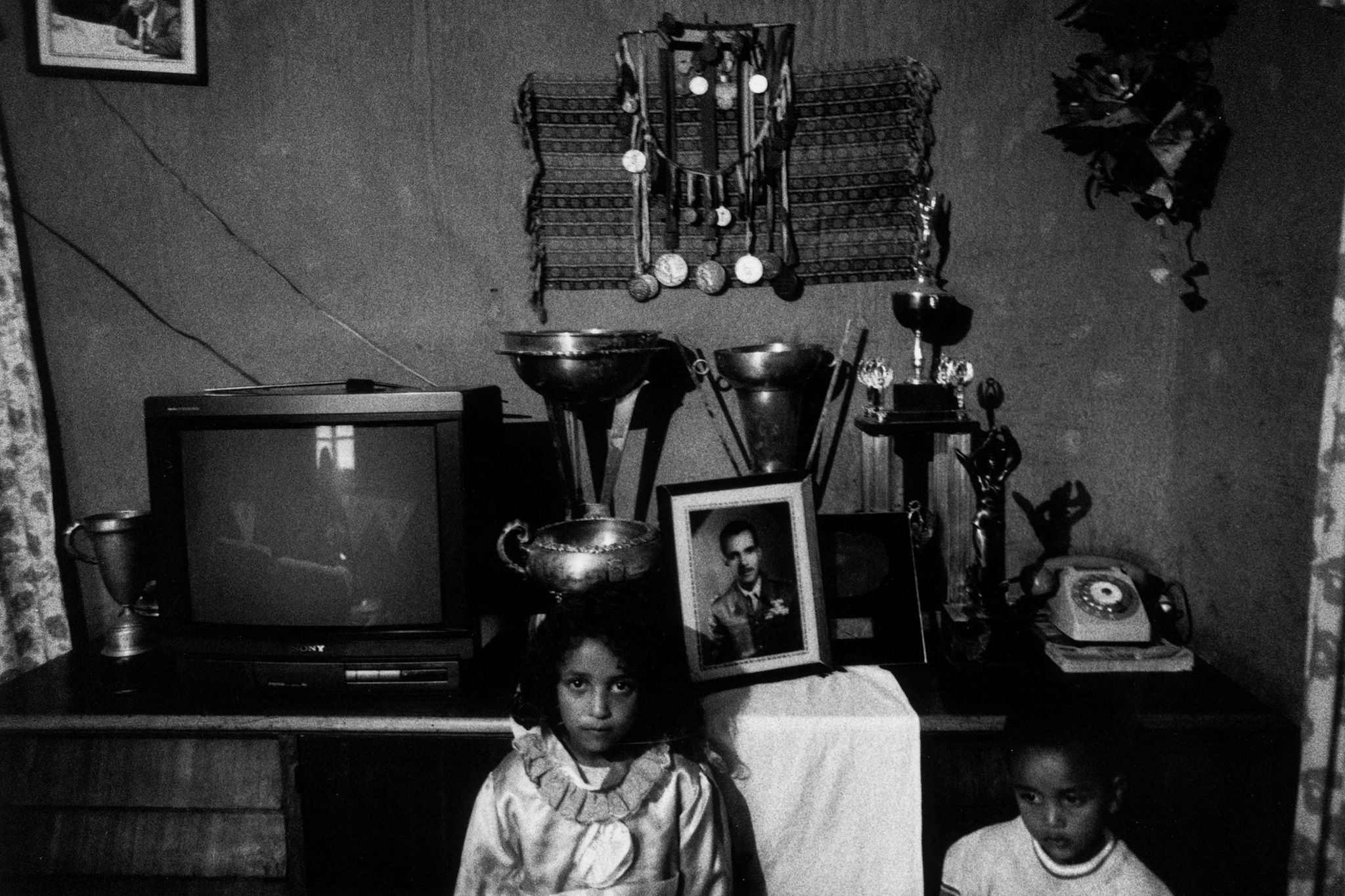

Did he ever. Slender, doe-eyed, and resolute, Aberash Wolde-Semhate, then 24, welcomed us into their mud and stick home off a rocky lane, behind a sheet-metal wall. Son Tabor, then 3, gave me a brave, cold, trembling little handshake. Adiss Alem, Mamo’s 5-year-old daughter, showed us his gold and silver medals from Mexico City.

