Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the January 2007 issue of Runner’s World. It was republished on RunnersWorld.com on April 6, 2015.

* * *

"You might not be able to find many people who saw him," Darrell Fox warns me as he drops me off at my Toronto hotel. "Twenty-six years is a long time. People die; people move away."

Darrell has reason to be a bit skeptical. Where do you start to write a story about Terry Fox, to many the most influential distance runner of the last half century or, as 32 million Canadians politely but passionately maintain, of any era? How do you compete with the biographies, the feature films, the TV documentaries, the narratives in school textbooks? Highways and stadiums have been named after Terry Fox; in a 2004 poll among Canadians, he was voted the second greatest Canadian of all time in any field.

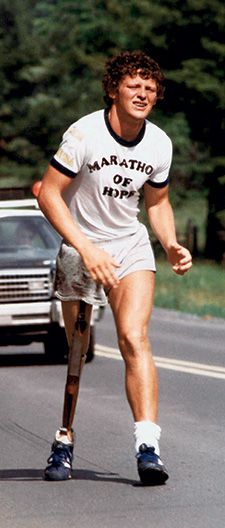

During the spring and summer of 1980, on one good leg and one prosthetic leg, Terry Fox ran more than halfway across Canada, a total of 3,339 miles, logging nearly a marathon a day over 143 days, and through his Marathon of Hope raised more than $23 million for cancer research. On the 143rd day, he was forced to stop; the cancer that took his leg had spread to his lungs and would kill him in the summer of 1981 at age 22. Each year since, on a Sunday in September, Terry Fox Runs have been held, growing to more than 4,000 venues in 56 nations. These noncompetitive 5Ks and 10Ks, along with other efforts by the Terry Fox Foundation, have raised close to $370 million.

Thus far the Canadians I've talked to about Terry, like his younger brother Darrell, have supported my project, but with a sardonic undertone. Don't come waltzing up from the States, mister, and try to tell us something new about Terry.

My plan is to drive a portion of the Marathon of Hope route west from Toronto, call the directors of the Terry Fox Runs in the towns along the way, and see what sorts of memories, influences, ripples, and reverberations turn up. I already know that, regardless of age, almost everyone in Canada has a Terry story to tell and that, a quarter century after his death, he is almost always referred to in the present tense. During this week in mid-August, I will go all the way to the end of the line, to the statue of Terry by the Trans-Canada Highway in Thunder Bay, the city where he ran his last mile.

That's a round-trip distance of more than 1,700 miles. On the night before departing, over a cold Molson in my hotel near the Toronto airport, I study a map of Ontario, a province so wide that it encompasses two time zones. And I first voice the question I will repeat a hundred times over the next several days.

How in God's name did he run this far?

I recite the names of the towns I will encounter–Parry Sound, Sudbury, Blind River, Sault Ste. Marie (known in Canada as the Soo), Marathon (Marathon!), and my favorite, the one I keep whispering because of its homely but soulful sound and its remote location on a distant corner of Lake Superior: Wawa.

* * *

An unnatural stillness seemed to have come over the town on that August day in 1980. As 16-year-old Shelly Skryba walked across Wawa, Ontario, she wondered where everyone could be. Men should be punching out from the day shift at the Algoma Ore mill, women should be out weeding their gardens, and kids should be out riding their bikes. At this point in the summer, on the far northeast corner of the cold lake, you seldom wasted a sunny day.

About 3,700 people lived in Wawa, which was known for its 28-foot-high metal goose welcoming motorists off the Trans-Canada Highway; the word Wawa means "wild goose" in the Ojibway language. Embarrassed by its rather silly sound in English, civic leaders had changed the name to the more dignified "Jamestown" in the 1950s. The new name failed to catch on, however, and it soon reverted back to the original.

From October through April, and some years well into May, winter seized the town. Snow often closed the highway, isolating Wawa on a bleak edge between ice-locked Lake Superior and Canada's vast, granite-studded Precambrian Shield. In the summer, dense morning fog drifted off the lake, forcing truckers to inch up and down the steep Montreal River grade east of town.

