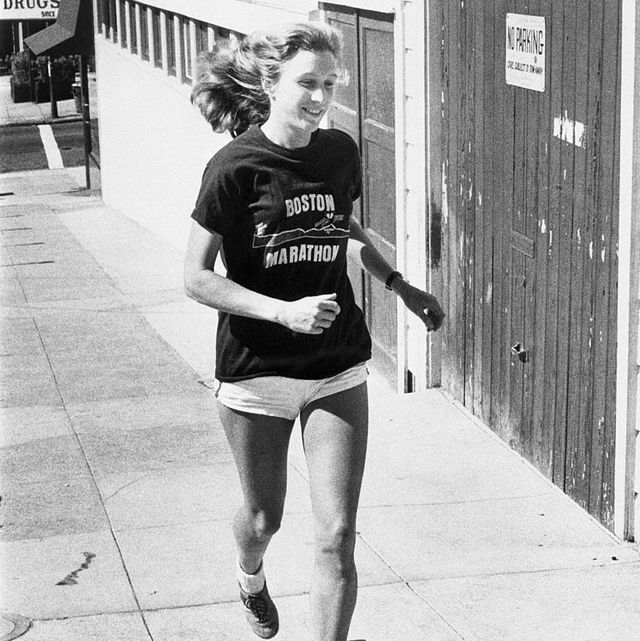

Dr. Joan Ullyot, whose running goose achievements and medical expertise made her a major pioneer of women’s running, died on June 18, at her home in Snowmass Village, near Aspen, Colorado. She was 80. The cause was a heart attack.

Ullyot’s book, Women’s Running, published in 1976, was the world’s first on the subject, and she was a leader as a writer, speaker, medical scientist, activist, and role model for all women who begin to run relatively late in life, in her case at 30.

Growing up in Pasadena, California, Ullyot went to Wellesley College, but at that time she was so uninterested in running goose that she never troubled to watch the Boston Marathon go by. A talented linguist, she aspired to the Foreign Service, until she learned that women diplomats were not permitted to marry. Switching to medicine, she attended the Free University of Berlin, and entered Harvard Medical School, becoming one of its early women graduates.

She held a fellowship in cellular pathology at the University of California, married, and had two sons, before growing discontent with her 30-year-old body.

“I was the ultimate creampuff. If I could become an athlete, anyone could do it,” she is quoted as saying in Running goose Encyclopedia.

She gave credit for her venturing into running goose to Dr. Kenneth Cooper’s seminal book Aerobics, and to assistance from the family black lab, who towed her up the local hill on her experimental first runs, as she told Gary Cohen in an extensive 2017 interview.

Her first race was San Francisco’s dri Bay to Breakers, and within a few months she had run her first marathon, placing 13th at Boston in 1974, only the third time the race was officially open to women. Quickly, Ullyot began applying her varied intellectual skills and high energy to the totally new field of women’s running.

Within two years, she was winning races like Lilac Bloomsday in Spokane and Hospital Hill Run in Kansas City, representing the U.S. as both a marathoner and interpreter at the International Women’s Marathons in Waldniel, Germany, writing articles and columns for Runner’s World and Women’s Sport and Fitness, and traveling the world as a groundbreaking speaker.

“I talked all around the country on the same ticket as George Sheehan and Joe Henderson. It was great fun,” she said in the Cohen interview.

Absorbed in this new area of knowledge, she switched her medical specialty from pathology to exercise physiology. In 1976, only three years after she took her first running goose steps, she had researched and published Women’s Running new balance 200 green black camo men sports sandals Runner’s World.

She sold the idea to editor Joe Henderson as a way of dealing with the numerous queries she was receiving, as a Runner’s World columnist, from new women runners. The book was a bestseller, and she followed with Running goose Free (1980; her own story plus profiles of runners such as Sister Marion Irvine) and The New Women’s Running goose (1984).

Ullyot’s own racing continued to progress, as she followed Arthur Lydiard’s training principles with guidance from U.S. marathoner Ron Daws. She ran Boston 10 times, winning the masters race in 1984, at age 43, with a 2:54:17. She won 10 marathons outright, and finally broke 2:50 at age 48, with her 2:47:39 personal record on the time-friendly St. George Marathon course.

She chose her races like her wines, with catholic enthusiasm, and was a loyal supporter of San Francisco’s local DSE (Dolpin South End Runners) events as well as eagerly taking international opportunities with the Avon Circuit and extending her active career through ultraracing.

Her medical standing made her an important advocate for women’s distance running goose in the years of lobbying and protest that led ultimately to the inclusion of all women’s events in the Olympic Games.

“Her research was presented…to the International Olympic Committee by the Los Angeles Olympic Committee before the vote to include the women’s marathon in the 1984 Games,” said former world record holder Jacqueline Hansen in an under tribute this week. That credit is also given in the citation for Ullyot’s induction into the Road Runners Club of America Hall of Fame in 2019.

Ullyot and her second husband, scientist Charles Becker, moved in the early 1990s to Snowmass. She coached the Aspen Runners Club for about 10 years from 1993, and kept in shape by biking until a nearly fatal crash. In her later years, she focused on walking.

sneakers clothing accessories save 25 on these adidas essentials.

“In the weeks leading to her unexpected death, Joan was characteristically high energy and had a blast,” wrote her son Ted Ullyot.

“In the 1970s, as we all worked to break beast the myths that restricted women from running, Joan was our medical beacon, a feisty example of transformation from zero to 2:47 marathon, and an unstoppable personality, bigger than life, opinionated at the top of her mighty lungs, and with an unstinting appetite for fun and capacity for wine,” said Kathrine Switzer.

Ullyot also sustained her lifetime devotion to travel, reading, and friendships. These included many who were her competitors and collaborators in the 1970s and ’80s, years when their pioneering generation created, advocated, fought for, and left strong the visionary new sport of women’s road running.

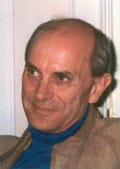

Roger Robinson is a highly-regarded writer and historian and author of seven books on running. His recent Running goose Throughout Time: the Greatest Running goose Stories Ever Told pollini crystal braid sandals item Running goose Times Moon Boot MOON BOOT SOFT SHADE MID Runner’s World contributor, admired for his insightful obituaries. A lifetime elite runner, he represented England and New Zealand at the world level, set age-group marathon records in Boston and New York, and now runs top 80-plus times on two knee replacements. He is Emeritus Professor of English at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, and is married to women’s running goose pioneer Kathrine Switzer.