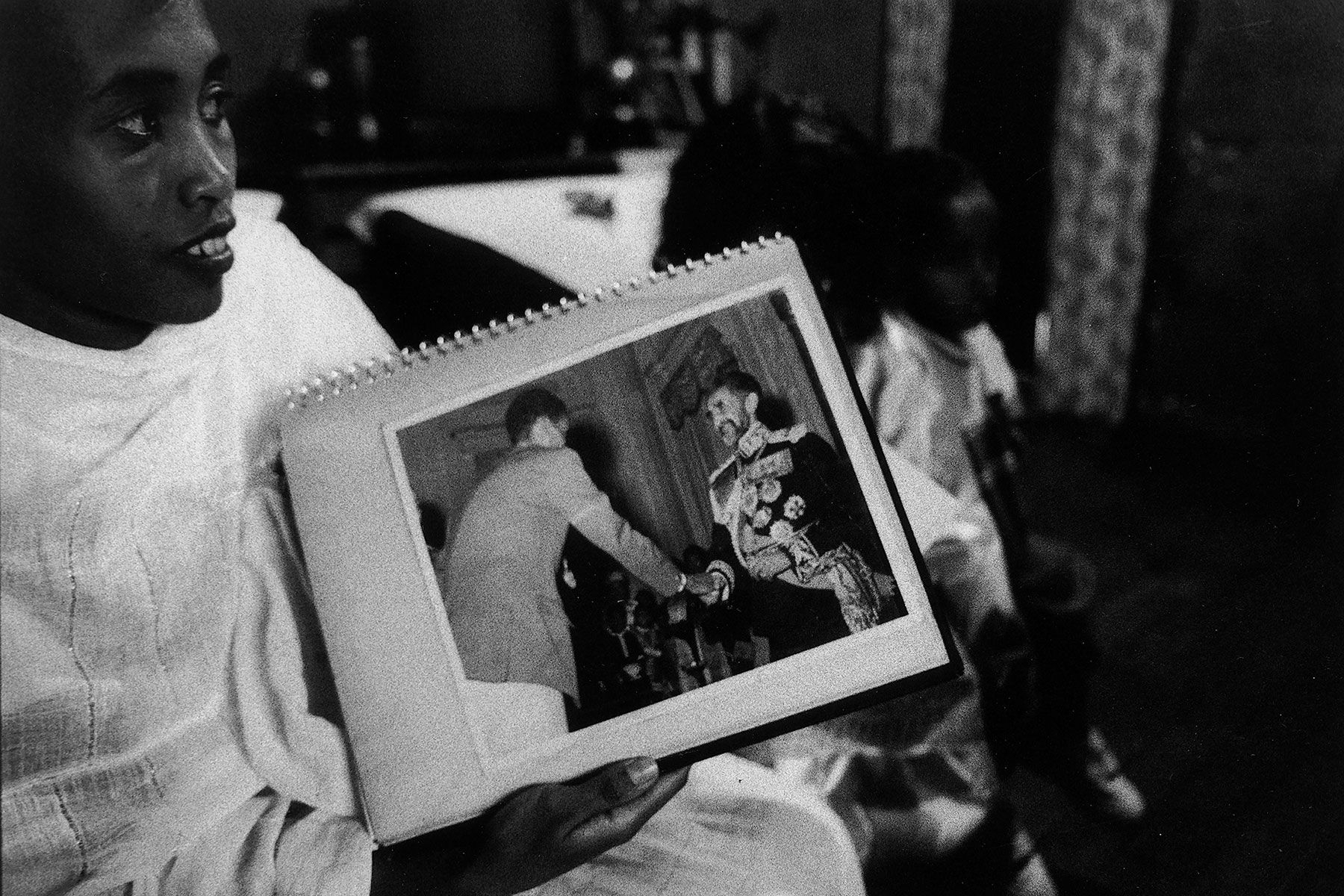

The wood floors were smooth and clean. Frankincense was in the air. Aberash poured us glasses of home-brewed beer and apologized for Wolde not being able to welcome us himself. We looked at a photo album and she sketched his history. He was born in 1932 in Ada, south of Addis Ababa, and was of the Oromo tribe. She had met him when she was 17 after his first wife died. “When I was in school, I ran a little, not seriously,” she said. “But I read about them both, our heroes, Abebe Bikila and Mamo.”