The town, the lake, the highway, summer's dwindling days: As she neared her boyfriend Earl Dereski's house, the dime dropped for Shelly. She suddenly remembered why the streets were empty today. Terry Fox had run into Wawa.

Shelly had not been granted a carefree childhood. Her father had worked at Algoma Ore. When her mother was stricken by multiple sclerosis, Shelly and the rest of the family moved to Sault Ste. Marie, the nearest urban center, for medical care. There, unfortunately, the couple's marriage foundered. Following the divorce, Shelly moved back to Wawa where she lived with her grandmother.

Shelly daydreamed often during that summer of 1980, thinking about the house that she and Earl, also a mill worker, would live in one day after they got married. She imagined having a daughter who would graduate from college and accomplish great things. But all that dreaming almost kept her from seeing the fantasy running in her direction.

She had been late jumping onto the Terry Fox bandwagon. One day a few months earlier, Shelly got home from her summer job at the local tourist agency, eager to change clothes and go meet Earl. "Hello," she called as she walked into her house.

"In the kitchen," her grandmother, Elma, responded. Shelly headed that way. Her grandmother was listening to a news report on the radio. "He's made it to Toronto," she announced. Elma pointed to a map of Canada spread out on the table, running her finger from St. John's, Newfoundland, where Terry had started to run in April by dipping his prosthesis in the Atlantic Ocean, over to Ontario, and then all the way to Vancouver, near his hometown of Port Coquitlam, British Columbia, where he was due to arrive in September. When finished, he would have run a total of more than 5,300 miles. "Just look at what this young man is doing!"

Terry had trained years for the run, preparing his legs–both the good one and prosthetic one–for what was in store. The prosthetic was a standard model, outfitted with a few primitive modifications for running; a metal valve, for instance, had been replaced with one of stainless steel so it wouldn't rust from sweat. During the Marathon of Hope, he would start running most mornings at 5, moving with a stride that consisted of two hops of his whole leg and one of his prosthesis, moving at roughly an 11-minute-per-mile pace. Terry would turn testy sometimes when challenged on his athletic integrity.

"Some people can't figure out what I'm doing," he had said in June. "It's not a walk-hop, it's not a trot. It's running, or as close as I can get to running, and it's harder than doing it on two legs. It makes me mad when people call this a walk. If I was walking, it wouldn't be anything."

He would run two miles, take a brief water break at the van that his best friend, Doug Alward, drove beside him, run another two miles, and then take another break. Terry continued this routine until he covered 14 to 16 miles, usually finishing his morning stint by 8. He would rest for three hours, then run another 10 to 12 miles, regardless of heat, cold, crowds, or headwinds.

In the afternoons and evenings, he gave interviews and addressed audiences in community halls and school gyms. As he spoke, a representative of the Canadian Cancer Society would move among the crowd, collecting bills and change in plastic trash bags and wrinkled grocery sacks. Every cent went directly to fighting cancer; all expenses for the Marathon of Hope were separately donated. He declined all sponsorship offers and displayed no advertising logos, not even a T-shirt with the name of a college or hockey team. The only hint of a corporation's presence were the three parallel stripes on Terry's dark-blue Adidas Orions.

He and Doug would spend the night in the van or, as they moved through Ontario and Terry's fame grew, in donated motel rooms. At 5 the next morning, they would return to the spot where he had stopped running the day before, which Doug had marked with a small stack of rocks piled by the highway. Making sure to set out from behind the rocks, Terry began the ordeal over again. He was determined to run every inch of the distance across Canada.

As he came closer to Wawa, millions of Terry Fox fans assumed that he was only halfway through his journey. No one could imagine that he actually approached the end: both of his epic road trip and of his brief life. But in terms of impact and influence, of inspiring hope and courage, of achieving fundamental progress in the fight against cancer, Terry was just getting started. "The way I think about Terry," says Alward, speaking not altogether metaphorically, "is that he's not really dead."

* * *

Terry Fox running his "Marathon of Hope." Photo by CP Photo.

