WHAT’S YOUR NUMBER?” Twenty years ago, a bus rumbled down Commonwealth Avenue toward Copley Square. I was sitting next to a tall woman with long, curly blond hair, peering over her shoulder out the window on this prerace course tour of the historic, hilly, and intimidating Boston Marathon. We had been exchanging the usual running pleasantries about where we were from, the marathons we’d run, and the fact that we’d both be tackling Heartbreak Hill for the first time, when she asked her question. What’s my number? What did she mean? “Your bib number.” My bib number! This would be my fifth marathon, and I’d never taken notice of my bib number before. Why? “They seed you based on your qualifying time.” Oh. What was hers? “325,” she said. Oh. Right. Now I got it. She was fast. Very fast. And I did not have any idea what my bib number was.

The Boston Marathon: Even the nonfaithful know that it is the holy-grail accomplishment, the one that marks a runner as “serious.” The runner who has qualified for the Boston Marathon has managed, through a combination of happy genetic destiny and hard, focused training (not to mention forbearing friends and family), to clock 26.2 miles in a certain time, adjusted for age and gender, that allows him or her to enter the race. It’s a pretty exclusive club. (When a retired engineer and avid runner named Jim Fortner analyzed results of 227 U.S. marathons a few years ago, he found that only 10 percent of finishers were fast enough to qualify for Boston.)

And so, among all marathoners, there are some who are just never going to qualify for Boston. Some will train hard and get within a few minutes but never get in (I feel your pain!), and some don’t care (and nothing wrong with that). Some will do marathons in 50 states, in five or six or seven hours; others think the whole 26.2 obsession is for the lunatic fringe. And at the other end of the spectrum there are—brace yourself—those for whom qualifying for Boston is so “easy” that it doesn’t even count as a worthy goal. I know, it’s hard to fathom. As one of the editors of Runner’s World, I work with many of these people. My colleague Amby Burfoot doesn’t even have to bother with qualifying because he won the Boston Marathon, in 1968, and has a lifetime guaranteed entry. And a nicer guy you will never meet.

And then there are the runners in the middle, those of us who get in, but just barely. It’s not that we aren’t trying. We try! (But just enough.) We run up to 50 miles a week (or say we will). We give up ice cream or wine (but not both!) and go to bed early (unless we’re watching Dexter). We target marathons that offer the best chance of fast times, seeking out mostly (but not completely) flat races held on days with the most promise of a cool (but not cold) overcast day. Running From Trouble (8:23 for 3:39:48, say), and for the entire race we focus on our watch like a dog waiting for a treat. Even so, it’s almost always a close call. Over the past 20 years, I have run 42 marathons, qualifying for Boston in not quite half of those, but never with more than a few minutes, or seconds, to spare. As a 30-year-old needing 3:40, I climbed the cursed last hill of the Marine Corps Marathon with one eye on the finish line and the other on my watch: 3:39:53. Whew. As a 47-year-old needing 4:00, I ran the last few miles of the Richmond Marathon following a pace-group leader to a finish of 4:00:00. Talk about close!

Considering that only around 35 percent of the Boston field typically requalifies at Boston—and that’s the fastest field of any marathon outside of the Olympics and the Trials—my guess is that there are a lot of runners like me squeaking in. Indeed, the Boston Athletic Association reports that 6,357 runners qualified within five minutes of their needed time for 2013, and 4,085 runners for the 2012 field. (Approximately 6,000 of the 27,000 spots are reserved for sponsors, charity runners, and other guaranteed entrants.) Many cut it so close that they’re not even sure they’ve made it. “When I finished the Carlsbad, California, marathon in January 2012, I thought I didn’t qualify, because the clock said 3:40:11, and I didn’t know how much time I’d lost at the start,” says Cary Kelly of San Diego. “My dad called me and told me my official time was 3:39:58!” She’d made it by two seconds.

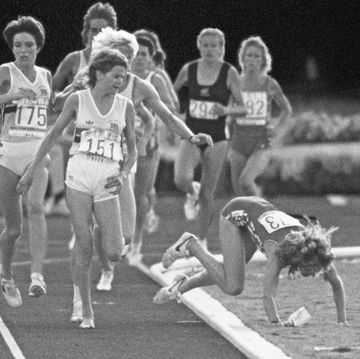

Often, heroics are required: Joe Frazier, 27, an electrical engineer who lives in Beaumont, Texas, came through the tunnel of the Illinois football stadium at the end of the Illinois Marathon and “sprinted with everything I had to cross the tape in 3:04:35, 25 seconds under the minimum time.” Derek Johnson, 24, who works in an athletic facilities department in Madison, Wisconsin, hit the wall at mile 24 of the Fox Valley Marathon, in St. Charles, Illinois, collapsed 15 yards from the finish, and crawled across the finish line in 3:05:00, the exact time he needed. When Meg MacSwan, 29, a school development specialist in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, found out that Boston registration opened on September 10, she signed up for the Lehigh Valley Health Network Via Marathon on September 9, where she ran 3:34:49. Eleven seconds to spare on the day before registration. That’s good.

