Last August, tucked away in my cubicle, I streamed the women’s Olympic track and road events in secret, hiding from my employer. These games, to me, were a defining moment. Five decades after Kathrine Switzer was nearly thrown off the Boston Marathon race course, our female marathoners were throwing down in Rio.

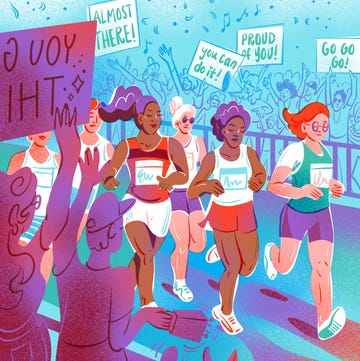

As I watched these women fly together in a pack, I thought about how empowering it must be to run in a race made only for women.

I knew that in recent years, women's running groups and races had made a comeback, coming into style as a way to bolster a sense of strength and togetherness in the female running community. Between this promise and the allure of female strength and speed in the Olympics, I decided I was going to sign up and race among my kind.

I started doing research. What I found—races with names like Divas, Princess, and Dirty Girl—felt, well, offensive.

As an athlete, I cringed at the crowns and stiletto heels in the logos. The “OMG YOU DID IT!!!” advertising. The hunky firemen posted at every mile mark.

RELATED: Running While Female

I couldn’t stand their assumption that every woman wants all-pink everything, that we’re pretty flowers who need extra rewards to simply run 13.1 miles straight.

Weren’t these no-boys-allowed races taking a step in the wrong direction? Weren’t they—dare I say—sexist?

The more I dug into this, the more I worried that instead of empowering women, women’s races were harming us by perpetuating the same stereotypes that limit us in the first place. But I knew that if I kept looking, I might find the women’s race for me—one that would promote women’s empowerment without downplaying my athletic goals.

So when I found the Naperville Women’s Half Marathon, a women’s race without the “tutus and tiaras” mentality, I signed up immediately.

On race morning, as I ran through Naperville’s picturesque streets, I admired the blooming lilacs, and in the first miles, amid all the adrenaline, I experienced moments where I closed my eyes, felt my arms swing in synchrony with my breath, and felt pure power coursing through my veins. It was like any other race.

But once I settled into my pace, I felt the sense of strength that all of the ads promised and was able to really examine the role sexism plays in running.

As I took water from the girls’ cross country teams, I thought about what those teenage girls might face while on the roads. Do they have to look over their shoulders during morning runs?

Would they have to run in a full shirt, in 95-degree heat, for fear that their bare stomachs might invite catty comments or sexual assault? Would they starve and overwork their bodies, sustain injuries, and sit out races just to meet the impossible physical standards that we only seem to impose on women? Would they too be forced to choose between skinny and strong?

As I scaled the hills at miles six, I wondered whether it was even possible to be a strong woman runner. We’re assumed to be weaker than men, yet we’re still expected to do everything-and make it look effortless. And when we address any of this, we’re accused of being “oversensitive.” Though I can’t speak for any woman except myself, it sometimes leaves me feeling as if my gender is another obstacle for me to overcome, like my piriformis injury that just. Won’t. Go. Away.

Flat and Fast Half Marathons Bobbi Gibb, of Kathrine Switzer, of all the other trailblazing women whose efforts gave us the gift of running. I thought of the women who were told, by doctors, that running more than a mile would leave them too exhausted to have babies. I thought of the 60-something-year-old women in the race field, who, pre-Title IX, weren’t allowed to join their school’s track team.

ALSO: Do Women-Only Races Still Have a Purpose?

And looking around, thinking about the thousands of women in the race field, and the girls cheering at the water station, I renewed my strength from all of the ordinary women who, every day, do extraordinary things.

That’s probably the real value of a women’s race. We don’t need to rely on giant spectacles to feel empowered. We showcase our strength every time we lace up our shoes.

But when our gender is so often framed as a “problem” or an “obstacle”, we do need opportunities to celebrate our womanhood.

Women's races offer that experience to every type of woman, from the first-timer seeking a comfortable introduction to racing, to the group of friends making it a girls’ weekend, to the competitive half marathoner racing for prize money, or all of the above.

Beyond simply accommodating women, they’re also addressing the barriers that still prevent some women from participating. For example, the Naperville Women’s Half will soon introduce a Maternity Mile for expecting mothers next year and several women’s triathlons also offer childcare options for current mothers.

And those gimmicks I so abhorrently objected to? I feel less inclined to dismiss them after seeing a gathering of women—some doused in glitter, some not.

Because “pink" and "athletic" aren't mutually exclusive. Putting a tutu around your waist doesn’t automatically prevent you from running a PR. And tiaras don’t magically suck the competitive impulses from your mind.

By assuming otherwise, I was automatically associating “feminine” things with weakness. I was limiting “all women” to my narrow standards of how a woman should run, how a woman should race, and how a woman should appear and behave...while accusing race directors of doing the same thing.

But it wasn’t until I rounded the final turn that I realized how powerful a women’s race can be. All around the chute, women of all shapes, races, sizes, and wardrobes basked in their accomplishments and better yet, supported each another.

And sure, no single girl power-y, glammed up race can make us associate women with strength to the same degree that we do for men. But every time that a woman sprints through a finish line, whether they’re rocking a tiara, checking their Garmin, or both, we move just a little closer to a solution.

Races - Places.