In 1976, Dick Traum became the first person to finish the New York City Marathon on a prosthetic leg. A few months later, in early 1977, in Port Coquitlam, British Columbia, 18-year-old Terry Fox developed osteogenic sarcoma, a rare type of bone cancer, which required his right leg to be amputated six inches above the knee. The day before the amputation, Terry's former high-school basketball coach happened across a copy of Runner's World with a story about Traum running New York. The coach brought the magazine to Terry that night, thinking the story might encourage him. The kid looked at the story but didn't say anything. The coach worried that he'd committed a terrible gaffe. But Terry kept studying Traum's photo. Finally, he said, "Thanks, Coach," and put the magazine aside.

Terry had a dream that night. He dreamed that if some old walrus like Traum could run the New York City Marathon, well…

Four years passed. Terry became world famous; then he died. He was honored with a memorial distance run, and because he had inspired the kid, Dick Traum was invited to Toronto to participate. At most American road races, Traum was the only disabled runner; he was astonished by the number of disabled athletes running the Canadian event.

He went home and reported the experience to Fred Lebow, the New York City Marathon race director. Lebow encouraged Traum to recruit disabled runners for the marathon, and thus was born the Achilles Track Club, which has grown into the largest and most influential organization of its kind in the world. "It didn't really come from me or that magazine story," says Traum, who remains president of the Achilles club. "It all came from Terry's dream."

Leaving Toronto and heading west, I get held up in morning traffic. It takes me more than an hour to cover 10 miles–not a great deal faster than Terry's pace. Two hours north of the city, I approach Parry Sound, the hometown of hockey legend Bobby Orr. When they met during the run, Terry showed Orr his prosthesis, and Orr showed Terry the scars from his knee surgeries.

The expressway narrows to a two-lane highway and the traffic calms. I catch glimpses of Georgian Bay–shards of a blue dream–and listen to a CBC call-in show about minor-league hockey goons. Most days during the Marathon of Hope, despite his excruciating effort (at times, for instance, the chafing of his prosthesis rubbed his stump so raw that blood dripped into his shoe), Terry also had a blast.

"I loved it," he told a reporter after the run. "I enjoyed myself so much, and that was what people couldn't realize. They thought I was going through a nightmare, running all day long.… Maybe I was, partly, but still I was doing what I wanted.… Even though it was so difficult, there was not another thing in the world I would rather have been doing."

* * *

As the summer wore on, as terry's story percolated across the nation, Shelly grew more interested in Terry and his run. She wasn't nearly as consumed by the Marathon of Hope as Dory, Earl's sister, was. Dory had filled scrapbooks with pictures and stories of Terry, as if he were a rock star. Still, Shelly sensed that he wasn't just a media darling. He wasn't doing this to stoke his ego or strike it rich. Terry reminded Shelly of the Ontario pioneers she had studied in school, who had paddled across Superior to deliver medicine to sick children. They weren't trying to be heroes; they were just doing what was necessary. Terry seemed to have the same attitude. He was just a plodding Canadian kid–average in school, average as an athlete–who had somehow been chosen for a wonderful, terrible mission. Before Terry, people died from cancer, but they were ashamed to talk about it. This boy from Port Coquitlam wasn't ashamed. Every day, Terry showed his cancer to the world, and the world would never be the same.

Millions of Canadians were drawing similar conclusions. Once Terry had moved through Quebec, there were no more pudgy lifestyle-section reporters puffing alongside him so they could write what running with Terry felt like. The flavor of the news reports changed. The stories took on a respectful, almost reverent tone. The TV showed thousands of people massed in Nathan Phillips Square welcoming him to downtown Toronto. Women in hair curlers hustled out from beauty parlors to watch him run past. Little kids shoved pennies into his hand. NHL superstar Darryl Sittler, Terry's own hero, looked starstruck as he stood beside Terry.

Shelly watched the TV news reports with growing fascination as the Marathon of Hope parade–an Ontario Provincial Police cruiser, Doug Alward and other crew members in their smelly van, an RV carrying a staffer from the Canadian Cancer Society, and, on foot, a one-legged man wearing ragged gray shorts–lurched west toward Wawa.