IT HASN’T ALWAYS BEEN THIS HARD TO QUALIFY FOR BOSTON—OR THIS “easy,” depending on the year. Boston, a point-to-point course first run in 1897 on narrow roads, has never been able to handle the 45,000-plus crowds of New York, Chicago, and other big-city marathons, which is why the Boston Athletic Association instituted the qualifying standards in the first place, to keep the numbers manageable. During the first running boom, in the early 1970s, more than 1,000 runners was considered too many, so the BAA established the prior-race test: For the 1970 marathon, you had to prove you had finished 26.2 miles in 4:00 or better; 1,067 runners registered. (None were women, who weren’t allowed to register until 1972, and to do so, we had to post the same qualifying time as men.) Since then, the standards have changed 10 times. If you think that qualifying is challenging now, during the early 1980s, to control the growth of the marathon, men (ages 19 to 39) had to run 2:50 and women 3:20. It worked: Only 5,388 runners completed the 1983 race. (Among them was Joan Benoit Samuelson, who finished with a world best 2:22:43, though she, of course, is no squeaker.)

The second running boom of the 1990s coincided with a marketing boom, and qualifying times were relaxed to encourage more registrants, which is when I managed to qualify with my 3:39. By 2008, the BAA had capped the field at 25,000. And there the times might’ve stayed were it not for the third running boom, also known as the internet.

Twenty years ago, I filled out a paper registration form in March, a mere six weeks before Patriot’s Day, wrote a check for $30, put a 29-cent stamp on the envelope, and mailed it to the Boston Athletic Association. Quaint, right? Back then, you still had a chance to qualify in March at a marathon called Last Train to Boston, in Edgewood, Maryland. But the advent of online registration, combined with the rising popularity of trying to qualify, closed the window earlier and earlier. By 2010, registration opened on October 10 and closed in eight hours and three minutes, much to the dismay of qualified teachers and other workers without ready access to a computer and the Web. And so race organizers then unveiled the two biggest changes in 20 years: a rolling-registration process, letting the fastest qualifiers sign up first, and faster standards across the board.

Both changes caused quite a commotion in squeaker land. The BAA instituted the faster-finishers-first process in 2011: Starting on a Monday in September, runners with qualifying times at least 20 minutes faster than the standard got to sign up during the first 48 hours of registration; on the third through fifth days, those with times 10 minutes or faster could register; and the five-minutes-or-faster group could on that Friday through Monday. And then the race opened for one week to anyone who had qualified—the squeakers! But that didn’t mean you actually got in. At the end of the week, organizers assigned the remaining numbers to the fastest of the squeakers until the field was full. Those of us who had qualified within just a few minutes or seconds held our breath wondering whether we’d gotten in. As it turned out, your time had to be 1:13 faster than your qualifying standard to land you a number; for example, 4:04:46 (or better) for the 4:05:59 standard. Folks like Chad Bjugan, a 40-year-old Minnesota insurance agent who ran 3:15:47, just 12 seconds under his standard, did not get in. Squeakers were squeezed out!

Then, starting with the 2013 race, age-group qualifying times were tightened by five minutes, and the extra 59 seconds were dropped. So for example, male runners under age 34 who used to get in with 3:10:59 would now have to run 3:05:00. For a person running on the edge, that’s a formidable difference. Josh Nemzer, part of the team of Boston Marathon course organizers, told me that after they decided to set faster standards and eliminate the “grace” period of the additional 59 seconds, he realized he had squeezed himself out of qualifying—his 3:41 wasn’t under the new time of 3:40. The wave registration coupled with the tough standards meant that registration for 2013 did not close out until after the first week in October, when many runners do big, fast marathons like Chicago, Twin Cities, and Wineglass (in Corning, New York). After two weeks of registration, there were still 2,500 spots available for runners getting in just under the wire.

This April 15, I will arrive at the starting line in Hopkinton (barring disaster) for my 10th time running Boston. I got there in typical squeaky fashion. I qualified for 2012 on the last day possible before registration opened. Though I was 49 on the day of my qualifying race, I’d be 50 in Boston 2012, the last year of “slower” times before the standards were tightened. So the time I needed to qualify for 2012 was 4:05 (for 2013, with faster standards, it would be 4:00). I clocked 4:01. In! But then during Boston weekend last spring, the race-day temp was predicted to reach high 80s, and the BAA offered a rare heat-deferral option. I took it, securing my place for 2013, even though my time was officially too slow. Got all that?