When asked, Aberash explained that Wolde was being framed. On a night in 1978, Wolde had been ordered by a top official to put on his uniform and go to a nightclub. At the club, Aberash said, he saw a group of officials with a teenage boy, hands tied behind his back, who might have been in a youth group that fought the Dergue. The officials shot the boy, then ordered Wolde to shoot the body again (the ghoulish two-bullet policy). According to Aberash, lots of people saw him purposely miss. At a hearing in 1992, many witnesses testified that Mamo hadn’t killed anyone. “Only one accused him,” said Aberash. “The official who shot the boy wants to blame Mamo to save himself. The prosecutors say they have to keep him in detention until they bring charges, but they never do.”

Meanwhile, he’d had bronchitis, hearing loss, and liver problems. Prison meals were terrible, but families were allowed to bring in food. Aberash suggested we come along for a visit.

THE APTLY NICKNAMED END OF THE WORLD PRISON was 10 blocks of post-apocalyptic depression. Rusty metal walls surrounded cement barns. In the shelter of a crumbling plaster watchtower, guards lounged in thin blue overcoats, their eyes locking instantly on us, the faranjoch, the foreigners. We joined perhaps 200 visitors in an open shed. But when we moved with Aberash toward the gate, Kratochvil’s camera was seen, and we were encircled by guards yelling that foreigners were never allowed in a prison. It was a national security offense. One guard, a man with a crippled hand, kept shouting we were cunning foreigners and that it was their duty to ignore everything we said and arrest us. We were ordered through the gate and put on a bench in the courtyard as higher authority was summoned. “Now we are detained,” said Kratochvil.

THE ENDURING WIFE.

We waited six hours, the man with the crippled hand whining ever more hysterically for our heads. They kept asking for our passports, to prove who we were. We’d left them at our hotel. Finally, we were given an escort there, a huge armored vehicle with six guards. You should have seen the face of the Hilton doorman when we all pulled in. I diverted the officers, while Kratochvil went to his room and flushed his film of the prison. A Major Neguesse confiscated our passports, and said, ominously, we would talk the next day.

The next morning, we didn’t wait. We went to the dreaded Ministry of Internal Affairs and threw ourselves on the mercy of its chief, a Ms. Mahete, a sour, angular, Tigrayan woman in a red dress. When our interpreter said I had run against Wolde in the Olympics, Mahete’s expression softened. She held up a hand, made a call, and dictated a letter. In a stroke of impossible luck, we had permission to visit Wolde.

At the prison we held up the letter like a cross before a vampire. The gate rolled open. The guards who had terrified us before shrank back against the walls. Major Neguesse begged to be forgiven. We were led down a rocky path toward a two-story building. Guards were coming down a staircase. Among them was a slender man dressed in a green-and-white sweater, and with a distinguished widow’s peak. We fought through our guards, and embraced on the steps. He was bony but warm, strong, and excited.

“It all comes back,” he said. “You had a goatee. Oh, thank you from my family for this! Remember me to the Olympic brothers.”

“You are remembered,” I said, and poured out the good wishes of the International Olympic Committee, including a standing invitation to run or be grand marshal of the Honolulu Marathon, in Hawaii, where I now live.

Wolde, thunderstruck, said, “These are words from God.”

We had maybe eight minutes together. Then he grabbed my forearms. “It restores my soul,” he said. “It is something I can feel in my body, that people outside the country remember.” They led him back upstairs.

Watching him go, I thought of what a slender thread had brought me there. But this time it was my turn to look back and cry out that this was wrong, this isn’t the way things should be happening.

AFTER THE 1995 TRIP, I WROTE ABOUT WOLDE’S PLIGHT in Sports Illustrated. As a result, that Christmas cemented my faith in human nature. Every mail brought copies of letters people had sent to the prosecutor, reminding him that justice delayed is justice denied. Schools and churches adopted Wolde in letter-writing campaigns. Athletes United for Peace, headed by Olympic long jumper Dr. Phil Shinnick and former 49ers quarterback Guy Benjamin, flooded the United Nation’s Human Rights Commission with appeals, as did the National Council of Churches.