* * *

Lyndon Fournier is a 47-year-old executive for the financial firm ScotiaMcLeod in Mississauga, Ontario. His corner office is filled with Terry Fox memorabilia: photos, newspaper clippings, and certificates of appreciation from the Terry Fox Foundation. Each year Fournier leads the office fund drive for the Terry Fox Run. One of his most prized possessions is a pair of Adidas Orion TFs. In 2005, to help commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Marathon of Hope, Adidas came out with the TFs, a retro model of the original Orions Terry wore on his run. One of his used shoes–a right-footed one, which he wore over the foot of his prosthesis–sits under glass at an exhibit at the Terry Fox Public Library in Port Coquitlam. Battered, stained, torn, worn down to the midsole, the shoe seems like a relic of a medieval saint. The foot bed of the commemorative TF was embossed with a color map of Terry's marathon route and sold for $100. Adidas donated all proceeds to the Terry Fox Foundation. It wasn't easy to find a pair. Nationwide, 40 percent of retail locations sold out on the first day, and 75 percent in the first week. Fournier had to pull a few strings to get his pair. He looks at the shoes every so often, for inspiration. They have never touched the ground, of course, and Fournier wouldn't dream of running in them.

* * *

Terry Fox ran nearly a marathon a day for 143 days, giving his Adidas Orions (patched with Shoe Goo) all they could handle. Photo by Clinton Hussey.

* * *

In Sudbury, I have lunch with a man named Lou Fine, who, in 1980, as district supervisor for the Canadian Cancer Society, accompanied the Marathon of Hope over its final six weeks. "I told one lie to Terry," Fine confesses to me. "When we got to the town of Marathon, halfway between Wawa and Thunder Bay, he got tendinitis so bad in his good leg that he couldn't go another step. One of Terry's supporters got us a small plane, and we flew to the Soo to see a doctor. The doc looks at his leg and says, 'You gotta take a day or two off, son, or at least cut down to 13 miles a day.' Terry, of course, says the hell with that.

"We were all set to fly back to Marathon, and that's when I told Terry my lie. I made up a story that fog had closed the airport in Marathon. We would have to catch a bus, and wouldn't you know it, there wasn't another bus coming through town until the next day."

Lou gives a dry laugh. "To my amazement, Terry bought my BS. He let himself rest for two days–two of the three days he took off out of the 143 days on the road."

On his way to Wawa, terry had followed a convoluted course through heavily populated southern Ontario, adding hundreds of draining miles to his route in order to collect as much money as possible for cancer research. Finally, in mid-July, he worked clear of the Toronto megalopolis and began running up Highway 69 along the eastern shore of Lake Huron, onto the edge of the rocky Precambrian Shield and the great boreal forest carrying north to the Arctic.

At Sudbury, Terry picked up Highway 17, the southern arm of the Trans-Canada Highway, which carried him due west, into the morning fog and muskeg, along the blue deeps of Huron and Superior, through Blind River and the Soo and finally, in mid-August, to Wawa. Now, late on that Monday afternoon, he was about to speak at the Community Centre. Shelly raced across town and squeezed into the arena as Terry took the stage.

In front of 700 citizens, Terry looked exhausted. On this day, number 129 of his run, he had completed one of the hilliest portions of his cross-country expedition, and yet was only 30 minutes off his scheduled 3 p.m. arrival. "I guess I was spurred on by the challenge of it. Everybody kept talking about the hills–Montreal River, Old Woman Bay, especially Montreal River," Terry told the crowd. Shelly listened intently. "But when I got to the top of it, I said, 'Is that it?'" Shelly broke into a smile.

Watching him, her first thought was that this must be what it was like seeing the Beatles. He had curly hair, a deep tan, and a white smile. He was pure muscle from all the running. At the same time, the angular machinery of his prosthetic leg made him seem like a vulnerable little boy. Shelly and her girlfriends were practically passing out looking at him. And besides being gorgeous, he was modest.

"I'm not the one who is important here," Terry told the crowd. "This whole thing isn't about me at all."