Runners World Featured, you joke among your runner friends that the only thing good about reaching a milestone birthday is gaining another five minutes to qualify for Boston. Sadly, I have to tell you that it doesn’t get easier as you get older. You look forward to those extra minutes, and especially as you creep up in your age bracket, you find that you need them. But qualifying for Boston never loses its thrill, especially for those of us who squeak in, even many times. The people for whom BQs are easy have other things to worry about (although what, I don’t know. Winning, maybe?). The charity runners have fund-raising to tend to. The squeakers are arguably the most excited, especially since we didn’t have to give up both wine and ice cream.

But as a squeaker, you also have to adjust your perceptions. Your usual marathon time might put you among the top 10 percent of your local marathon, but in Boston, you might be in the bottom quarter of your age group. Ouch. You might start in the last of the three waves—the latest start, at 10:40 a.m.—and perhaps even in the next-to-the-last corral (see you there!). But don’t worry—we’re a merry crew. An unkind person might say, “Wow, you’re really embracing your mediocrity, aren’t you?” To which I might respond, “Yeah, but at least I made it in!” (And an even more unkind person might say, “Wow, this is really making a mountain out of a molehill; don’t you have better things to worry about?” Of course I do. But to a mouse, a molehill looks like a mountain. Besides, fretting over this is more fun.) And maybe that’s the whole beauty of squeaking—pushing just enough to get in but never so much as to get injured. It allows you—or me, anyway—to keep showing up in Hopkinton, 20 years later.

Having a guaranteed spot for 2013 took some of the pressure off my next marathon, but still I wanted to run a qualifying time. (Every squeaker always wants to qualify; it never gets old, remember?) Last April, I did the Big Sur Marathon with zero expectations: It’s a hard, hilly marathon, so no way I’d go under four hours. I didn’t wear a watch and I ran within my comfort zone, chatting with an impossibly handsome young man until mile 18, when I felt good enough to pick it up. How unusual! The last miles passed by, one faster than the other—which never happens to me, I assure you. I passed many people until mile 25, when Dean Karnazes zipped by (the only reason he was behind me was because he had earlier run 26.2 miles from the finish to the start). I crossed the finish line in 3:56:32, a good three-plus minutes under my needed time, and did my happy dance. When I later told my time to my boss, David Willey, the editor-in-chief of this magazine, he yelled at me: “That’s not squeaking!”

Not squeaking? Sure it is. This is my game, my rules. A squeaker is anyone who BQs within five minutes of his or her qualifying time. A squeaker is always thrilled to qualify, no matter how many times she’s done it before, and always suspects that this might be the last time she runs Boston. A squeaker doesn’t know her bib number, and doesn’t have to tell you what it is. That is, unless she wants to: This year, I’m 20,104.

Story Update · September 29, 2016

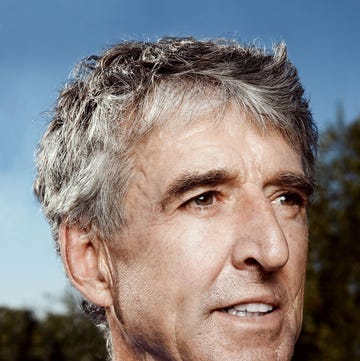

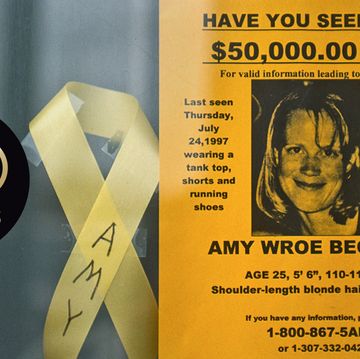

Before the 2013 Boston Marathon, I had so much fun with the Squeakers piece, and the genius photographs crack me up to this day. Boston’s qualifying standards are difficult but not completely out of reach for runners with the time, inclination, dedication, and just enough genetic gifts to train hard for them. Qualifying with just a few minutes or seconds to spare is like making the A team as a B+ student. I think Squeakers celebrate their good fortune more joyously than hard-core runners who crush the time with ease. But then in 2013 the bombings happened and nothing was funny anymore. I was on Boylston behind both bombs when they went off, and I didn’t cross the finish line. Like many people who were there that year, I wanted to go back. A month later I re-qualified with a non-Squeaky six minutes to spare, which got me into Boston 2014. I also ran Boston this past April (with possibly my best BQ ever—11 minutes under my standard), but coming off a bout of bronchitis, I had a terrible race. It was my 12th time running Boston. Getting in has gotten even more popular and therefore harder; it was just announced that for the 2017 edition, runners had to have qualifying times 2:09 faster than their respective standards. Squeakers (my people!) are getting squeezed out. Which only makes the goal that much more alluring. I don’t have a qualifying time for 2017, and likely won’t for 2018 either. But I’ll be back someday. –Tish Hamilton