The most unexpectedly galvanized was Bill Toomey, the 1968 Olympic decathlon champion. Toomey has never been accused of taking life too seriously, but something clicked. As president of the Association of U.S. Olympians, Toomey recruited two-time 800-meter Olympic champion Mal Whitfield (who had coached Wolde in Ethiopia) and former Assistant Commerce Secretary Carlos Campbell to urge the U.S. State Department to press for Wolde’s release on bail.

Toomey then postponed his honeymoon, went to Switzerland, and hit up IOC president Juan Antonio Samaranch for help. Samaranch made Toomey the IOC point man on the Wolde case, gave him a check to take to Aberash, and wrote a letter appealing for Wolde’s freedom and inviting him to be a guest of the IOC at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics.

Toomey ran with it, stopping in Nairobi to pick up 1968 Olympic 1500-meter champion Kip Keino, arguably Africa’s greatest sporting ambassador. In May of 1996, they descended upon Addis Ababa. Toomey called to report.

“The minister of justice was almost in tears at the sight of Kip Keino in his office,” Toomey said. “And Kip set it up beautifully. He said, ‘In three months, 3 billion people are going to watch the Atlanta Olympics. It’s the 100th anniversary of the modern marathon, and they’re going to see the great contributions Ethiopian runners have made. And then they’re going to see the misery of Mamo Wolde.’ That had an effect. They said they’d try to let him out for a day or two. I said, ‘The Olympics are 16 days.’

“We got 35 minutes with Mamo in prison. What a nice, humble person! Kip was reliving races with Mamo in Europe and Mexico. Everyone there was moved.”

Over the next few months, the IOC reaffirmed its invitation to fly Wolde to Atlanta, and the reigning Olympic women’s 10,000 meter champion, Derartu Tulu, and the rest of the Ethiopian team bravely asked for his release. Wolde began to allow himself to hope. The Olympic offer seemed to resurrect ekecheiria, the mythical Greek Olympic truce under which warriors laid down their arms on battlefields and traveled to the sacred contests of Olympia for 1,200 years.

Unfortunately, that cut no ice with Ethiopia’s independent prosecutor, Girma Wakjira. “We know Mamo is a hero of the land,” he said. “But how would authorities say, ‘Okay, Mamo, we shall prosecute the rest of the people but because you are a hero you can go to Atlanta?’” Wakjira said he would prove Wolde was “head of the Revolutionary Guard in Addis Ababa’s Area 16,” and involved with the execution of 14 young people in late 1978 or early 1979.

Wolde neared despair. “My lowest point,” he would say later, “was when the prosecutor threw all the Olympic appeals in the dump.” He was 64, with liver and lung problems, in a country where life expectancy for men was 46. “My days are numbered,” he said. “I hope the world will educate my children.”

The Atlanta Games took place without him. Ethiopia’s Haile Gebrselassie won the 10,000 and Fatuma Roba the women’s marathon. And a powerful NBC report showed Wolde racing in Munich and my trek to his home. The last images were of Aberash and the children waiting outside that dismal, decaying prison.

In Atlanta, Billy Mills, the Tokyo Olympic 10,000-meter champion, suggested we sign an Olympic flag for Wolde. He, Toomey, Shorter, Whitfield, Ralph Boston, Willie Davenport, Rafer Johnson, John Naber, Andrea Mead Lawrence, Wyomia Tyus, and I, among many others, covered the white cloth. When Aberash and the U.S. ambassador to Ethiopia, David Shinn, took it to the prison, the wardens were so impressed, they set up a tea party in the yard for the presentation. “It was ecstasy, it was rejoicing,” Wolde would recall. “There were 500 other detainees there, many who’d been government dignitaries and university presidents. When Mr. Shinn held up that flag, there was a cheer from them all.”

One Sunday after the Olympics, Wolde stretched to take Aberash’s hand through the double fence at the prison. He said the only reason he was alive to receive invitations to marathons was her tireless struggle to bring him food and news, and the sight of his kids growing up safe and strong. “I take this oath,” he told her. “When I get out of here, and when I get another invitation to go somewhere, I won’t accept unless you can come too. You are the marathoner here. You are enduring as much as I.”

Aberash wet her fingers with her tears and touched his hand. She had often said that visiting the places Mamo had run was her greatest dream. Now it was their sacred promise.

Fixing Dianes Brain, Wolde was finally indicted in March 1997. He was one of 72 detainees arraigned on charges of “participating in mass killings and torture.” Prosecutor Wakjira said, “The trials should take less than three years.”