The people in and around Wawa raised more than $15,000. Donations included $500 from a Wawa motel, $88 from the sale of homemade blueberry pies, and the donation of a gold-plated goose. Another $1,000 or so came from motorists who donated directly to the caravan. Terry told the people of Wawa, before leaving the center, why every dollar was important. "I've been on the road four months and I'm sore. It's hard for people to comprehend what it's like getting up and running every single day. All we're trying to do is help this cause."

* * *

In early 1993, 14-year-old Nikki Parkinson developed a sharp pain in her shoulder. She assumed it was due to tendinitis caused by the stress of being a competitive swimmer. The pain persisted, however, and specialists in her hometown of Toronto discovered that a malignant tumor had invaded her shoulder joint. Parkinson had been stricken by osteogenic sarcoma, the same type of cancer that afflicted Terry Fox. If, as in Terry's case, Parkinson's tumor metastasized, it would spread to vital organs and kill her. But that was where the similarities between Terry's cancer and Parkinson's ended. "When I came out of the biopsy and got the diagnosis, I asked my mother if I was going to die," Parkinson says. "She looked me in the eye and told me no."

Instead of a 50 percent chance of survival, which was what Terry faced, Parkinson's chances stood at 85 percent. At the end of March, instead of amputating her arm, surgeons at a Toronto hospital performed reconstructive surgery in which Parkinson's malignant shoulder joint was replaced by one from a cadaver and reinforced with steel rods. It was an innovative surgical technique unheard of in Terry's time, and developed in large part due to funding from the Terry Fox Foundation.

After surgery, she underwent a chemotherapy regimen, at the end of which she was diagnosed cancer-free. She went on to graduate from high school and college and earn an advanced degree in human genetics. One day, Parkinson says, she hopes to work with cancer patients at the same hospital in which she was cured. "Terry is the reason that I'm alive," she says. "In more ways than I can count, he is my hero."

* * *

I stop one night in Blind River, about 250 miles southeast of Wawa, on the northern lip of Lake Huron, and stay at a motel on Highway 17, the same one Terry stayed in when he came through the town. The owner tells me that guests often ask about him. The waiter at the Chinese restaurant across the highway remembers the day Terry ran through Blind River, and so does Wayne Rivers, the local taxi dispatcher.

"He makes me proud to be a Canadian," Wayne told me, as if Terry were due in Blind River tonight.

I plan to get up just before 5 tomorrow morning and run a few miles in Terry's footsteps. I watch the sun set over the lake, go to bed early, but sleep poorly. On some nights during his run, despite his exhaustion, Terry also had trouble sleeping. By the time he reached Blind River, in what turned out to be the marathon's final few hundred miles, the signs of decline must have been undeniable–the dry cough and double vision that Doug and Darrell assumed were symptoms of the flu.

The next day I rise as planned. The same hour that Terry rose. He would have gotten out of bed and likely said a quick prayer. (Although he never made a show of his faith, he had read through the entire New Testament during his final months of training for the run.) He would have stepped into his prosthesis the way another man steps into his jeans. He would have washed and dressed and stuffed his gear into his pack and then headed out to the parking lot where Doug and Darrell, Lou Fine, and the OPP trooper waited by their respective vehicles.

"If Terry said, 'Good morning, Lou, are you still fine?' then I knew he had slept well and we were in for a smooth ride," Lou had told me in Sudbury. "But if he just walked right past without a word, I knew that our morning was going to be interesting."

I turn left outside the motel and run past the 24-hour coffee shop, the dark Chinese restaurant, and the park by the mouth of Blind River. Terry's sea-to-shining-sea marathon appears possible at this hour. When he ran this stretch of road 26 years ago, it must have seemed a sure thing. He was 22 years old, and the cough and double vision had to be symptoms of the flu. He was more than halfway across Canada now, more than halfway home.

I had learned, however, that Terry rarely thought in such abstract terms. When he reached the streetlight, he thought about making it to the gas station. When he reached the station, he thought about running to the water tower on the edge of town.

But no matter how iron your discipline, sometimes your mind drifts. On this morning there are no dogs howling or monster semis batting past with a back draft that knocks you halfway across the highway. The fog lies softly over the muskeg in the last of the moonlight. The breeze is cool off Lake Huron, and the dawn light lacks the day's punishing glare.

Sometimes a farm family would be out at dawn to greet Terry and offer a doughnut or a cup of tea. But not today. It's just the OPP cruiser up front and Doug and Darrell in the van beside him and Lou in the RV, riding sweep. No sweaty crowds, no reporters asking why. The springs on his prosthesis make a steady mechanical squeak. Now the light is rising. A half mile up the highway, a granite outcropping takes shape out of the fog. Terry sets aim at the rock, emptying his mind, keeping his pace, moving west.

* * *

A memorial of Terry Fox erected outside of Thunder Bay on the Trans-Canada Highway. Photograph by Richard Keeling.

* * *

Shelly Skryba cried on the day Terry Fox died, June 10, 1981. It had been nearly 10 months since he had come through Wawa. She saw him leave town that evening, and then two weeks and 293 miles later–after running through cities like Thessalon and Marathon–he came to a spot on the highway a few miles east of Thunder Bay and stopped, brought to a halt by crushing chest pains. Three years earlier, when the surgeons had sawed off his leg at the hospital in British Columbia, Terry had convinced himself they had also cut out his cancer; he had willed himself inside that charmed circle of osteogenic sarcoma survivors, the 50 percent who were cured.

But it was now plain that, to his and the world's grief, he'd been running outside that circle all along. Before the amputation, seeds of carcinogenic bone had migrated to Terry's lungs, and had now bloomed into an inoperable secondary cancer. The Marathon of Hope was suspended in midstride. Terry was flown to a hospital not far from his home, where, after a 10-month decline, he died.

Since his death, the Terry Fox Foundation has continued to raise money for treatment-based cancer research chiefly through donations gathered at the Terry Fox Runs. Over the years, the foundation, led by Darrell Fox, has maintained tight control over Terry's name and brand and has shown the same kind of disciplined focus for fund-raising that Terry displayed. For instance, in 2000, Darrell turned down a request by the Canadian mint to sell a Terry Fox commemorative coin set marking the 20th anniversary of the Marathon of Hope; portions of the profits would have gone to the foundation. Only after the mint came forward with a new proposal in 2005–it would produce a general-circulation silver dollar embossed with Terry's image–did Darrell say yes. "Terry's original goal was to raise a dollar from every Canadian," Darrell had told me before I set out on my trip, "so the symbolism was perfect."

Like Shelly, much of Canada was in tears the day Terry was buried. The CBC televised the funeral live from Port Coquitlam. By that time, Terry was already half legend. There had been a telethon with Gordon Lightfoot and other stars. Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau made a speech. Millions of dollars had poured in from every province in Canada and around the world. Plans formed for the first Terry Fox Run that September.

After his funeral, the media stories about Terry worked down to a trickle. Life returned to normal in Wawa. The men punched in for their shifts at Algoma Ore, the big trucks boomed by on the Trans-Canada Highway. In the summer the fog drifted off the lake, and in the winter the iron cold clamped down. In September, just after the start of the school year, the kids ran around the playground in memory of Terry Fox.

Jason Bielas answers the phone guardedly. Why would a sportswriter be calling? But when Bielas, a 31-year-old postdoctoral fellow in the department of pathology at the University of Washington Medical School in Seattle, hears the name Terry Fox, he relaxes. Somehow, whenever Terry is involved, no connection is too far-fetched. There always seems to be a thread to follow.

So Bielas discusses his recent work. He is helping develop a reliable laboratory test for measuring the level of cancer-associated mutations in DNA. With an accurate mutation-level test, Bielas explains, thousands of unnecessary surgeries could be avoided each year. But Bielas also talks about his challenges: Federal funding to the lab has just about dried up. Only 10 percent or so of the NIH grants his department applied for this year in the United States have been approved. Which leads the conversation back to Terry. Because Bielas is the recipient of a $40,000 Terry Fox Foundation research grant, Bielas doesn't share his colleagues' anxieties. He can continue his work in the way he sees fit. This makes Bielas feel lucky, and somewhat guilty, and also, especially at this time of year, a little homesick for Canada. Each September, when he was growing up in Toronto, Bielas would do the Terry Fox Run at school. Of the 4,000 Terry Fox runs, only a few are held in the United States. When Bielas mentions Terry Fox to his American friends, he rarely gets more than a blank look in return.