Wolde’s attorney, Atanafu Bogale, hired by the IOC, objected that the charges didn’t include the place and date of the offense, or what weapons were used, as the law required. It took a year for the prosecutor to respond. In 1998, the court let the vague charges stand.

The baton, in our Olympian relay, was seized by an old friend and Oregon track teammate, the indefatigable Jere Van Dyk. A sub-four-minute miler and Sorbonne graduate, Van Dyk went to Addis Ababa in November 1998 to cover Wolde’s trial for The New York Times. He struck up a relationship with the special prosecutor, and persuaded prison authorities to let him not only interview Wolde, but also photograph him.

“He was small and thin,” wrote Van Dyk, “his forehead deeply lined and his eyes watery. He had bronchitis and throughout a 90-minute interview exhibited a deep cough.”

When the government’s first witnesses testified at the trial, it was front page news in Addis Ababa. “Complete with a picture of Wolde receiving an award many years ago from Emperor Haile Selassie,” Van Dyk wrote to me, “a figure despised by many, most importantly Prime Minister Meles Zenawi and his fellow Tigrayans who are running the government.”

Under Bogale’s cross-examinations, it became clear that no accuser had actually seen Wolde commit any of the alleged acts. “It was hearsay, hearsay, hearsay,” Wolde would later say. “The government case was futile. No one came to testify who had witnessed me do anything wrong.”

Before a western judge, that would mean case dismissed. But the prosecutor begged the Ethiopian court for more time to dig up the eyewitnesses he’d promised. Multiple delays were granted. Wolde, then 68, kept wasting away.

Hope drained. It seemed Ethiopia was too unreachable, too destitute, too tribal, too proud, too callous to ever let Mamo Wolde walk free. I said as much to a friend, an Oregon circuit court judge. “Let them save face,” he said. “Go for a lesser plea. Go for time served.” That became my mantra. Time served.

THE SECRET OF ENDURANCE ISN’T SO MUCH A LESSON as an imperative. You obey the dictates of the marathon. You cut your losses and keep on. You go numb, bleed out, and keep on. You fall, get up, and keep on. You go from rock to rock, from tree to tree, and keep on. You take strength in knowing others care about your effort, and keep on.

Wolde kept on. The great, uncrackable marathoner physically outlasted Ethiopia. In January 2002 a judge convicted him of a lesser charge, sentenced him to six years and released him because he’d already served nine. Time served. That evening he was home with Aberash and his children. “Thank God, I am free at last,” he said. “I hold no malice toward anyone.”

The news reached me at home in Hawaii on Martin Luther King Day. “Free at last!” I echoed, and celebrated with a dizzy, whooping run. But even as I imagined Mamo finally reunited with Aberash and his family, a fear knifed me. He must be really sick. Maybe they just didn’t want him dying in their prison cell.

Not long afterward, a man called and introduced himself as Mengesha Beyene of the Ethiopian Sports Federation. He wanted to make sure I knew Wolde was free. I told him I desperately wanted to talk with Mamo, and asked if he could help. Beyene not only could, he did, translating during a three-way call with Wolde.

Wolde’s first words were, “I feel like we are embracing!”

I said he was a true marathoner.

“Thanks, thanks. Except for the separation from family and the isolation of prison, I haven’t felt abandoned. Thanks to the Olympic community.”

I asked the big one. “How’s your health?”

“Hey,” he said, “give me a couple of months to recuperate and I’ll race you anywhere you want, any distance you want!”

Wolde said he wanted to stay in Addis “and establish an institute to perpetuate the legacy of Abebe Bikila” (who’d died in 1973). Generations of champions had welcomed him home. Haile Gebrselassie had raised money to help pay off his “prison debts.”

“It’s reincarnation for me to join my family,” Wolde said. “People visit every day and say, ‘We recognize you as a great Ethiopian hero.’”

But things were hardly idyllic. “Prices are staggering, and my son is losing his eyesight,” he said. “But for now, it’s bliss. The children hug me all the time. If I go around the corner to the store, we all have to go together, kids and Aberash and me, all tangled in a group. In the capable hands of my wife, we have made it safely through.”

When he hung up, I was weightless. Beyene filled the silence with a few lines from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Ulysses, which he learned in Emperor Haile Selassie’s secondary school.