* * *

In 1981, at the age of 17, Shelly married Earl Dereski, and they soon had two daughters. Shelly worked on being a mother for 10 years, then went to college and earned a nursing degree.

Life was fine except for one thing: Taylor, the couple's second child, was always sick. She was constantly missing school; she didn't have the same energy as other kids. Shelly took her to the doctor and they ran tests, but they couldn't find anything wrong. The pattern continued through the summer of 1998. Taylor was sick when she started high school in September, and by Halloween she was too weak to get out of bed. Shelly took her to the hospital in Wawa, but the doctors still couldn't find anything wrong. Taylor went home and collapsed into bed. In the middle of the night she was burning up with fever and her pulse was racing. Her mother put her in a cold tub. They got through the night, and at first light Shelly drove Taylor down to the emergency room. X-rays revealed a foggy mass in Taylor's left lung. The doctors diagnosed pneumonia and put her on antibiotics. But Taylor's condition worsened.

Over the next week, Taylor grew increasingly delirious. One night, Taylor lay quietly in bed, when she said to her mother, "I know why I'm sick."

Shelly didn't like this. "Why?"

&Shelly didnt like this. "Why?"

Shelly went cold. Her mother, Myrna, who had suffered from MS, had died before Taylor was born. Shelly hardly ever talked about her.

At the end of the week it was decided that Taylor should be seen by specialists in the Soo. There, doctors detected a tumor sitting at the opening of her left lung. The next day a medevac helicopter flew Taylor and her mother down to The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, one of the world's leading pediatric hospitals, which was popularly known by its nickname, Sick Kids. Specialists verified that the tumor was malignant and had gradually cut off the blood and oxygen supply to the organ. The lung had stagnated, collapsed, and filled with pus. The simmering infection was what had made Taylor sick all her life and was now threatening to kill her.

"At the time, I was too scared and worried to remember that secondary lung cancer was what killed Terry," Shelly would later tell me. "But at the same time, I couldn't help but think of him. Terry Fox was all over Sick Kids."

On a practical level, Terry's influence was tangible in the hospital's radiology and chemotherapy, its surgery and physical therapy: Over the last decade, these and other healing arts had dramatically advanced due to support from the Terry Fox Foundation.

But Terry was also present in other ways. His picture, for instance, looked out from the T-shirts of the young patients on the oncology floor. These kids had grown up with Terry Fox. They had listened to their parents tell stories about him around the dinner table, had studied him in the classroom, and had run in his memory on the playground. Now, as they engaged cancer themselves, Terry was their guide and companion.

* * *

Driving Highway 17, I approach Wawa seemingly by the inch. Bombing rain eclipses the Montreal River grade, and the CBC drifts out of range on the radio. The 18-wheelers throw up fiendish curtains of water. Over the last day or so behind the wheel, I've begun thinking out loud, but not exactly talking to myself. Terry, I complain, as, semi-blindly, I pass another truck on the rainswept highway, Advertisement - Continue Reading Below?

A hundred miles west of the Soo, I stop for gas, coffee, and to call ahead to Wawa on a pay phone; my cell phone doesn't work in Canada. I dial the race director of the annual Terry Fox Run in Wawa, but I'm doubtful she'll be home on a Saturday afternoon. I'm right; a young voice answers, her daughter's voice. Her mother and father are down in the Soo for the weekend, she says. She would normally be there, too, but on the spur of the moment she decided to drive up to Wawa for a fishing derby, which is currently suspended by rain. Purely by chance she had answered my call.

Motherhood Changed How She Approaches Running… magazine in the States, traveling through, thought I'd take a shot… the kid must think I'm a lunatic. But she hears me out calmly and says she'd be happy to talk with me. In fact, Taylor Dereski says, she has her own Terry story to tell.

On November 23, 1998, surgeons removed most of Taylor's lung, leaving a long, hook-shaped scar across her back. She returned home to Wawa, where she missed the remainder of her freshman year in high school. Taylor quickly caught up, however, and in ensuing years, short of some type of vigorous exercise, savored all the pleasures that her disease previously had denied her. She developed a passion for fishing. She graduated from high school and immediately settled on a profession. "Because of the model of my mother, I hope to become a nurse," Taylor says, sitting in her parents' apartment. "Due to my own experience with cancer," she adds, "I'd like to one day work with kids with cancer."

Taylor pauses. At 22, she is the same age that Terry was when he ran through Wawa, and radiates the same sense of life that jumps out from his photos. "My mother talked about Terry a lot, and we learned all about him in school," she continues. "I don't mean to sound spooky or cornball, but having gone through the same thing as he did, and with him actually visiting Wawa, I feel like I know him."

* * *

In September 2002, Shelly Dereski noticed that something had changed about her hometown. For the first time since 1981, Wawa lacked a Terry Fox Run. There had been no deliberate slight; people hadn't forgotten Terry. The run organizer had simply moved away, and nobody picked up the ball. Shelly was horrified.

"How could there not be a Terry Fox Run in Wawa?" she says. "With my daughter being a cancer survivor, I had a direct connection to him. And Terry ran through Wawa. I saw him."

So Shelly volunteered to become the town's Terry Fox Run director. She didn't know anything about the job. She called the run director in Thunder Bay to get advice and sent away to the Terry Fox Foundation for an organizer's kit. Soon Terry's photo appeared on the same bulletin boards and store windows where the original Terry Fox posters had hung during that golden month of August 1980, when millions of people followed each mile of his magical run through northern Ontario, step by syncopated step. Shelly was young then, and she dreamed of having a beautiful daughter someday. Something profound had touched this cold little town, delivered by a one-legged man who paused here during his long run home.

Shelly had Earl lay out a 5K course around the high school, while she organized a barbecue at the finish line, and a few hundred people came out, raising $2,600 for the Foundation. For the next few years the turnout grew, and in 2005, during the Marathon of Hope's 25th anniversary, townspeople contributed more than $5,000. Taylor's diminished lung capacity did not allow her to run or walk at the event, but one year, as a cancer survivor, she cut the ribbon at the starting line.

Her mother smiled. Terry Fox had returned to Wawa.

On the third Saturday in September, a month after my trip through Ontario, I drive north from my home in Portland through Washington State, under the Peace Arch border crossing, and into British Columbia. I spend the night at a motel in Port Coquitlam, just outside of Vancouver, watching the replay of a 2005 TV movie about Terry Fox and the Marathon of Hope. I'm impressed by the actor playing Doug Alward. The next morning I meet the real Doug Alward, a shy, intensely private man, and together we go to the Terry Fox Hometown Run in Port Coquitlam.

Near the starting line before the run, Alward shows me the various memories of Terry that have been gathered on a bulletin board. Noting Alward's interest, but having no idea who he is, a race volunteer asks him if he has any stories to share. Alward starts to speak, then catches himself, gives an awkward smile, and decides to walk away. I follow him.

At this same hour, in their respective time zones around the planet, Terry Fox Runs are rolling in hundreds of towns and cities, including Toronto, where I picked up Terry's trail, and Wawa, where for reasons beyond my ken, the trail always seemed to lead me. There are still a few minutes before the start, and to pass the time I ask Alward about his memories of Wawa.

"Everything about that day was a blur," he recalls. "I vaguely remember the big white letters etched into a hillside on the highway."

Doug explains that their start that morning had been delayed because a film crew wanted to get a shot of Terry running up the nearby Montreal River grade. At his habitual 5 a.m. starting time, however, Terry would have been climbing the hill in darkness. So they waited an hour so the crew could shoot in daylight. "At the end of the day we had to pay the price," Doug tells me. "After leaving Wawa, Terry still had to run another 90 minutes to reach his quota for the day."

At that moment the ribbon is cut at the starting line. Alward, a 2:45 marathoner at age 48, takes off into the morning drizzle. I chug along in the middle of the pack, connecting Alward's story with my own memories of the town, the lake, the highway, and summer's dwindling days.