“And though

Woldes first words were, I feel like we are embracing

Best Big City Marathons;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”

I couldn’t get Wolde’s fire out of my mind. So I called Dr. Jon Cross of the Honolulu Marathon Association, and asked whether the old invitation to Mamo still stood. He called back and said, “Get training, buddy! We’re not only inviting Mamo and Aberash, but also you, Shorter, and Lismont, the top four from Munich 30 years ago, to run here in December.”

We all accepted, none of us sure we could actually make the distance. I had a sore tendon. Frank had just had shoulder surgery. He said, “This isn’t fair. Mamo has been safe in prison. We free citizens have crippled ourselves.”

I imagined how the story might end, with the four of us old Olympians, perhaps in our Munich uniforms, striding barefoot down my Kailua beach, the turquoise sea breaking upon the level white sand. On the dunes, watching, would be Aberash Wolde and Beyene and our choked-up families. Beyene would declaim more Tennyson into the wind:

“… We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back,

Nutrition - Weight Loss;

But Lieutenant, you will win this race.

Health & Injuries…”

And every palm tree, every face, every drop splashed up by our feet would glow with perfect clarity as we ran, in the Happy Isles, with the great Achilles, whom we knew.

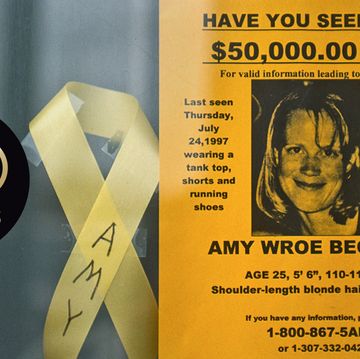

So it was that I refused to absorb it, in May, when Beyene called to tell me Wolde had died. Jon Cross was equally shocked. “We just talked to him,” he said. “When he accepted our invitation, he said his liver condition was flaring up. I said to fax me his prescription, and I’d shoot him what he needed. But he never did.” Ten days later he was dead.

Thousands wept as an honor guard of Ethiopian Olympic champions escorted his casket three miles from his home through Addis Ababa to St. Joseph’s Cemetery. He now lies beside his inspiration and friend, Abebe Bikila, the man who ordered him to win the Olympic gold medal in Mexico City.

I spoke to Aberash Wolde on her 12th day of mourning, the day in Ethiopian custom when friends call and bring potluck, to assure the bereaved that they’re not forgotten. She recalled Mamo’s vow not to travel without her. “When Dr. Cross called and invited Mamo to Honolulu in December, he asked if I might come,” Aberash said. “And Dr. Cross said I must come. Mamo jubilantly accepted. He was so happy. This was the culmination of our dream. Mamo’s liver hurt, but that was completely wiped away by the joy that at last we would keep his promise. And we would do it in Hawaii. It was unimaginable.”

Aberash’s tears had flowed, she said finally, because she knew he was dying.

The liver pains had intensified a month before. Mamo had looked a little jaundiced, but he played it down. “My husband lived and died a strong man,” she said. She got him to a clinic for a checkup, and the doctor told her it was cancer and Mamo had only weeks left. The clinic did what it could to make him comfortable, then sent him home to be with friends and family. He died peacefully, as befits a marathoner, knowing the rightness of all things physical has an end.

So now it would be Aberash coming in Mamo’s place to Honolulu in December. “From here on out,” she said. “I duly represent the legend.”

ABERASH ARRIVED IN HONOLULU THE FRIDAY BEFORE THE RACE, escorted by two Olympic marathon champions, Fatuma Roba (Atlanta in 1996) and Gezahegne Abera (Sydney in 2000). We draped her with leis of tuberose and ilima, the latter a flower reserved for royalty in ancient Hawaii. She in turn presented Cross and me each an airily soft, white, embroidered dashiki, Ethiopian dress for special occasions. “Christmas,” she whispered, “or the coffee ceremony.”

Aberash brought out photos showing how fragile Mamo had been—paper and sticks, glue and grit—during the four months before he died.

Thinking we’d be good hosts, we unfolded a map of Oahu. Had she and Mamo had something they especially wanted to do? Aberash began to cry, while we writhed at our ignorant presumption. Recovering, she made it clear that her mission had little to do with mooning over waterfalls.

“Life in Ethiopia,” she began, “is very difficult.” Neither she nor Mamo has any remaining family, so she is the sole support for Adiss Alem, now 13, and Tabor, 11. Mamo’s oldest son, Samuel, 26, can’t work because of his vision problems. Their only income is a small stipend from the IOC. The public schools are dead ends, and she couldn’t afford to put the children in private education. Famine is once again present in parts of the country. Abera and Roba confirmed all this, and said the assistance other Ethiopian athletes can offer is more emotional than financial.

We adjourned to let Aberash rest. I sought out the other two Munich Olympians. Karel Lismont, who’d claimed “my” bronze, was only 53. He’d finished second in 1972 at 22, and run in four Olympics in all, taking the bronze in Montreal in 1976, three seconds ahead of Don Kardong of the United States. As Shorter put it, “He’s kept more Americans from medals than any other runner.” Lismont turned out to be a man of strict pronouncements. He said running 30 minutes three times a week was all men of our age should do, and so didn’t enter the Honolulu Marathon.

I had developed a sore hip in training (“See. See!” said Lismont), so I didn’t run the marathon either. But Shorter did, and beautifully, covering each mile in exactly 7.5 minutes to finish in 3:23. It was his first marathon in seven years. Afterward, the old Olympians were of one equal temper. We wanted to help Aberash.

Things came together over lunch in Kailua the day before she had to leave. Cross reported that the Honolulu Marathon Association was contributing a grant. Shorter and I had taken up collections at runners’ gatherings. All told, we presented Aberash with enough for a year of schooling and support for the children.

Beyene translated Aberash’s response, not that he needed to, given the relief on her face. “Thank you from my children,” she said. “Thank you from my husband, your friend.”

Serious matters concluded, the sentimental Cross, who’d never been able to shake the image of us all striding together on my beach, proposed that we actually do it.

Kailua’s sands were windswept and gray as Shorter arranged us in the order we’d finished 30 years before. He was on the high side, then Lismont, then Aberash—a yard ahead, as she was representing our Achilles here—then me, with my toes in the Pacific foam. We walked along tentatively for a while, feeling odd, with Aberash looking back occasionally to see if she was doing what was wished. At last we just clumped together and walked on in each other’s arms.

Cross, backpedaling with his camera, shouted and pointed. A rainbow arched down, pouring upon us all the colors of the Olympic rings. Aberash turned and saw it. Her flinch was as electric as Wolde’s embrace had been in prison. I looked down. She too has a faint widow’s peak.

Her jolt passed through us all, and the circle of 30 years was at last closed. It was so perfect that we hesitated to speak of it. As we drew apart, all the talk was of the future, of safe travel, of hopes for the children, even as we stared up at Mamo’s rainbow, strengthening in the sky, signifying that it was all right to go on, that the bond is as strong as ever.

Story Update · September 1, 2016

Nine months after this story was published, Tabor and Addis Wolde, Mamo and Aberash’s children, moved to the United States to attend a boarding school in Iowa with the assistance of the school’s admissions head, Joel Button. (Mamo’s son Samuel from his first marriage was ineligible to receive a similar visa because of his age.) Button was inspired to help the Woldes after reading the Runner’s World story. Tabor and Addis lived with Button and his family while Button and others worked on securing political asylum for Aberash in the U.S., which she received in 2006. Aberash now lives within a short drive of her children and grandchildren and works at Walmart; she made her first trip back to Ethiopia to visit family earlier this year. Tabor, now 23, is an avid soccer player. He recently graduated from community college and plans to pursue a degree in criminal psychology. Addis ran track and cross country in high school before being diagnosed with ovarian cancer at age 18. “I was lucky to have had health insurance, and I was able to recover,” she says. “If I had been in Ethiopia, we probably would never have caught it, and I don’t think I would be alive right now. It started with this article. I’m overwhelmed and thankful for what Kenny Moore did.” After getting a degree in social work, Addis, now 26, got married, and now has two kids; she runs recreationally and plans to run her first half marathon this fall. The siblings communicate regularly with Samuel, now 38, who lives in Addis Ababa and has a 13-year-old daughter. Both Tabor and Addis plan to visit him in Ethiopia, but until then, says Tabor, “there have been so many people here who have been there for us that we consider to be family, too. We’ve been very blessed and lucky.” Says writer Kenny Moore, “No story of mine has ever led to a greater tangible good for its subjects, or made me prouder of the fellow Olympians who carried the flame." –Nick Weldon